Increasing storage capacity is key to a resilient and renewable power network

Ireland requires a stable supply of renewable energy to power homes and offices in the future. Investment in a range of strategic assets – such as pumped-storage hydroelectricity – will help build this resilience, but only if policy and barriers to funding are addressed, say energy specialists David McKillen and Ian Gillies.

At first glance, the figures are promising. The island of Ireland is increasing the amount of electricity produced from renewable sources. In the case of Northern Ireland (NI), that figure was 49 per cent, while in the Republic of Ireland (ROI), renewable generation (predominantly wind, along with small amounts of hydro, bio energy, ocean energy) accounted for 43 per cent of all electricity consumed, thus exceeding the 2020 EU target of 40 per cent.

However, these statistics tell only part of the story. When we include transport and heat to assess overall energy use, the island of Ireland still has a long way to go to wean itself off fossil fuels. For example, a report into ROI energy use estimates that over 93 per cent of energy for heat still comes from fossil fuels. The report noted that this was the main reason that the ROI isn’t making enough progress on overall renewable energy targets set by the EU.

Both governments are seeking to address this gap in part by increasing the percentage of electricity from renewable sources to approximately 70 per cent by 2030. In the ROI for example, some 12GW of renewable energy capacity will be added, with a heavy reliance on wind power. The closure of peat and coal plants will accelerate the transition. Hitting these goals would ensure the island of Ireland is back on track to reach net zero by 2050, in line with the both EU and UK government targets. To support this ambition however, changes are needed to the range of strategic energy assets currently available.

The ROI may have the second highest share of wind generated electricity in the 28 EU countries, but wind power alone cannot decarbonise the electricity supply. Complementary methods such as pump storage hydroelectricity (PSH), which can overcome the intermittency and remoteness of many renewable sources, are needed but have been under-deployed to date. Moreover, government policy to attract investment has too often focused on short-term metrics, leading to shorter term solutions. Together these have created barriers to investment that need to be overcome.

The challenges

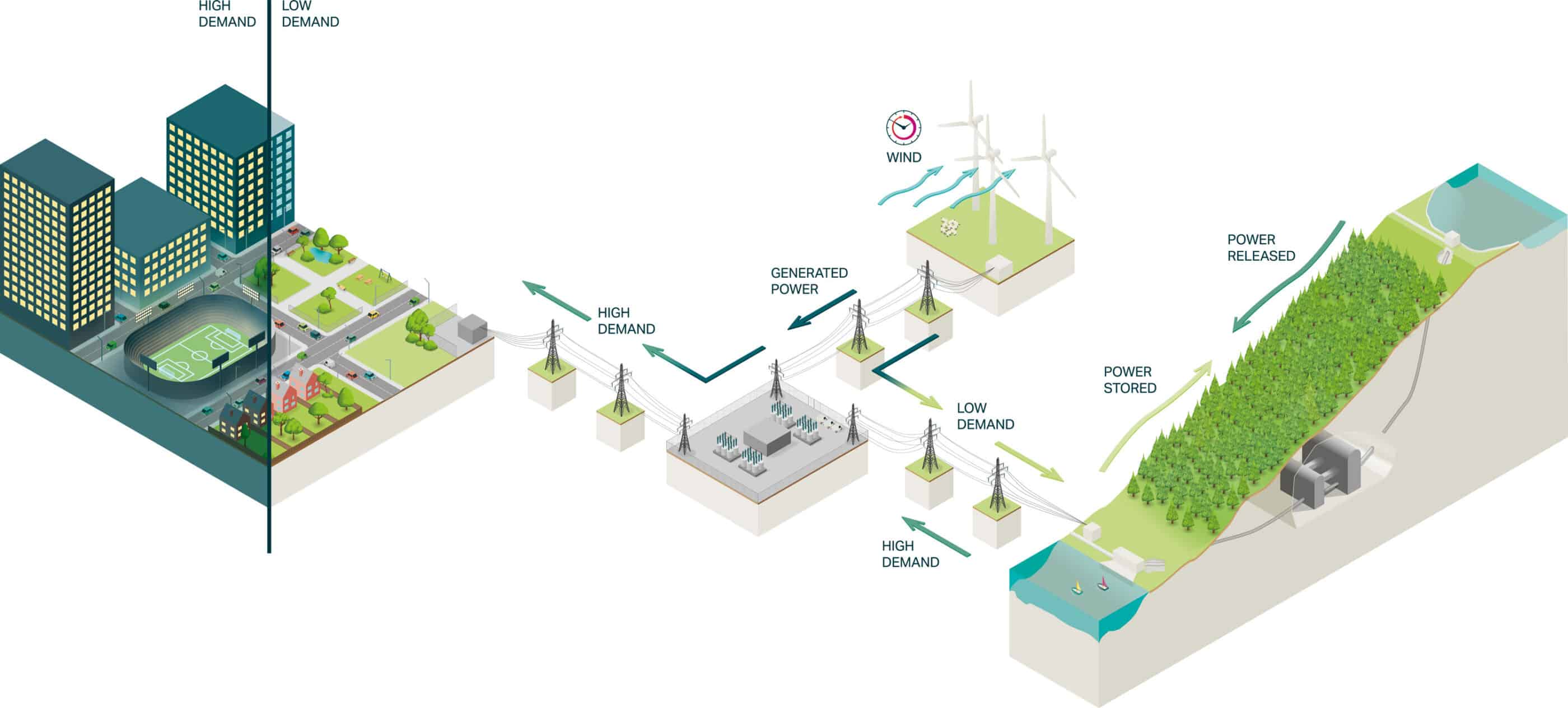

Renewable energy is not a panacea. First, generation is inherently intermittent – it is never always sunny or windy – so alternative power sources are needed to build reliability, and the storage of surplus power is vital to fill the gaps. Further, the geographic remoteness of renewable generation locations adds complexity to the management and control of power distribution.

Second, energy demand from a technology-hungry society is only increasing and the data centre industry, for example, is desperate to secure lower-carbon power. Such technology companies would prefer stable grid supplies to local backup generation. Moreover, to continue to attract foreign investment and companies to the island, there needs to be more reassurance around a secure – as well as green – energy supply.

Finally, other ways to tackle energy reliability have their shortcomings. As technology evolves, hydrogen fuel cells will likely be part of the mix, but they are still under commercial development and presently less efficient and more expensive than lithium-ion and other battery types, which have their own limitations due to short lifespan and current dependency on relatively rare metals.

The case for pump storage hydroelectricity

PSH is the only established technology that can store large quantities of energy. It helps tackle the issue of intermittency in renewable energy generation and can provide other grid stabilising services.

PSH generally works by using excess renewable electricity to drive water up to a high-level storage reservoir (see Figure 1). When either the wind stops blowing or the sun is not shining, water is released downhill, via a tunnel, to power the electricity turbines and substation, ensuring a stable, dependable flow of energy over multi-hour duration. Compared to other storage technologies, PSH is currently the only viable technology capable of true bulk storage at utility-scale; storing large amounts of energy over the course of multiple hours, sometimes days.

PSH also provides a broad range of other services that are extremely valuable to the grid. These include voltage regulation, frequency control through system inertia and short-term reserve, whereby more or less generation can be ordered for the grid, depending on short term fluctuations in supply and demand. Another plus is that these stations can store energy for long periods and convert it back to electricity in mere seconds.

In summary, PSH can enable the grid to offset thousands of tonnes of CO2 emissions a year and provide long-term energy security. No wonder the US Department of Energy’s Global Storage Database reported in November 2020 that PSH accounts for approximately 95 per cent of all official storage installations across the globe.

PSH is largely under-deployed in the UK and Ireland, though that situation is changing. There is only one active PSH scheme in Ireland: Turlough Hill, in the Wicklow Mountains, although we are currently assisting with the development of two further PSH projects across the island, and three in Scotland. One of these projects, Red John – a 450MW scheme on the shores of Loch Ness – has just been given the green light by the Scottish government.

A different investment framework

There are several reasons for the current lack of PSH facilities in Ireland. The privatisation of energy companies led to the so-called “dash for gas” in the 1990s. Gas initially appealed to investors because it was cheap, but its use for baseload electricity generation needs to reduce markedly in line with net-zero ambitions.

By comparison, a PSH facility, which may take up to six years to construct, requires significant capital investment – though it can eventually generate many millions in returns and last for over 70 years.

However, these excellent returns are hard to access due to current electricity market legislation and the funding framework for long-term developments of a strategic nature such as PSH. As things stand, UK government policy allows only for relatively short Capacity Market contracts for example, which means that revenue visibility and security over the asset lifespan is limited. PSH schemes take longer to pay back, though mechanisms – such as long-term cap-and-floor tariffs – are in place in other parts of the world to support longer-term investment of such critical strategic energy assets.

Policy change is by nature challenging but better funding support mechanisms must be established to deliver investment into the right technologies, including strategic storage for the medium and long-term future of the island of Ireland. Commenting on the Scottish Red John scheme, Michael Matheson, Cabinet Secretary for Net Zero, Energy and Transport echoed this sentiment, saying, “We continue to call on the UK government to take the urgent action required in reserved areas to provide investors with improved revenue certainty and unlock potentially significant investment in new pumped storage capacity in Scotland.”

There is precedence, however. Other strategic assets such as electrical interconnectors – physical links that allow electricity to flow across borders to the EU and Nordic electricity markets, sometimes via Great Britain – have been supported by a cap and floor regime. This is a combined approach that strikes a balance between commercial incentives and appropriate risk mitigation for project developers.

PSH is a valid, long duration, utility-scale storage solution that has enormous potential within a new all-island energy system. To facilitate implementation of these critical storage asset projects and technologies however, urgent policy changes need to be made at the highest level. Once in place, PSH can not only help the energy sector maximise its contribution to ROI and UK carbon reduction targets, but also increase grid resilience so that the island of Ireland remains attractive to the data centre and similar industries, so that foreign investment continues to flow in.