Once and future creeks

Westerly Creek was restored from a runway in the Stapleton Airport redevelopment, Denver. Copyright AECOM photo by David Lloyd.

No matter what city you live in, there is a good chance that there is a buried creek right below your feet. Many people do not know that there was once a creek flowing near their home or business. As our cities developed, many of our natural creeks were placed in underground pipes and culverts for reasons that seemed sound in their day—create more developable land, make way for roadways, or even to bury a creek that was considered a health hazard due to poor environmental regulation and water quality. When I purchased my first home, a search over historic maps revealed that a small creek may have flowed near or even under my house. Today many communities are looking at the benefits of uncovering and restoring these forgotten waterways.

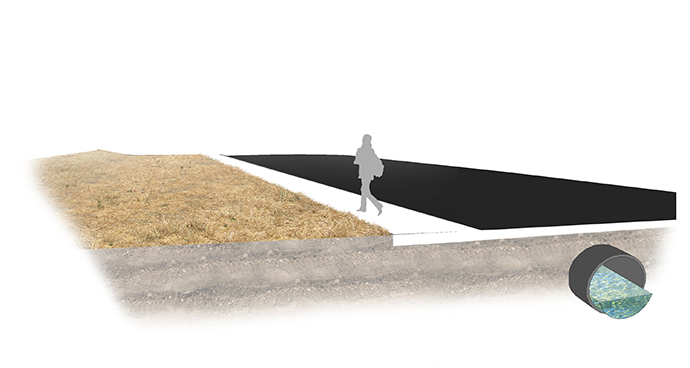

Aging infrastructure, flooding, and the desire for more livable cities is motivating communities to explore creek daylighting, which offers a unique opportunity to restore a historic waterway while also revitalizing the surrounding communities. Creek daylighting allows for the removal of undersized or failing pipes and their replacement with a surface channel that provides better flood protection along with additional environmental, social, and economic benefits.

Renderings by Hogan Edelberg and Blake Sanborn.

What this means to the average person is greater natural space in their neighborhood, better flood protection for their homes and businesses, and additional recreational opportunities through walking and biking trails.

Renderings by Hogan Edelberg and Blake Sanborn.

Over my career, I have worked on a number of creek daylighting projects and know that communities undertake these them for a variety of reasons. A recent project located along Lick Run in Cincinnati is designed to reduce over 600 million gallons of combined sewer overflow per year. Re-engineering this historic waterway is estimated to save the city over $200 million dollars by replacing the previously-planned underground storage tunnel. The creek project was determined to be less expensive and provide valuable community revitalization opportunities.

It’s engineering in reverse—instead of building large pipes to carry our creeks, we are building creeks to eliminate the need for large pipes.

I’m currently working on a creek daylighting project in San Francisco along the historic Yosemite Creek. As part of their 20-year, multi-billion dollar Sewer System Improvement Program, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission is planning to uncover and restore a half-mile of Yosemite Creek. This project will demonstrate that creek daylighting is not only a cost-effective tool to reduce combined sewer discharges to the San Francisco Bay, but can also provide valuable community amenities such as habitat creation, recreation, and education.

Renderings by Hogan Edelberg and Blake Sanborn.

San Francisco’s high-density urban landscape coupled with sky-high property values creates a unique set of challenges for engineers and designers. With a creek collecting stormwater from 110 acres of a local park, the team is relying on streetscape right-of-ways, city-owned parks, and innovative design responses. It will be exciting to see this project unfold in its complex context, and we hope it can serve as a model, along the Cincinnati project, for other cities across the country.

Renderings by Hogan Edelberg and Blake Sanborn.

Kerry Rubin (kerry.rubin@aecom.com) is an ecological engineer in AECOM’s Design + Planning practice.