Five key things London 2012 taught us about successful placemaking

Just ten years since the razzmatazz of the Olympic and Paralympic Games, the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park and its surrounding development have become part of London’s urban fabric. The journey of creating this new district has provided invaluable insights into large scale urban development writes Jane McEwen.

A decade after the London 2012 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games and it’s a good time for reflection on the legacy for East London and the capital as a whole.

While it would be hard to deny that the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park (QEOP) and its surrounding development has failed to clear certain hurdles that often stand in the way of success on large regeneration schemes, it is clear that the overall improvement and transformation of East London is still anchored in the original premise for the Games: the delivery of the Park; rewilding of the Lea River; extended public transport networks; new social infrastructure; new housing (although the low levels of truly affordable housing is a disappointment given the original vision) and job creation in innovative and creative industries.

AECOM led the masterplanning consortium of designers, planners, engineers and engagement specialists for the entire scheme including games-time mode and planning for legacy build-out.

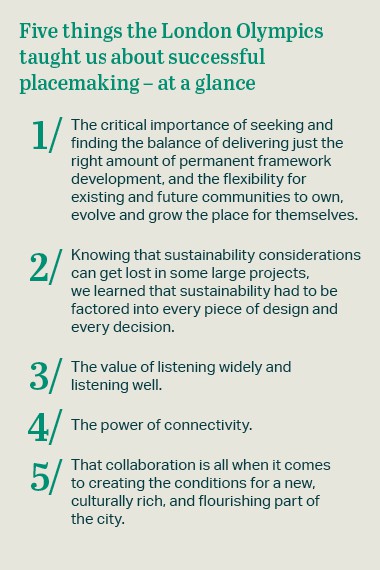

Here are five key things we learned along the way.

1/ Flexibility for the future

In masterplanning the QEOP and its legacy – as in any major project – planning for an unknown future is about creating a framework of possibilities. Flexibility has been key to the ongoing evolution from a post-industrial river valley to the setting for a global event and now the QEOP and its developments.

At this scale of development, flexibility comes in many guises. Our job was to create the opportunities for change to take place, for example designing games venues and facilities with a different future use in mind or enabling the planned Stratford Waterfront residential neighbourhood to be reimagined as the new cultural quarter.

“Our job was to create the opportunities for change to take place.”

Ultimately, we learned about the critical importance of seeking and finding the balance of delivering just the right amount of permanent framework development within a robust masterplan, flexible planning permissions and environmental assessments, which offer the opportunity for existing and future communities to own, evolve and grow the place for themselves.

2/Greenest games

The sustainability and environmental story of the games and park can be read at different scales.

At a micro level, the innovative biodiversity action plan ensured that detailed attention was paid to protecting and enhancing the habitats of the smallest animals and plants, while at the macro level, the legacy for London was a brand new, large-scale, accessible, high-quality public park.

A valuable part of the green and blue infrastructure of the city, the public park certainly demonstrated its value during the coronavirus pandemic.

Knowing that sustainability considerations can get lost in some large projects, we learned that sustainability had to be factored into every piece of design and every decision from the specification of building materials; the careful planning of bridges and roads; utilities; flood management; and the fact that all spectators (and most future residents and visitors) arrived on foot, by bicycle or by public transport.

3/Power to the people

The best lesson learned here was in listening widely and listening well. This was enabled by embedding a stakeholder engagement team with the planning and design teams, a fully integrated approach that today would be called co-creation. There was a culture of engagement and listening that became everyone’s responsibility.

In listening widely, we engaged with the broadest stakeholder groups from local residents and businesses, school children, sporting bodies and to local and city authority councillors. We heard about people’s concerns, but also their hopes, and tried to incorporate as many of their ideas as possible. The process and conversations meant we were able to develop a mutual understanding of what was possible.

Engagement is as important now as it was at the time of the Games as longstanding – and new -residents begin to own this new part of London. Efforts to embed QEOP in the local area so that benefits are more widely spread must continue.

4/Joined-up places

Connections within, across and around the park, and its integration into the fabric of the broader capital and beyond, have been critical to its success. The planning process sought to embed a network of movement, providing multiple ways for people to explore and evolve new routes, connecting people to employment and leisure opportunities. This has also stimulated organic development particularly in those areas which fringe the QEOP which have transformed into thriving new districts.

We have learned about the power of connectivity whether it’s by path or cycle way, bus routes or rail services. We are already seeing how opportunities in places like Hackney Wick or Fish Island can be opened up by a bridge in the right place, or an interesting intersection created by connections that facilitate access and movement, and that, in turn, sparks investment.

5/Stronger together

Our work was about making a place for people, so it was critical that the process had a very human dimension. This included fostering the collaboration of four host boroughs, transport agencies, local and regional government and the mayor, communities and latterly the London Legacy Development Corporation.

Collaboration also included co-locating planning and design teams from many practices, sharing offices and sharing ideas for the best solutions, enjoying the discussions and visits… all working together for the same purpose, to the same deadline for a great sense of shared endeavour.

We learned that collaboration is all when it comes to creating the conditions for a new, culturally rich and flourishing part of the city.

AECOM, leading multi-disciplinary teams drawn from the base to the London and international design and technical talent, has been at the forefront of planning and delivering the facilities and infrastructure for the London 2012 Games and the associated long-term legacy of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, as the centrepiece of the regeneration of the Lower Lea Valley in East London. Beginning in 2003 supporting the regeneration case for the bid, the AECOM consortium has encompassed multi-disciplinary masterplanning for the entire development within the Olympic Park, securing planning permissions, compulsory purchase of land by public sector agencies and planning policy development.

The masterplanning consortium comprised: AECOM (originally EDAW), Allies & Morrison and Buro Happold along with Hargreaves Associates, Foreign Office Architects, HOK Sport (latterly Populus), Symonds, KCAP, Camlin Lonsdale, Beyond Green, JMP Health Consulting, Maccreanor Lavington Architects, WWM Architects, Vogt and Arup.