The long, long game

When it comes to ensuring a long-term and economically successful future for stadiums, diversity of use matters says Ben Martin, economist and analyst.

Within days of Germany taking home the 2014 FIFA World CupTM trophy, questions started raging about the future of the dozen shiny stadiums built and/or renovated for the 2014 World Cup. Observers speculated that at least four of the Brazilian venues will find it tough to fill seats and meet the massive upkeep costs. Already architects have produced intriguing images of the stadiums transformed into much-needed housing.

Brazil is certainly not alone in splashing out on host venues which, unfortunately, could have the potential to be ghost venues. Nevertheless, the development of stadiums for world sporting events, can and does, deliver multiple benefits — improved infrastructure, and elite facilities for national athletes as well as an enhanced national pride. Success is about making the most of these benefits for the long run.

After the crowds go home

When major events come to an end and the international fans go home, the spectator profile of the stadiums immediately changes from sports tourists to local residents. Operators or public bodies inherit the stadium and the reality of running costs hit public pockets. Unless occupation is transferred to an anchor tenant such as a local top-league football team, the prospect of high ongoing maintenance and utility costs is daunting.

The legacy optimum

In our work delivering stadium economic feasibility studies for world-event hosts, our first task is always to identify the optimum capacity in the legacy phase (reduced from world event staging). This is about taking a realistic view of potential demand throughout the year. This can be for a single sport (i.e. football) or a multi-sport facility. The concept is essentially the same. How can we make the stadium work economically? And what will make it, inherently, part of the local community? This will, in turn, make it part of the surrounding city, country or regional social and economic infrastructure.

In our work delivering stadium economic feasibility studies for world-event hosts, our first task is always to identify the optimum capacity in the legacy phase (reduced from world event staging). This is about taking a realistic view of potential demand throughout the year. This can be for a single sport (i.e. football) or a multi-sport facility. The concept is essentially the same. How can we make the stadium work economically? And what will make it, inherently, part of the local community? This will, in turn, make it part of the surrounding city, country or regional social and economic infrastructure.

Revenue sources

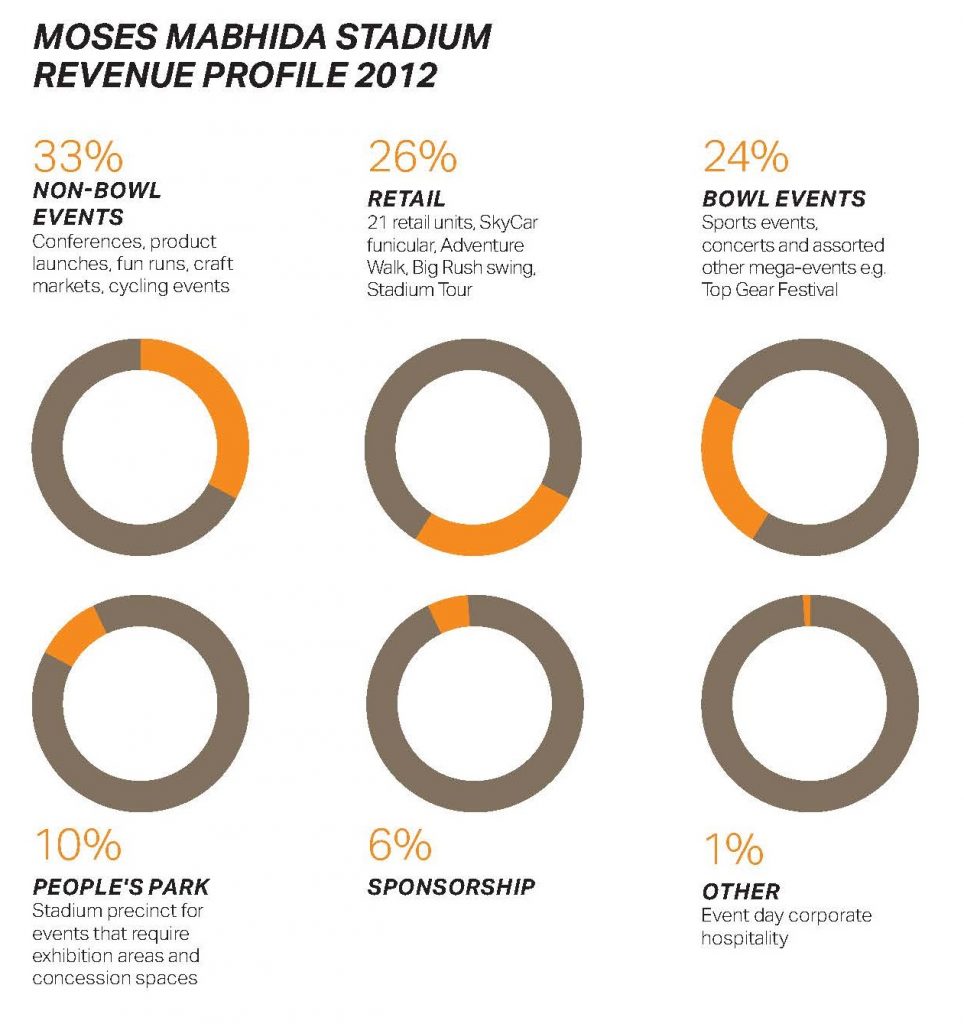

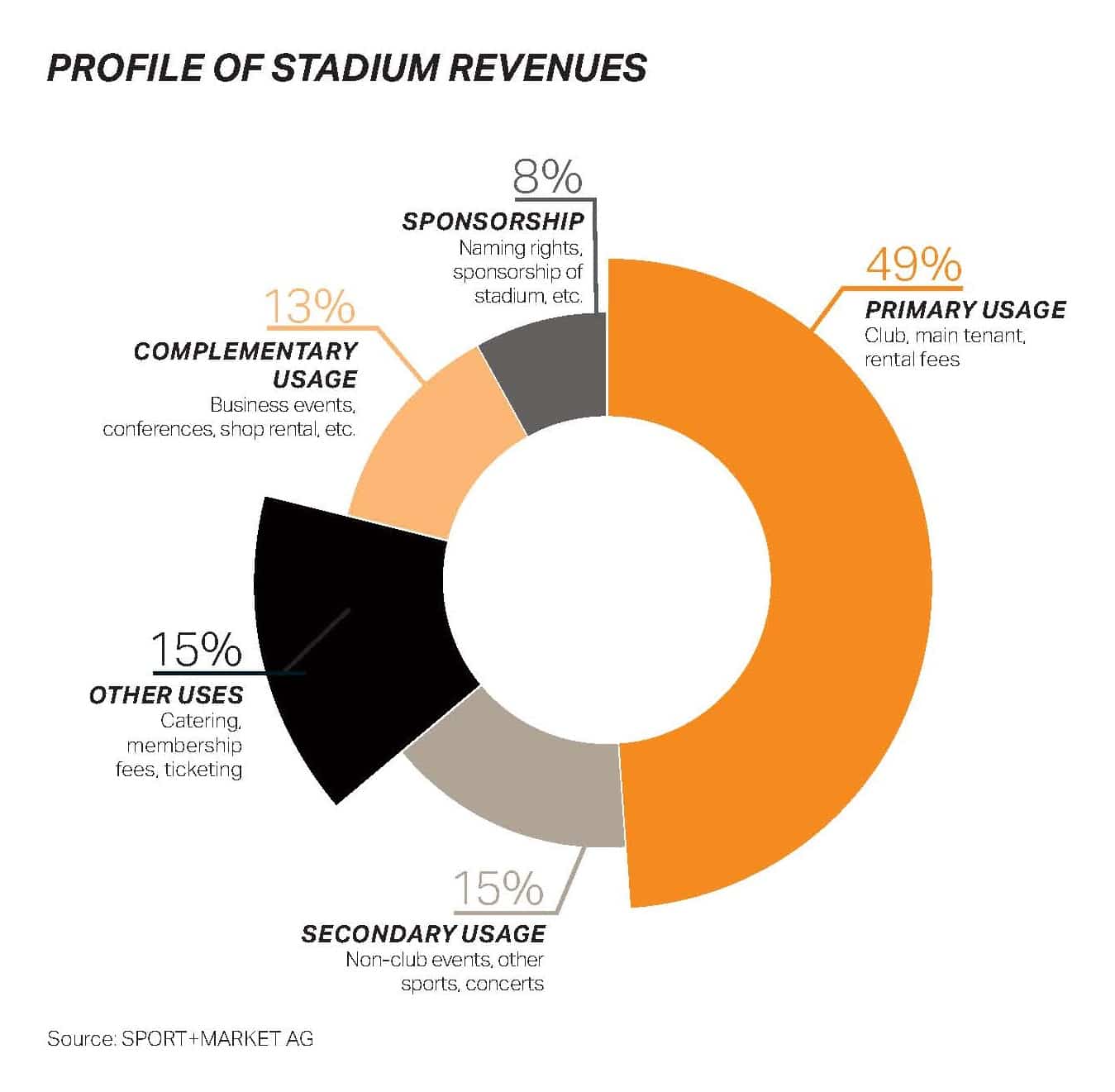

In a recent survey of 70 stadiums (located around the world) it was revealed that almost half of the stadium revenues come from primary usage. Additional income comes from secondary sources, such as non-club events, concerts, catering and venue hires.

This clearly outlines the opportunity and need for stadium operators to diversify their revenue streams. Without anchor tenants this can be tough, but is not impossible. For example, the Moses Mabhida Stadium in Durban, South Africa, a 56,000-seat stadium purpose-built for the 2010 FIFA World CupTM, is gradually reaching breakeven point. Without an anchor tenant, this has been achieved through innovative design that made the stadium a tourist attraction — with a SkyCar and Viewing Platform for unparalleled, 360 degree views of the city — and by hosting a variety of bowl and non-bowl events including the hugely successful Top Gear Festival.

Defining the commercial viability and use

If offering and designing for diverse use is invaluable to the long-term commercial viability of stadiums, we should also be, at the planning stage, considering the wider options of sporting facilities either as standalone venues or as part of a stadium complex development.

Arenas, for example, provide the opportunity for a mix of uses, all year round, encompassing major sporting events, music tours, venue hire and

corporate hospitality.

As standalone venues or as part of larger stadium complexes, the design and development of arenas becomes equally important. And their city-center locations link to the wider benefits of sport development: local pride, community engagement, health and wellbeing, and regular positive tourist income.

The First Direct Arena in Leeds, U.K., as Tele 2 in Stockholm, Sweden which opened in 2013 and includes entertainment space, and associated facilities which meet FIFA and UEFA requirements.

Whatever the ambitions for stadium and arena development, planning and designing with long-term commercial and community viability in mind will transform any investment. The inclusion of a diverse range of uses and activities that facilitate the venue operating non-stop throughout the year will have a significant positive impact on project cashflow and the scheme’s financial return profile.