Embracing innovation to transform mental healthcare facilities

Awareness around the importance of good mental health is at an all-time high – but so is demand. To best deliver the next generation of mental health facilities, innovative approaches to patient care alongside a digital-led design ethos must be embraced. The evidence is already emerging.

We are witnessing a revolution in the way mental healthcare provision is delivered across the island of Ireland. New holistic care models, based around central tenets of therapy and recovery rather than isolation and institutionalisation, are informing the design and location of pioneering new facilities,

helping to destigmatise mental health.

Increasingly, innovative design methods are underpinning the delivery of these new secondary care facilities, where digital tools are leveraged to create award-winning environments that are both inclusive and nurturing, yet robust enough to ensure the safety of both patients and staff – a delicate balance to strike.

This article draws on our experience of delivering some of these new healthcare facilities – from acute services to forensic mental care and children’s support units – to demonstrate how a digital-led approach can improve delivery, increase operational effectiveness and support the person-centred care model being rolled out across the island of Ireland.

The enormous costs of poor mental health

More than one in six people in EU countries (17.3 per cent) have a mental health problem in any given year – the figures for the island of Ireland show a marginally higher percentage (18.5 per cent).

Coronavirus has added a further twist. Isolation and lack of access to formal and informal support during extended lockdown periods have been devastating for those with existing mental health issues, with some evidence from the UK pointing to an 8 per cent increase in cases as a direct result of the pandemic.

Aside from the significant human and social costs (through reduction in quality of life, depression and pain etc.), the wider economic costs are enormous – up to as much as four per cent of GDP across EU countries, or over €600 billion. In the Republic of Ireland, estimates suggest that costs amounted to 3.2 per cent of GDP in 2018.

Recommendations set out in reviews by the National Health Service (NHS)[4] and Health Service Executive (HSE)[5] have paved the way for a radical step change in the way mental health care provision is delivered to try and minimise these costs.

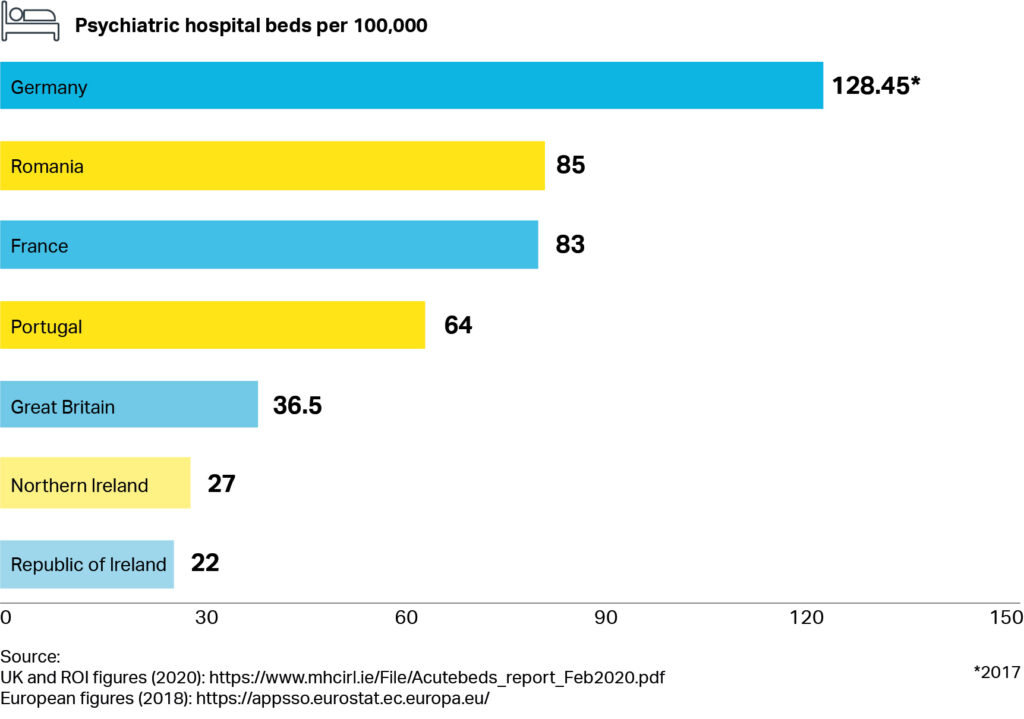

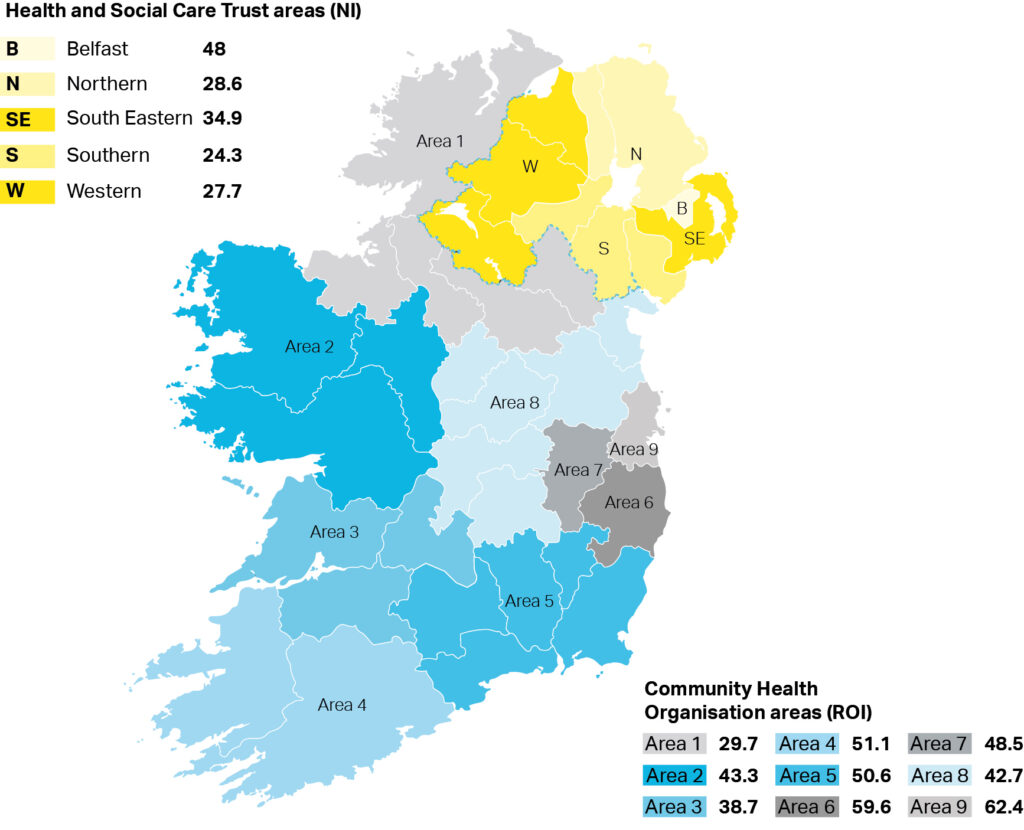

While there has been a steady if modest increase in overall gross non-capita mental health budgets in recent years, the current percentage allocation to mental health still falls short of recommended levels – and the number of beds per 100,000 across the island of Ireland is low in comparison to other EU countries (Figure 1). Demand for services is still acute, particularly in urban areas across the country (Figure 2).

New best practice is emerging

Changes in the delivery of mental health care provision have clear implications for how healthcare trusts manage, design and deliver their estates: this is where good design and technology step in.

Risk assessment is a good example. Risk assessment processes are an intrinsic part of mental health. Creating a secure environment for patients and staff is a critical requirement particularly in acute units – where patients can become distressed, disruptive and destructive with potential for self-harm, violence and even loss of life.

In the new intensive support unit for children in Glenmona in Belfast, where we needed to make the facilities as inclusive and homely as possible, we took a risk-based assessment approach to reduce the safety requirements while using cutting-edge design to ensure compliancy. In low and medium risk areas the proposed interior design means that safety and anti-ligature features can be more discretely placed, and design layouts promote line of sight limiting the amount of surface protection measures.

We took a similar approach at the Acute Mental Health Inpatient Centre – a recently-opened state-of-the-art facility located in Belfast City Hospital. There, technology has been leveraged to minimise at risk situations for both patients and staff. Isolation controls can identify water misuse allowing staff to immediately shut off supply to patient rooms. Smart electrical design removes self-harm electrocution risk.

Innovations around personal technology and sensors – applications of which continue to advance –complement the safety measures embedded within the physical building. At the Inpatient Centre in Belfast for example, radio-frequency identification (RFID) is integrated with the alarm systems enabling real-time patient and staff tracking. In case of emergency, immediate staff-assist and staff-attack response location information is communicated to site-wide display stations.

Costing benefits

Costing the benefits of these systems needs to happen early. A socioeconomic cost benefit analysis is the best way to measure the impact of an improved environment and the reduced risk to staff and patients. Generally, the more area within the building, the greater the capital cost. However, designing solely to Health Building Note (HBN) guidance can potentially impact on the therapeutic environment within mental health facilities. Careful consideration must be given to incorporating daylighting, natural ventilation and single-loaded corridors which provide good levels of natural light and views out to external spaces.

There are both positive and negative revenue and operational impacts of deviating from HBN guidance. This was demonstrated by a mental health trust who decided to increase all its bedrooms with en-suites from 15m2 (as per HBN guidance) to 23.5m2. This enabled the trust to admit patients of all levels of mobility, resulting in never having to turn away a patient who required a larger room. This decision resulted in the trust achieving the optimum 85 per cent occupancy rate which, in turn, had a positive revenue impact.

Conversely, if trusts choose to deviate from HBN guidance and drive areas too low, it can result in a smaller facility, with the same quantity of rooms, albeit smaller, and similar staffing level requirements. Smaller rooms can prevent disabled or obese patients from accessing the facility which can reduce the potential revenue that could be gained from a more flexible design approach.

The benefits of digital delivery

The best way to incorporate these enhancements is to design buildings digitally.

This is happening in Scotland where we are working with Health Facilities Scotland (HFS) and NHSScotland (NHSS) to deliver on the Scottish Government’s Digital Health and Care Strategy. The first step was to embed Building Information Modelling (BIM), which allowed NHSS to then create a digital estates strategy. One of the key components of this is the digital twin — a shift from a deterministic to a more probabilistic, dynamic model.

Via digital twinning, NHSS aims to link its physical assets (buildings and potentially end-users) to a digital representation, using data from sensors and analysing variables such as condition, efficiency and real-time status. This connectivity coupled with data analytics will reform facilities’ levels of operational effectiveness, generate extra insights from the digital twin to help reshape and improve services, and support person-centred care.

Using data to achieve parity of esteem for mental health

These facilities are at the vanguard of mental health care across the island of Ireland. Cutting edge design and technology is already improving the quality of patient care, and better protecting staff. Likewise, digital tools and processes are delivering the next generation of facilities efficiently, achieving value for money.

It is important that this momentum is not lost. Collating data and user experience evidence is the next step. In combination with in-depth cost model knowledge, a strong case can be made for further investment, and another step can be taken along the road to achieving parity of esteem for mental health.