How to future-proof water treatment plants: transitioning to a 50-year planning horizon

Traditional facility planning for water treatment facilities has typically focused on relatively short-term infrastructure needs based on updating demand projections, addressing compliance risks, and replacing aging assets. However, this approach is increasingly misaligned with the realities of a changing climate.

When readying treatment plants for the future, there is a risk of failing to properly or fully account for the long-term and compounding impacts of extreme weather, shifting rainfall patterns and rising temperatures on water quality and treatment needs. As a result, facility plans struggle to manage uncertainty and are often unresponsive to evolving stakeholder expectations. This not only limits solutions for resilience but also heightens financial and reputational risks for utilities.

How do we modernize water treatment facility planning?

Fortunately, there are models for what modern facility planning could look like across the globe. Facility planning for three North American water systems — including a Midwest user, Pacific Northwest user and Central Mountain user — demonstrates how a 50-year planning horizon, combined with a social value lens that considers broad internal and external stakeholder inputs, can modernize facility planning. This approach integrates climate resilience, stakeholder engagement and adaptive planning to provide water systems with the best chance to be ready for the future.

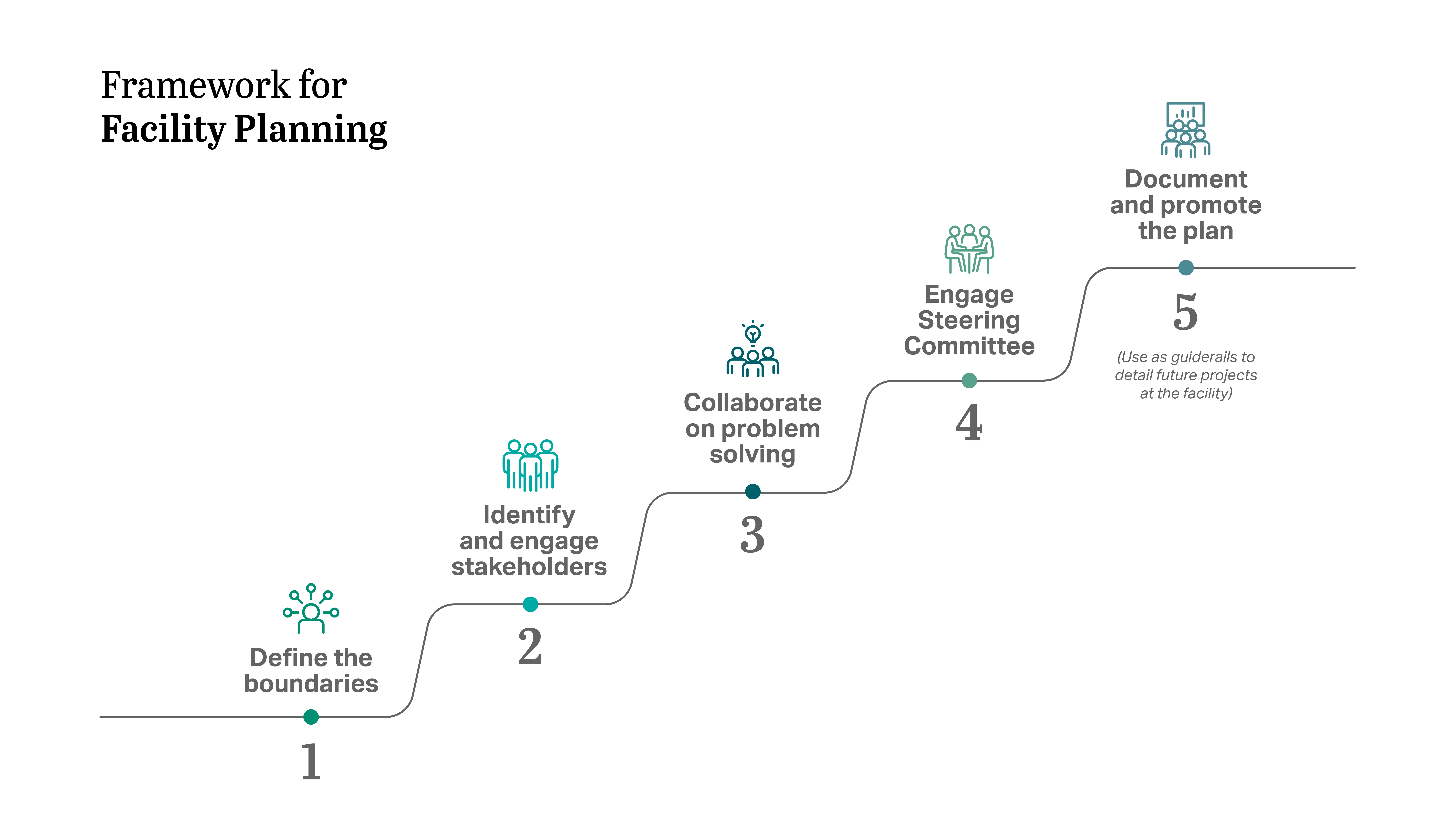

Five steps to modernize water treatment facility planning

We developed this framework through lessons learned from facility planning for the three North American water systems. All three faced conditions of increasing uncertainty, attributable to water quality, hydrology, population dynamics, industrial customers and/or changing attitudes to social value. Unsurprisingly, they also all faced their own unique set of challenges, from aging infrastructure to the need to augment and diversify the supply portfolio. Due to the different needs we saw in the three case studies, this framework is flexible by design.

Step 1: Define the boundaries

Begin with establishing the boundaries for the facility plan: in addition to the treatment works, should it include the supply and network infrastructure? Extend the planning horizon to 50 years to better align with long-term challenges and opportunities. As the plan is developed, integrate climate considerations — such as changes in hydrology, water quality and shifting water demand patterns including domestic climate migration — into the analysis. To anticipate a water system’s needs in the future, we first consider the magnitude of change that has come before us in terms of how we use water, how our cities have grown, workforce dynamics, and 50 years of technology and regulatory advancement. We then consider potential gaps in the existing treatment and supply portfolio, to provide multiple barriers for pathogen control and particulate removal, redundancy in the supplies, as well as different classes of contaminants.

Equally important is embedding social value into the planning process by addressing factors like water affordability, equitable access to safe drinking water and opportunities for local workforce development. This holistic approach improves the likelihood that the facility is more resilient to future climate impacts and is more responsive to the needs of the communities it serves.

Step 2: Identify and engage stakeholders

The purpose here is to identify the stakeholders that can influence the outcomes, promote the facility plan or represent the community’s values, with the goal of going beyond internal stakeholder engagement.

For the Midwest user, external stakeholders took a lead role in developing and shaping the facility plan through a range of forums:

- Meetings with community members that historically had not contributed to a major infrastructure project, including representatives from low-income households and youth groups.

- Major customers, including wholesale systems, the school board, the university and a watershed steward advocacy group, were invited to participate in the project’s steering committee.

Internal stakeholders should include members of operations and maintenance along with representation from the wastewater, distribution system and water resources departments to provide an integrated water management perspective. In the Midwest case study, these utility representatives joined the major customers on the project’s steering committee. An executive committee can provide key links to finance and administration departments, whose support is key to securing the budgets necessary for implementation of the facility plan.

Broad representation from both external and internal stakeholders will lead to more creative solutions while also promoting broad support for the facility plan.

Step 3: Collaborate on problem solving

In this step, the needs and boundaries of the facility plan are considered in the context of potential solutions that are framed holistically to leverage synergistic benefits. For our three water users, we used historical data reviews, scenario modelling and/or demonstration testing to assess the feasibility of potential solutions. In this step, engagement with operations and maintenance staff is invaluable when defining the needs of the facility plan, as well as the potential solutions.

For our work with the Central Mountain user, the water system identified multiple climate futures and evaluated potential solutions against changing conditions. For the Midwest user, stakeholder input reshaped both the treatment goals and the infrastructure priorities related to water security and the supply portfolio.

Step 4: Engage the steering committee

Engage the steering committee early in the planning process to provide strategic oversight, foster alignment and support decision making. Be sure to define the committee’s governance, so that all participants understand expectations and the influence of their contributions.

Step 5: Document and promote the plan

The facility plan can be used to document assumptions for risk, infrastructure investment, workforce development and/or financial support.

The governance of the facility plan should consider how it is updated and used when implementing individual projects identified in the facility plan. All three water users documented their plan through a report and easy-to-read executive summary, and some formally presented it to its Council or Board for approval.

Case Study: The Midwest water user’s inclusive planning model

The Midwest user’s facility plan is a model of modern utility planning. As a result of extensive stakeholder input with major customers and broad-based community engagement, including customers underrepresented in the past, the city redefined its treatment goals and expanded the boundaries of its facility plan to improve water security for its customers in the face of drought and contaminant threats. The facility plan includes indicators to trigger action for contaminants like PFAS and 1,4-dioxane, while prioritizing affordability and reliability. We will use this inclusive, forward-looking model that is heavily founded in engagement when working with other water systems.

The final case for modernizing water treatment facility planning

No matter where you are in the world, our water systems are facing water security challenges — some more than others — but the uncertainty and unpredictability exist. And to address these, we need to do things differently. This framework and approach demonstrate that a data-informed and stakeholder-shaped plan will give us the best chance at meeting the needs of the water system well into the future.