Empty building syndrome

Our offices are emptier than we think – and the latest figures from AECOM’s Time Utilisation Surveys show that organisations are still failing to reap the benefits of their investment in space.

AECOM developed the Time Utilisation Survey (TUS) for IBM in the early 1990s. It is now a tablet-based tool that enables us to gather data on how space in a building is occupied. Observations are made every hour during the core working day for two weeks. The data is recorded in our database in real time, building up a picture of how space is used each day. The results can easily be compared across different sectors and across geographies.

With over ten million observations from 500 offices in 27 countries in our database, we have drawn on the past decade of TUS information to reveal the latest on our empty offices.

Gross under-use

Our database reveals that workspaces (desks, offices and other types of workspace) are occupied on average 42 per cent of the time, and people are often away from their desks elsewhere in the building a further 18 per cent of the time. On average, therefore, 40 per cent – well over one-third – of workspaces are empty at any point during the core working day – and yet organisations are paying for this empty space.

While there is some variation across sectors and geographies, the general occupancy levels are consistent: workspace is grossly under-used.

On average, well over one-third of workspace is empty at any point during the core working day – and yet organisations are paying for the empty space.

All change

Increasingly, work is done outside the office. Yet, when people do come into their office, they no longer sit at the same desk all day. They need to talk, to collaborate, to concentrate, and to innovate. They need to be able to move quickly and easily between types of work and types of spaces.

Both of these trends indicate that the role of the office building is changing, providing an opportunity to unlock increases in innovation and productivity through the way we design and use our buildings.

These positive changes are rooted in flexibility and choice – creating work settings for different kinds of tasks and empowering people to decide when and where they work.

One way of achieving all of this is ‘agile working’ – breaking the connection between one person and one desk. The boost in productivity that results from the provision of a range of work settings, which allows for the alignment of workspace with how people actually work, can far exceed the initial cost of implementation.

There are two key challenges in making such a change. First, management needs to lead – significant cultural change is required to help people work differently, and the challenge is to change mindsets throughout the organisation. Senior staff need to see office space as a creative asset first, but conversations that should be focused on the relationship between the work environment and cultural change too often get side-tracked by a focus on short-term space savings rather than long-term value.

Typical daily activity pattern in workspaces based on one company example

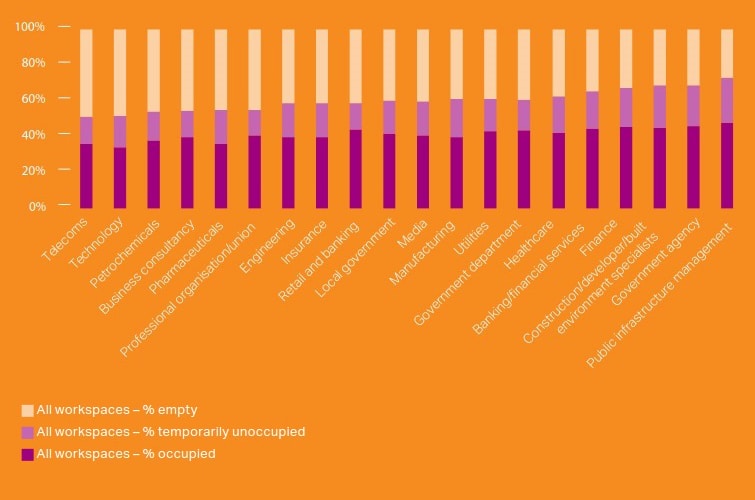

AECOM global occupancy database by sector (2004–2014 average)

This data shows a consistent picture of actual space utilisation across sectors. Our findings are that workspaces are only used around 42 per cent of the time.

A second important challenge in making this change lies with the development community. The industry needs to focus more on the purpose of the building and its use in the long term, rather than building speculatively without occupiers in mind. Real estate development is typically structured and rewarded on the basis of delivering a capital project where the keys are handed over with little long-term involvement in how the building performs for its users. In contrast, the most sustainable design solutions are developed when developers, designers, contractors and occupiers work together in partnership.

Stopgap solutions don’t address the issue

Organisations need to respond to these fundamental changes in the nature of work, and in the role of the office in the future. Instead of focusing on the gap between actual and potential space occupancy, occupiers need to focus on the gap between how people use the space in their office buildings and how they could use it to the best potential of the organisation – the behavioural and cultural gap.

Attention to this opens up exciting possibilities for combining the power of human resources, information technology, facilities management and real estate to release the true productivity of the organisation – its people and its brand – by aligning the workplace with how people actually work today.