Visualising what we need to do to meet net zero carbon targets in buildings

Developers, operators and occupiers must work together in a radically different way to create and run net zero carbon commercial buildings. The net zero carbon quadrant is a simple way to visualise the holistic approach needed, says sustainability expert Dave Cheshire.

Reducing operational emissions is now only half the story when it comes to designing net zero carbon buildings. Thanks to the focus on operational energy demand and the radical decarbonisation of the electricity grid in the UK, carbon emissions of new buildings are decreasing and are projected to decrease further. This has raised the prominence of embodied carbon – the emissions from pouring concrete and forging steel – to a point where they are responsible for over half the total carbon emissions of a new building.

It’s amazing to think that the amount of carbon emitted is the same during the first two years of construction as 60 years of use. It comes as no surprise that the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) told the BBC that we should “refurbish old buildings rather than scrap them”.

However, the industry is still catching up with the change in emphasis towards embodied carbon and opportunities to cut carbon emissions associated with construction. Policy has started to shift, however. The London Plan asks for Whole Life Carbon Assessment for referable projects and LETI and RIBA are proposing stringent targets to drive change.

If we look at the LETI and RIBA targets, then the extent of the net zero challenge becomes clear. A highly efficient non-domestic building operates at around 120kWh/m2/year energy demand and the LETI / RIBA target is less than 55 kWh/m2/year. Similarly, a typical steel and concrete building comprises over 1,000 kgCO2/m2 and LETI / RIBA is proposing targets of <350 by 2030, equivalent to a 65 per cent reduction over the baseline.

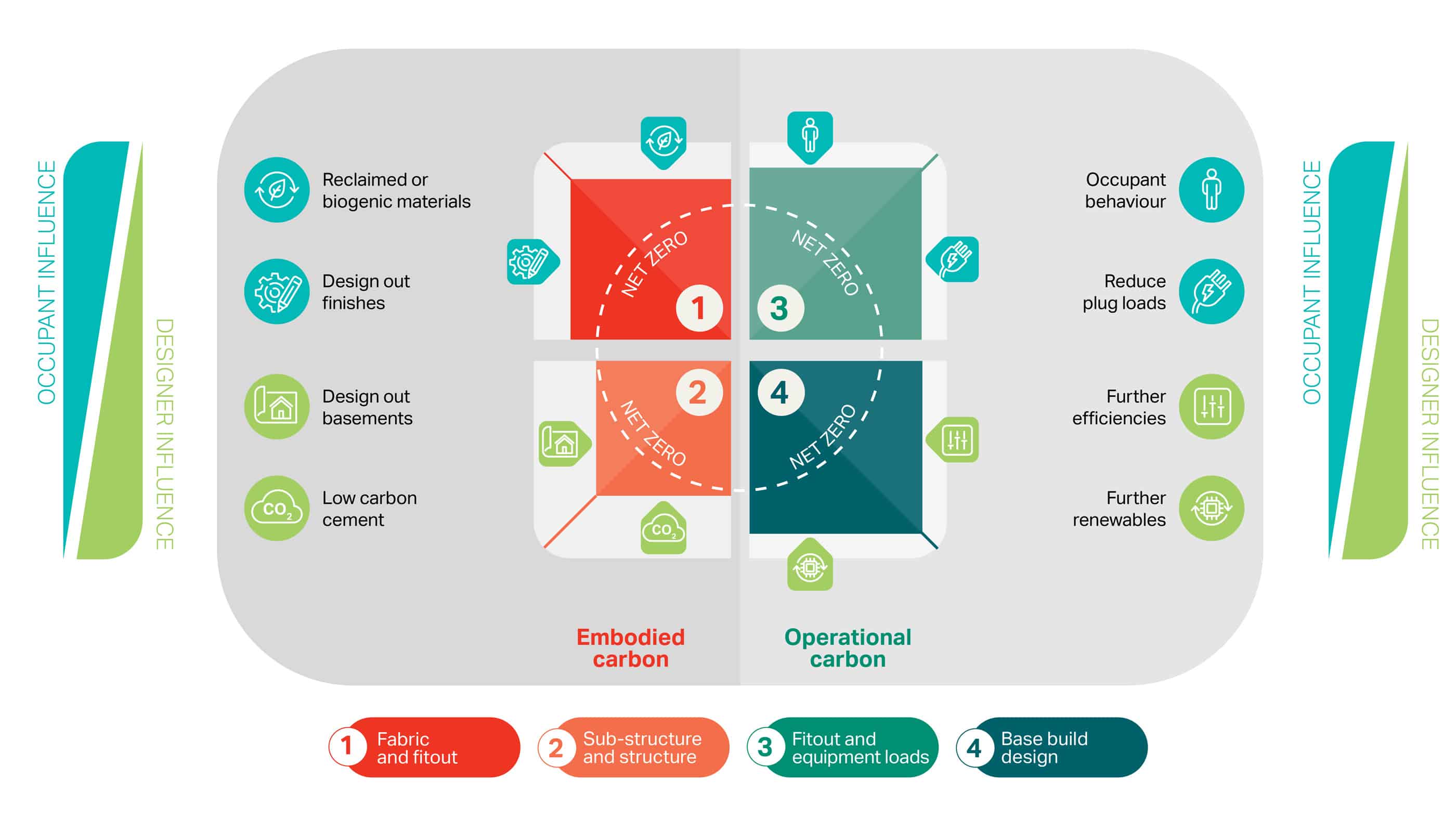

This article uses a simple visualisation to illustrate what’s needed to get our buildings to net zero. The net zero quadrant shows, in stages, the opportunities and influences over operational and embodied carbon reduction, but ultimately, demonstrates how net zero carbon can only be achieved if all parties – developers, operators, and occupiers – take a holistic approach to the way buildings are designed and operated.

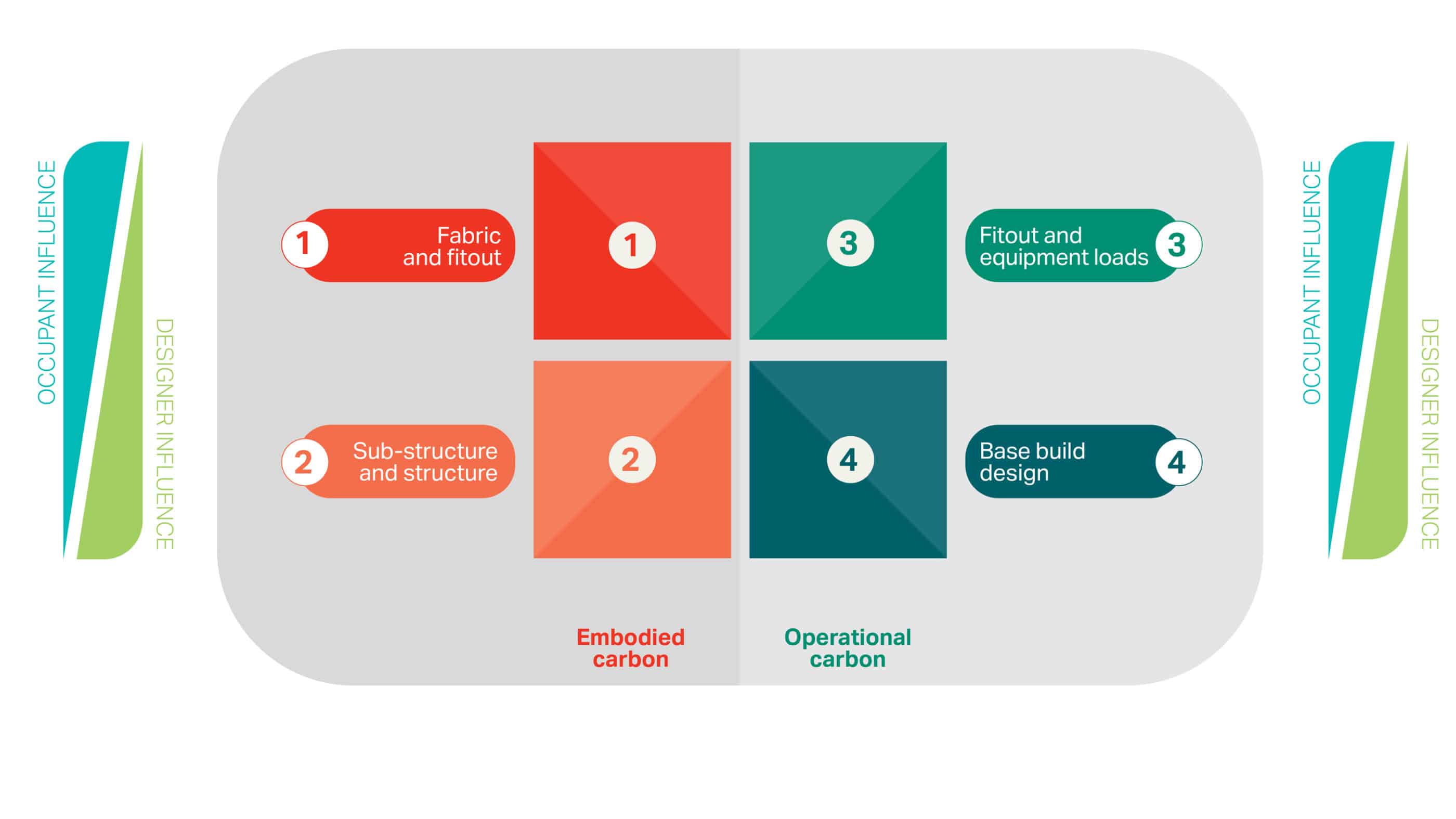

Dividing up operational and embodied carbon emissions

Roughly speaking, the proportions of carbon emissions from a new building can be divided into four segments (see Figure 1). This is a huge simplification and uses lots of assumptions, but it helps to illustrate the relative influence and the opportunities for reduction. On the left in yellow, embodied carbon is split into two blocks: substructure and structure, and fabric and fitout. On the right in blue, operational energy is split into the (regulated) base build loads and the (unregulated) fitout and equipment loads, which comprise the remaining operational carbon used.

Furthermore, the diagram shows how designers have more influence on the carbon content of base build while the clients or occupants have more influence over the carbon content of the interior fitout and the operational energy demands from equipment such as ICT.

Of course, the overall carbon impact of the building starts with the genesis of the project and the all-important project brief. As there has been so little focus on embodied carbon until very recently, there are more opportunities to reduce this element through changes to the design (and the brief!) that have not yet been taken. On the other hand, the operational energy and carbon emissions of new buildings are getting increasingly harder to reduce. This is because new buildings are designed to be highly efficient, usually through the adoption of a fabric-first approach, all-electric supply with heat pumps, and maxed-out on-site renewables.

Using the quadrant to show emissions reduction potential

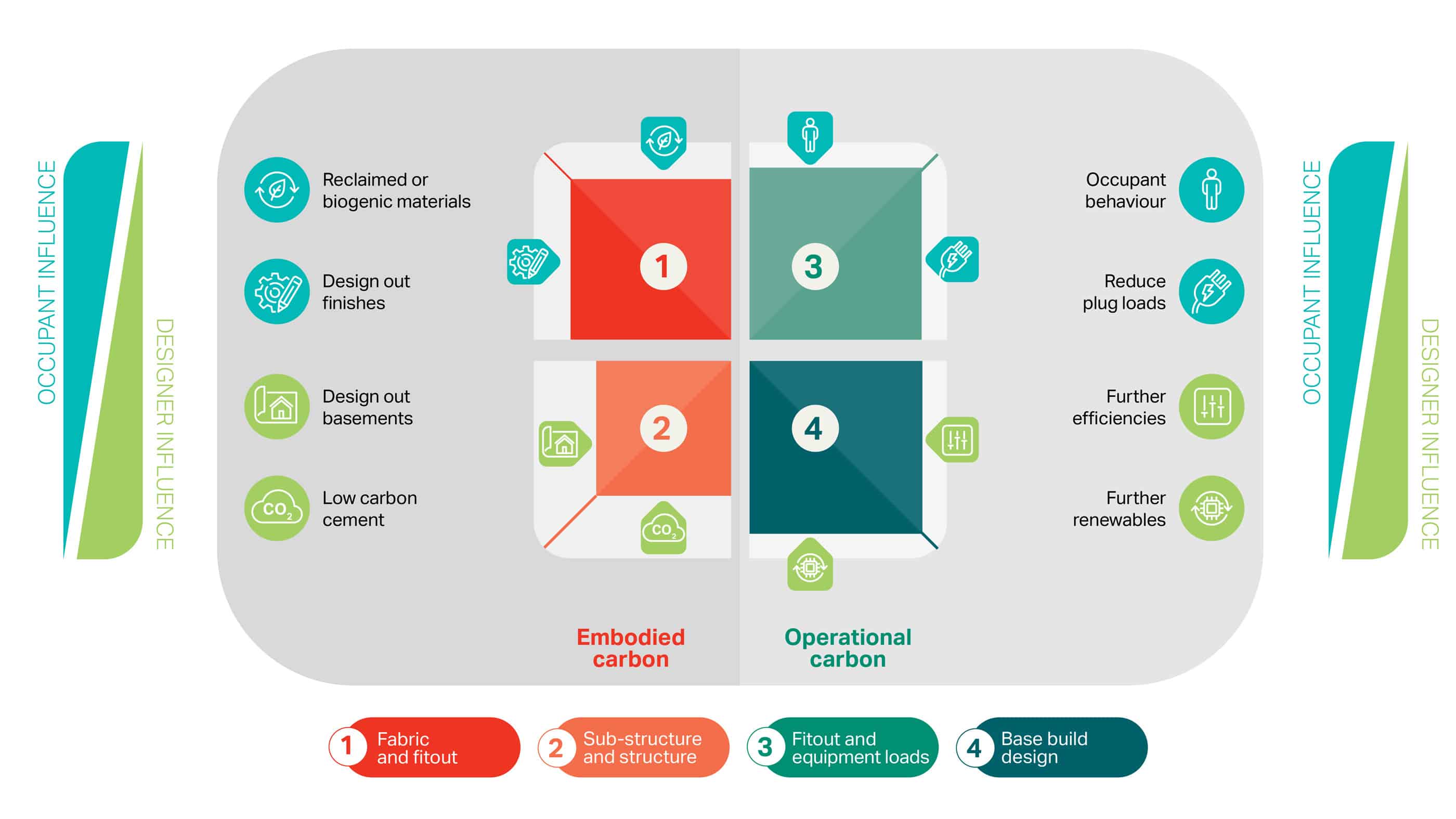

Figure 2 below shows how much potential there is to cut emissions in the substructure and structure of a typical building. Low carbon concrete will reduce emissions; cement substitutes alone can reduce the emissions by 8-20 per cent, depending on the structural solution. Designing-out basements will significantly cut embodied carbon as they require a lot of concrete to be poured. This has massive ramification on building design, particularly in cities, where basements are used to service the building.

The use of alternative materials for the structure, fabric, and fitout will cut emissions. For example, reclaimed raised floor tiles have a fifth of the emissions associated with new ones, and unfired bricks made from construction waste have a tenth of the emissions of the usual fired bricks. Lightweight façades make the whole building lighter, as well as reducing the thermal bridges created by having to tie back heavy materials.

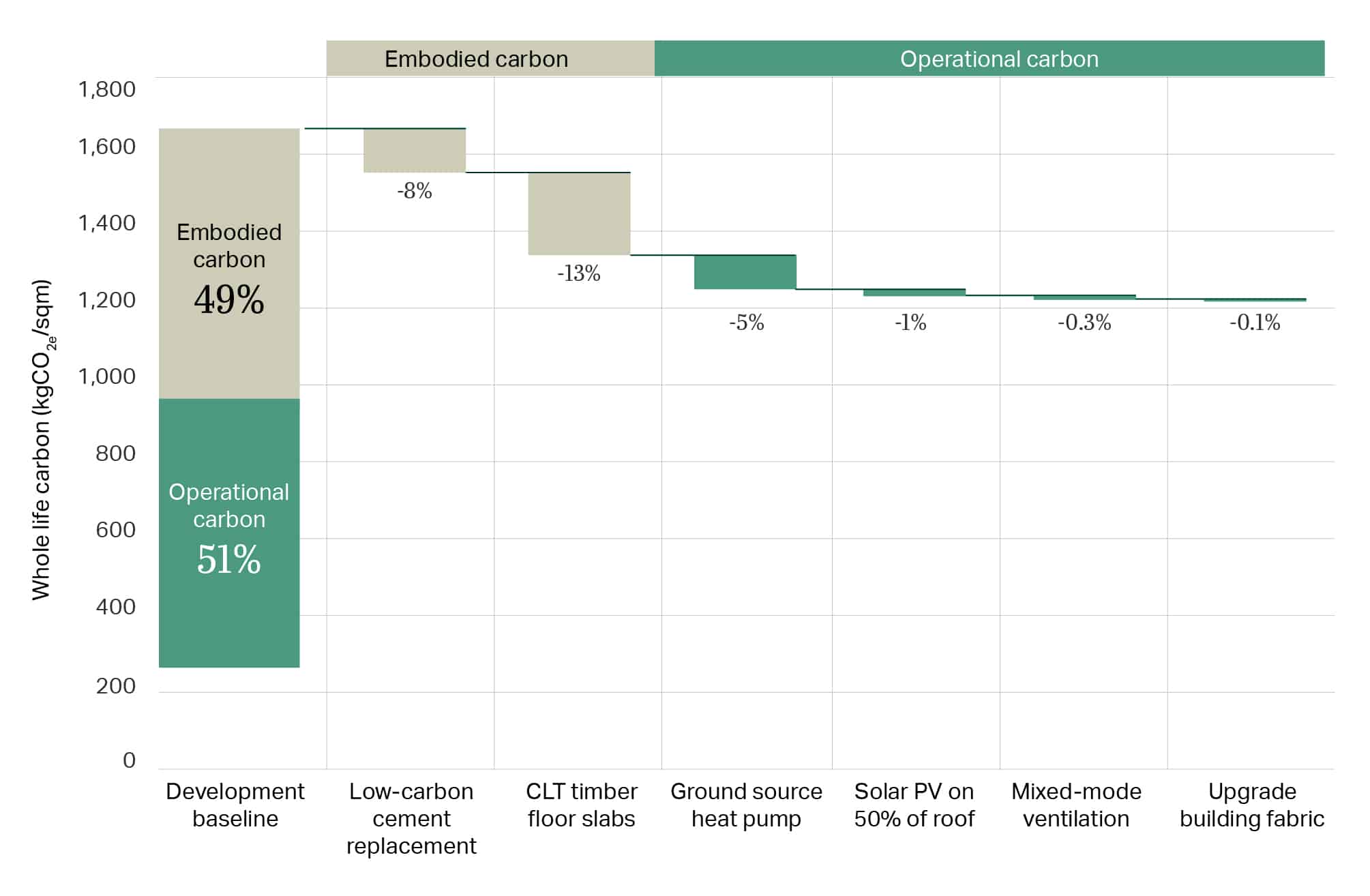

Figure 3 shows an example of a project where the key opportunities were assessed in terms of total carbon emissions. The relative carbon cost of each of these measures was also assessed and in terms of ‘cost per tonne of carbon saved’ the clear winners are the embodied carbon savings from cement substitutes. The operational savings are small as the building is already optimising the fabric, using highly efficient systems as well as ground source heat pumps and a PV array.

Using the quadrant to visualise the extent of the gap to be bridged

If we superimpose net zero emissions levels as stipulated by LETI and RIBA onto the quadrant (see dotted blue line in Figure 4), we can clearly see the extent of the gap to be bridged. To meet these targets, we need to halve emissions – and that will require radical changes to the way we design and operate buildings.

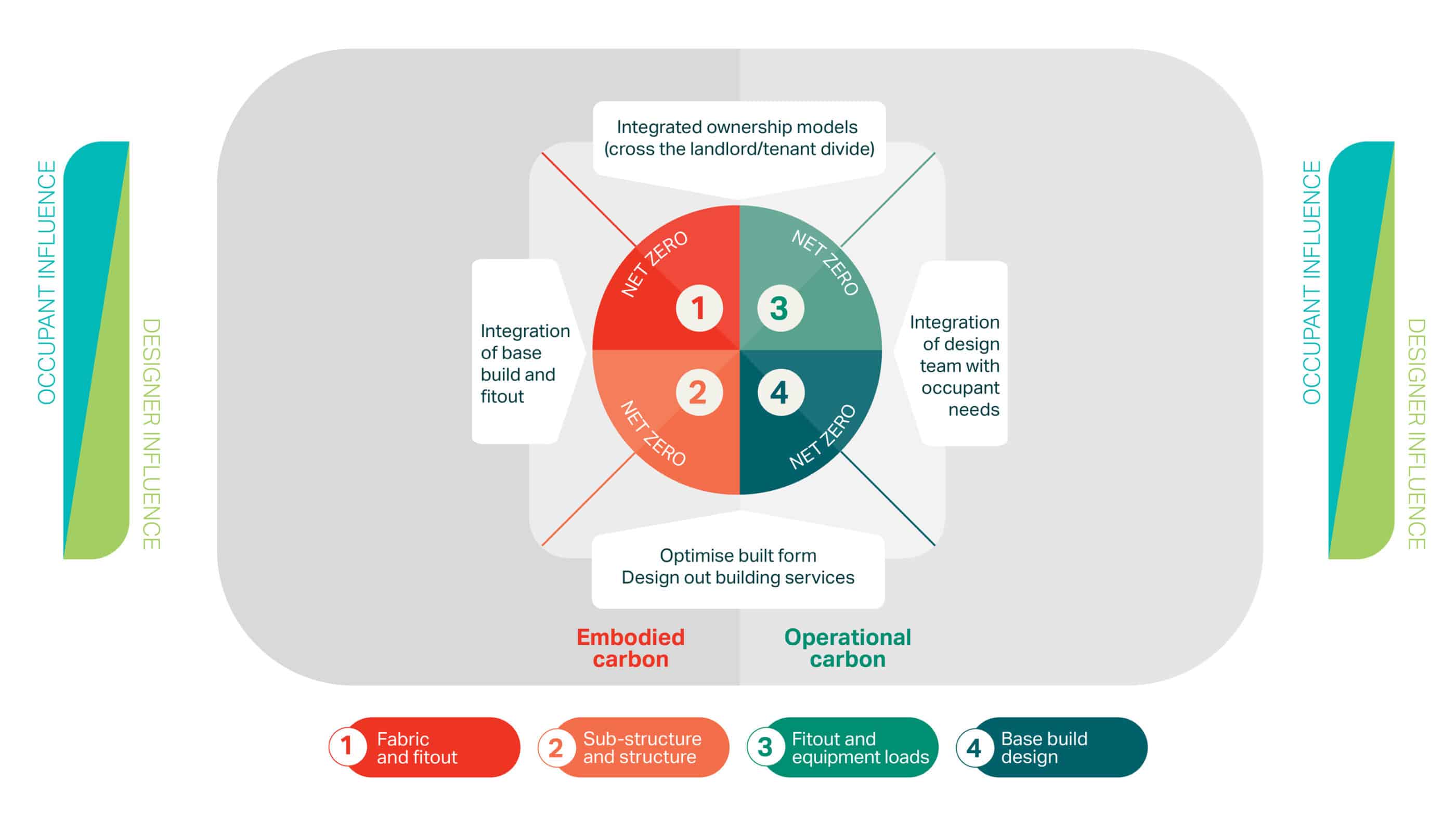

Showing the new approach

Figure 5 shows how we will have to change our whole approach to projects if we are to hit the LETI and RIBA targets.

Firstly, we need to rethink the idea of base build and fitout. Often, items are installed to let the building which are then torn out and replaced by the tenant to meet their needs. Likewise, with control systems, some large commercial buildings have two Building Management Systems (BMS) that are not fully integrated, making it difficult to understand the energy use and impossible to tightly control the systems.

To avoid the above, designers and operators will have to work hand-in-hand to optimise everything from the built form to the installed capacity of the building services to hone the building for lean design and lean operation.

Secondly, we will have to cross the landlord/tenant divide as this contractual line drawn through our buildings means that the landlord loses control over the energy demands in the building. The tenants’ demise becomes a ‘blackbox’ of energy use with occupants able to install any equipment they like and demand that the building runs 24 hours. This can lead to the tail-wagging-the-dog where one small, tenanted area can force all of the central plant to be running continuously. Then, at the end of the lease, the landlord has no records of the maintenance and warranties of the plant and equipment that is in the tenants’ demise, making it difficult to be able to keep it and pass it onto the next tenants.

The solution is to erode the line between landlord and tenant, with landlords taking responsibility for the equipment in the tenant’s demise and working closely with the tenant’s fitout team to ensure that the design fits with the net zero targets. This approach is starting to be adopted by some farsighted developers.

We need a radical rethink

Meeting the net zero challenge is going to need more than a tweaking of business-as-usual practice or a reliance on technology. We need to rethink the brief and revaluate what we expect from our buildings, in terms of everything from basements, structural solutions, building heights, through to retention and refurbishment of existing buildings instead of building new.