Are you prepared for the new Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard?

A definitive, industry-recognised standard is desperately needed to provide consensus, consistency and credibility on net zero buildings. This year, a new net zero carbon buildings standard (NZCBS) will launch that does exactly that. But what will it entail? And what do built environment professionals need to know? Sustainability director David Cheshire shares his thoughts ahead of its imminent release.

In the past decade, major developers, companies and construction clients have made public commitments to delivering and operating net zero carbon buildings by, or around, 2030. However, at present there is no single agreed definition of what constitutes net zero. This means that many buildings are being badged as net zero based on different standards and targets.

While the guidelines outlined in initiatives such as the Riba 2030 Challenge, the UK-GBC framework, the NABERS UK star ratings and the Low Energy Transformation Initiative (LETI) – as well as the CRREM Global Decarbonisation Pathways and Science-Based Targets for existing buildings – offer good starting points, each has different scopes, targets and levels of adoption.

A definitive, industry-recognised standard that unifies all these initiatives while providing consensus, consistency and credibility, is therefore desperately needed. Thankfully, a new net zero carbon buildings standard (NZCBS) is now being developed that does exactly that.

What is the Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard?

The development of the NZCBS is an industry-wide collaborative effort, involving major property-related organisations such as BBP, BRE, the Carbon Trust, CIBSE, IStructE, LETI, RIBA, RICS, and UK-GBC.

The voluntary standard will provide a clear definition of net zero as well as robust targets for all new building projects. Once released, the NZCBS is likely to become a single reference point for any developer wishing to demonstrate that their development or building has achieved net zero carbon.

To assess this, the key metrics specified in the standard include an operational energy demand (kWh/m2/year) target (the energy needed to run buildings) and an embodied carbon (kgCO2e/m2) target (the sum of the energy used to create the building).

When will the NZCBS be released?

The standard is due to be released in early 2024. Recently published results from the technical consultation – involving more than 500 individuals and organisations – reveal the evidence base collected so far.

The consultation reports propose preliminary targets for operational energy performance and the data ranges for embodied carbon for different building types.

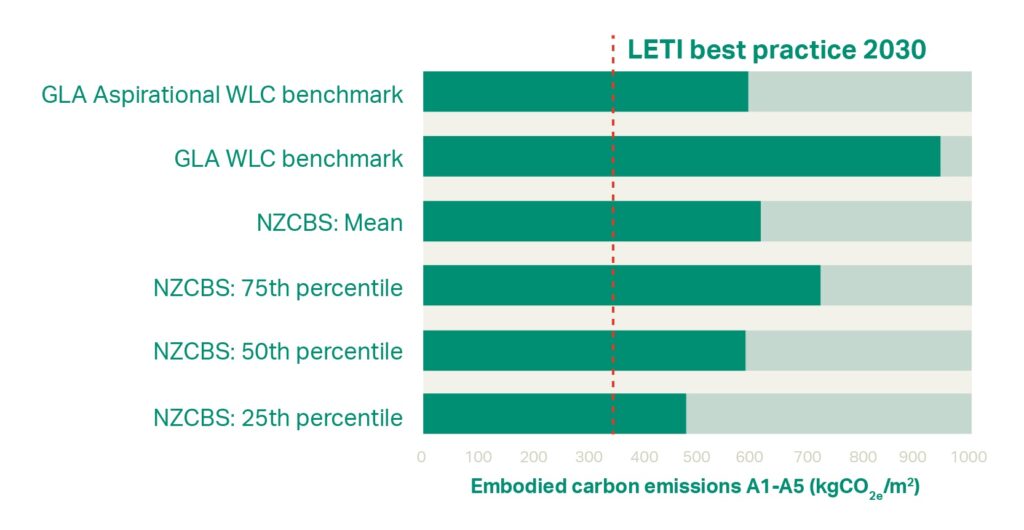

For example, Figure 1 (below) shows the analysis of the data received so far for office buildings, compared to the existing Greater London Authority (GLA) and LETI benchmarks. The working group has not yet proposed an embodied carbon target and has requested more data.

The chart illustrates that the NZCBS mean value aligns closely with the GLA Aspiration WLC benchmark, and that the LETI best practice target (the red line) is more challenging than even the 25th percentile figures from the data received to date. This demonstrates that a considerable shift is required to achieve the LETI target.

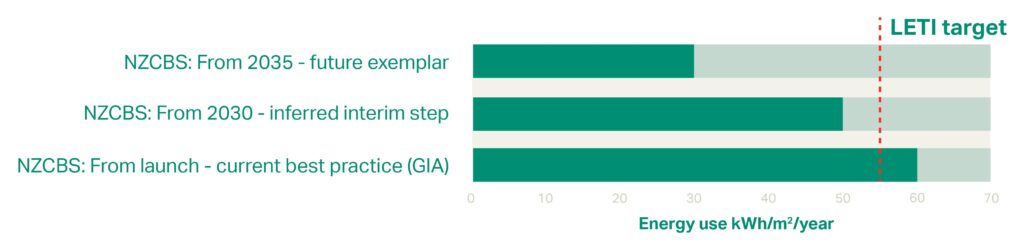

Figure 2 shows the initial proposals for operational energy targets (again for offices), based on the analysis of the data that has been received. These are initial results, but they show the broad direction of travel.

The graph displays the proposed performance levels from launch, for 2030 and for a future exemplar from 2035. The proposed NZCBS performance levels compare well with LETI best practice – with the future exemplar being considerably more challenging than the LETI target.

Reshaping the future for the UK’s built environment

Establishing an industry-recognised standard that sets out clear benchmarks for achieving net zero is crucial for ensuring that buildings achieve the performance required. Thanks to the commitment of the hundreds of volunteers and organisations involved in creating the NZCBS, the new standard is expected to accelerate industry progress towards decarbonisation and ensure alignment with the UK’s wider climate goals.

The targets will be challenging, demanding a radical departure from traditional practices and a fundamental shift in both the construction and operation of new and existing buildings. However, with the looming climate crisis, there is no alternative.

What might built environment professionals expect from the NZCBS?

To see how the NZCBS might work in practice, we can refer to two trailblazing standards that are already leading the way – namely the NHS Net Zero Carbon Building Standard and the Scottish Net Zero Public Sector Buildings Standard. The former is being applied to new hospital and healthcare buildings, while the latter is a voluntary standard currently used for the procurement of new public sector buildings being built in Scotland.

Both these standards provide insights into what built environment professionals might expect from the NZCBS once it is released. We have outlined some of these below to demonstrate what a net zero carbon standard needs to incorporate to be truly impactful:

Absolute, ambitious targets

Absolute (rather than relative) targets should be set for both operational energy demand and embodied carbon and these should form part of the project brief. Furthermore, targets need to be challenging and ambitious based on the science and a top-down approach of what must be achieved nationally and globally.

LETI led the way in advocating absolute targets with its seminal Climate Emergency Design Guide. This guide proposed absolute targets (e.g., 55 kWh/m2/year) based on a top-down analysis of the maximum energy demand of the built environment stock in the UK.

Prior to LETI, most net zero targets in the UK were based on a relative percentage reduction. Relative targets were set accordingly that made allowance for the proposed building geometry and servicing strategy. This allowed for more lenient targets to be set for complex buildings, compared to those with simpler built forms.

By contrast, absolute targets – which are required by both the NHS standard and the Scottish standard – set the same figure regardless of built form and servicing strategy.

The CRREM and science-based targets are also based on what the sector must achieve to keep within the carbon emission limits that have been set internationally.

Performance targets

Performance targets should be in place for specific elements which act as ‘backstops’ with associated guidance on how they might be achieved.

The NHS standard includes energy efficiency targets (for example, for u-values and g-values) to review a design against. These do not have to be obligatory targets. Instead, they can be a potential route to compliance showing how the overall target can be achieved, as well as providing a template to check against.

The targets can also help with early-stage design advice in the absence of sufficient information to do realistic modelling.

Net zero carbon coordinator

As with the NHS standard and the Scottish standard, a net zero carbon coordinator may need to be appointed to manage the delivery of the targets as well as challenge and advise the team.

For example, the NHS standard includes a design management tool that asks a series of questions which can be used to help structure the workshops and prompt investigations into ways that the performance could be improved.

Reviews at gateways

The performance of the design must be reviewed against the targets at key decision gateways and be part of the evaluation of whether the project can proceed to the next stage.

The NHS standard requires the embodied carbon and operational energy reporting tools to be completed at both Outline Business Case and Full Business Case stages in a project, which are key gateways to obtaining project funding and approval.

Similarly, the Scottish standard includes gateway reviews and provides guidance on model contract clauses etc., that help to embed the requirements into the project.

Actual performance

The operational energy targets must be based on an estimate of actual performance in operation, not on modelling estimates. They must encompass all the energy uses in the building, including the small power loads, not just the base build plant and equipment.

The project performance should then be judged on actual data. The Scottish standard contains requirements to write a measurement and verification plan to ensure that the correct metering and sub-metering strategies are in place – both of which allow the data to be accurately recorded. This is critical as many buildings do not have good breakdowns of energy data recorded, despite the best efforts of all.

For the embodied carbon targets, this means obtaining the as-built information from the Environmental Product Declarations and other materials quantities used in the project.

Third-party validation

It is invaluable for any standard to have some form of peer review to validate the modelling and actual performance results at key stages, such as the design stage, the completion of the project (for embodied), and after a year of operation, for energy performance.

The Scottish standard, for example, requires third-party reviews. This follows the lead of other standards such as BREEAM, Passivhaus and the newly introduced NABERS UK.