Just 5 years to 2030: quick, cost-effective ways to cut energy use in buildings

Organisations committed to 2030 net zero targets have just five years to decarbonise their buildings. Many have rightly developed net zero plans focused on plant replacement. But that’s only part of the picture. The quickest, most cost-effective gains come from improving how buildings are run, write sustainability experts Miriam Ozanne and Dave Cheshire.

For those organisations committed to cutting carbon emissions in their buildings by 2030, the five-year countdown to net zero has begun.

Our building performance team is helping clients achieve operational energy savings of nearly 20 per cent in many of the buildings they’ve assessed without requiring any capital cost expenditure. Here’s how.

The case for prioritising building performance optimisation

Commercial buildings have become increasingly complex and difficult to control and manage. New technologies, shifting work patterns and rising climate pressures have all added to the challenge for asset and building managers. Many organisations have developed net zero carbon route maps for their portfolios that phase out gas systems and replace inefficient plant. This long-term planning is essential to avoid unnecessary investment in new equipment that will require a further future upgrade.

However, whether a building is still running on gas or has already switched to heat pumps, untapped opportunities to reduce energy use can frequently be found.

Yet, with day-to-day operations focused on keeping systems functioning and maintaining comfort for occupants, building performance optimisation is often not the priority. Nevertheless, investigating and cutting demand remains one of the most effective — and immediate — ways to reduce energy use, carbon emissions and operating costs.

It can even avoid unnecessary and expensive upgrades to plant and equipment or electricity infrastructure as replacement low-carbon technology such as heat pumps can be sized to meet smaller demands, saving both capital cost and embodied carbon. There’s a practical case too: operators are used to managing boilers and chillers. Replacing them with heat pumps requires them to learn how to control and fine-tune a different technology.

Seven quick, cost-effective ways to reduce energy use

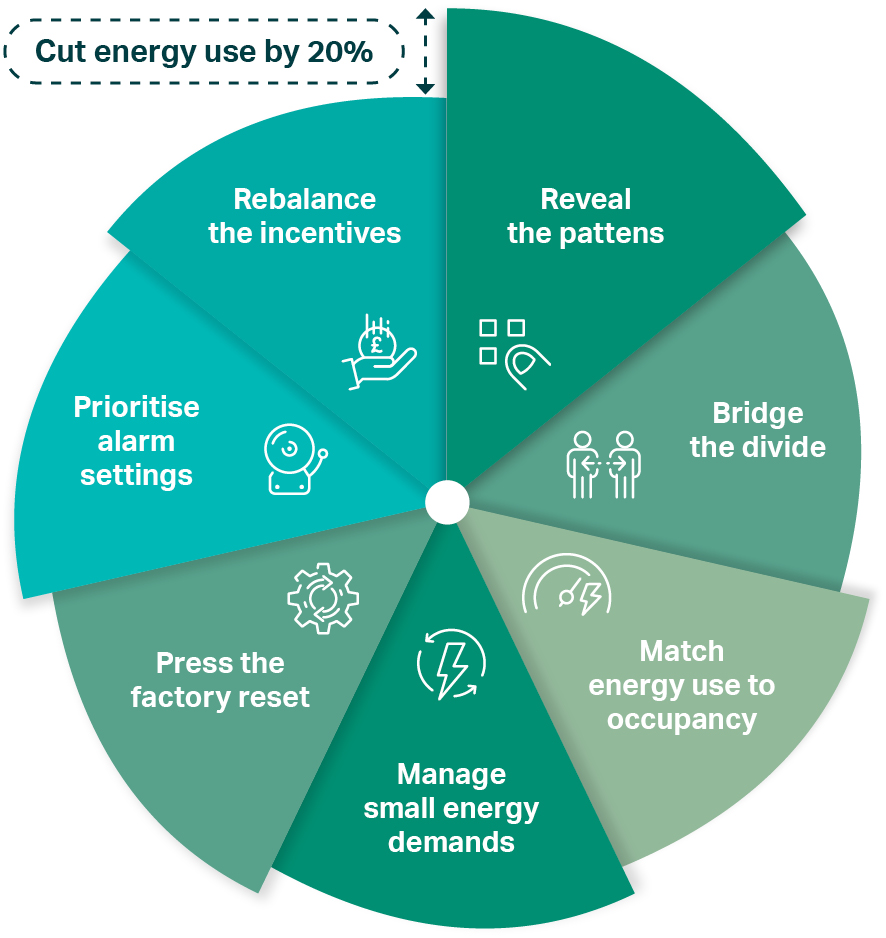

Across the buildings we’ve assessed, our team has encountered several recurring issues that push up energy use in buildings. We’ve outlined seven of the most common below, along with recommendations to address them, offering a clear, practical place to start (see Figure 1).

Taken together, these measures can cut annual energy use by up to 20 per cent, based on measured performance before and after changes were made.

For instance, we recently identified some key energy inefficiencies at London’s 20 Fenchurch Street (popularly known as the “Walkie Talkie”). Counter measures resulted in a 10.6 per cent reduction in gas consumption and a 5.3 per cent reduction in electricity use in 2023 — even as occupancy rose by more than a third over the same period (see case study below).

1/ Reveal the pattens in the data

One issue we often encounter is a lack of usable energy data. In many buildings, sub-meters aren’t working, or the data is not readily accessible to the building operators in a digestible way. Yet this performance data is essential — it helps teams understand where energy is being used and identify opportunities for savings.

Looking closely at energy data — especially half-hourly demand profiles — can reveal a lot more than just total use. It can identify maintenance issues, unexpected out-of-hours use, and other issues that might otherwise be missed.

We address this by analysing sub-metering data in detail and producing simple dashboards that compare design predictions for each system (lighting, heating, cooling, ventilation, etc.) with actual performance. This provides rapid feedback on any areas of out-of-range energy use that can be investigated and cut.

2/ Bridge the divide between landlord and tenants

The landlord–tenant split is a common barrier to cutting energy use and carbon emissions. From the landlord’s perspective, tenant spaces are often a ‘black box’, with no visibility over what’s been installed or how it’s being used. Server rooms or inefficient lighting may operate continuously without oversight.

At the same time, tenants typically have no access to energy performance data or the building management system (BMS) and may be charged a flat rate regardless of how much energy they consume.

We’ve found performance improves significantly when landlords and tenants work together — sharing data, agreeing temperature setpoints, setting clear rules for equipment installations and negotiating when systems are switched off.

3/ Match energy use to occupancy

With changing work patterns, office occupancy has become increasingly unpredictable. Many offices are nearly empty on Fridays or have large areas that remain unused for extended periods. Yet systems often continue to operate as though the building is fully occupied, wasting significant amounts of energy.

This makes it essential to have demand-controlled systems that ramp down based on occupancy and good zone controls so unoccupied spaces can be shut down. Careful monitoring of energy use compared to occupancy patterns will show where spaces are serviced when not occupied.

4/ Manage small energy demands

Small demands in a building can trigger large systems to run unnecessarily, driving up energy use. For example, a small demand for hot water for handwashing may kick in the heating plant or one tenant may ask for extended hours that keeps the whole building running later.

Dealing with extended hours can often be solved through negotiation and collaboration with the tenants. It’s becoming more common for landlords to put in place systems where extended hours have to be requested and become exceptions rather than the rule. It may even be possible to turn off the main air conditioning plant if the late occupancy is only for a few people. Small demands can be addressed by adding local plant and equipment, such as point-of-use heaters.

5/ Press the factory reset

Temperature setpoints and control settings often wander from the original design through frequent adjustments by different people — usually in response to complaints. This can lead to equipment not running at its optimum efficiency, with plant cycling on and off, or even heating and cooling the same space at the same time.

This can be solved by resetting everything to the original design settings and then re-calculating the optimum setpoints and adjusting accordingly. Access to the BMS should be restricted, with all changes logged. Occupant controls can even be set to reset to a default temperature after a set period, or overnight, helping to maintain stable, efficient operation.

6/ Prioritise alarm settings

Many BMSs generate alarms that are for routine plant operation. This overwhelms building operators and makes it difficult to spot genuine issues that need attention.

To improve efficiency, alarms need to be reviewed, categorised and prioritised so that only meaningful alerts are raised. This allows operators to focus on resolving real problems quickly, rather than sifting through unnecessary notifications.

7/ Rebalance the incentives

Reducing energy demand requires ongoing attention, time and effort, as well as diplomacy skills to negotiate with the many demands of occupants. Yet building operators are rarely incentivised to focus on efficiency. Most are tied up in the day-to-day demands of running the building and responding to complaints.

To shift this, giving operators the tools and incentives they need will help them to prioritise efficiency and help drive down energy usage.

Walking the talk: optimising the building performance of a London landmark

When our building performance team first partnered with the building management team at London’s 20 Fenchurch Street (popularly known as the “Walkie Talkie”), it was clear this wasn’t going to be a typical energy audit.

Our team was appointed to help reduce the building’s operational energy consumption and plan the route to net zero.

Usually, when analysing the performance of buildings in use, the challenge lies in limited data. Here it was the opposite, with more than 12 million data points from 700 submeters. A goldmine of information — but only if interpreted effectively.

We developed a bespoke tool to efficiently sort and sanitise the data, enabling our specialists to conduct a detailed analysis of energy use by equipment and area, observe 30-minute interval patterns and identify peak and baseline loads. By comparing these against expected values, we revealed several significant opportunities to improve performance.

Despite regular plant reviews already in place, we identified further inefficiencies — including equipment running out of hours and variable speed controls not responding as intended to, based on our understanding of building loads and external conditions. This also led to further savings opportunities.

Many of these measures have now been implemented, alongside other initiatives by the building management team, without requiring any investment in capital expenses. This contributed to a 10.6 per cent reduction in gas consumption and a 5.3 per cent reduction in electricity use in 2023 — even as occupancy rose by more than a third over the same period.

We are currently updating the net zero plan for the building and analysis of the latest metering data reveals significant further energy reductions have been achieved.