Not a pipe dream? Why high-speed rail has a role in Australia

Long talked about and not yet delivered, high-speed rail is Australia’s long unrealised dream. Rail specialists Ken Bagget and Roger Jeffries explore how a regional approach could finally make high-speed rail a reality for Australia.

High-speed rail in Australia has been frequently promised through different election cycles and faced many false starts. However, the broad case for high-speed rail in Australia remains compelling if it progresses with a clear definition and purpose for investment.

Since the deregulation of commercial aviation in Australia in 1990, the east coast golden triangle of Melbourne-Sydney-Brisbane has been the holy grail of long-distance travel, driving airline travel demand and profitability. The Melbourne to Sydney corridor, one of the world’s top 5[1] busiest air travel corridors, has logically been the focus of several previous efforts to establish high-speed rail in Australia. Still, despite a strong domestic travel market on this corridor, key challenges remain: the cost of land, complex land ownership and stakeholders, challenging topography, existing road and rail infrastructure, natural environmental features like mountains, rivers, wetlands, and protected environments, mean a high-speed rail corridor has proven too great a challenge.

So, is there any case for high-speed rail? And can it play an effective role in Australia’s transport network?

The benefits

1/ Economic and social vitality

High-speed rail creates broad economic benefits for regional centres. High-speed rail construction, operation and maintenance require significant investment, creating skilled job opportunities in engineering, construction, and manufacturing. Unlike airports and major motorways, which often become a blot on a landscape, high-speed rail corridors require less land acquisition and can enhance urban environments. The permanent infrastructure assures private and public investors, can spur development in regional areas, and the increased connectivity provides better access to employment, education, healthcare, and recreational facilities. With greater access to amenities, we could reduce the concentration of population and economic activity in major cities, leading to more balanced regional development and addressing urban sprawl.

2/ Adjusting to our changing work habits

The significant shift to hybrid work-from-home models, amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, means more people are moving to regional areas. High-speed rail offers comfortable, affordable, and productive regional commuter travel, and the ability to viably work while travelling on a high-speed rail service means transit time can be used as valuable work time. Unlike air travel, with the right technology solutions, commuters can experience minimal downtime while travelling, making longer-distance commuting more attractive and improving work-life balance.

3/ Sustainability and resilience

Globally, the transport sector is responsible for approximately one-quarter of greenhouse gas emissions[2]. High-speed rail can be powered by renewable energy and offers an efficient alternative to carbon-intensive transportation options for travellers. It provides a more sustainable travel option that can alleviate increasing congestion on highways and airports and help reduce reliance on fossil fuel-powered vehicles. Rail offers significant value for energy expended. The International Energy Agency reports that rail carries 8% of the world’s passengers and 7% of freight, yet accounts for just 2% of transport energy use[3].

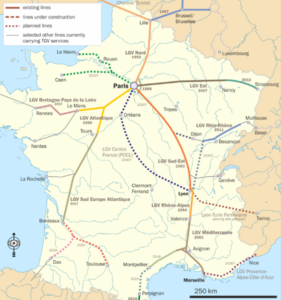

Effective mass transit, high-speed rail networks also support decarbonisation efforts and, in some cases, form the basis of ambitious climate policy. To cut carbon emissions, the French parliament is leveraging the established high-speed rail network, passing a bill to ban short-haul flights where a train alternative of 2.5 hours or less exists.

Shifting perception – where does high-speed rail have a role?

International high-speed rail network development case studies demonstrate how a broader program of high-speed rail networks could be developed in Australia in jurisdictions with similar planning, environmental, and socio-political systems.

Many systems have been developed using building blocks and staged implementation, leveraging existing connections between towns and cities, both intra- and inter-regionally, including existing rail networks. They build upon existing land use, travel demand patterns, and infrastructure to create high-speed rail networks for the future.

Recent global high-speed rail developments such as Brightline Florida, Stage 1 (115 kilometres) and California High-Speed Rail, Stage 1, Section 1: Bakersfield to Fresno (175 kilometres) have followed this exact path. Doing so creates an implementable, cost-effective staged plan for delivery, with significant potential for further development of the rail system and land use at key nodes. These projects follow a similar pathway to many European high-speed rail systems in operation or development, such as:

- Paris to Lille in France (LGV Nord, one of the earliest European examples, opening in 1993, at 220 kilometres)

- Seville to Cordoba in Spain (140 kilometres, one section of the longer Madrid – Cadiz high-speed rail corridor)

- High Speed 1 in the UK (110 kilometres, the UK section of the longer London to Paris high-speed rail)

- High Speed 2 in the UK (180 kilometres).

In the Australian context, these case studies present parallels to corridors in consideration such as Sydney to Central Coast (60 kilometres) and Newcastle (120 kilometres total), Sunshine Coast to Logan (120 kilometres) or Melbourne to Geelong (80 kilometres). We must shift our perception of what high-speed rail should be and consider where it is both achievable and logical. In Australia, this means reconsidering high-speed rail in a regional context rather than long-distance inter-city rail between state capital cities. Instead, inter-regional rail would connect our growing regional centres to cities.

With more achievable distances compared to inter-city rail, inter-regional rail could be delivered using a program of works approach and, where possible and practical, utilising and upgrading existing rail corridors and infrastructure to significantly higher speeds to form part of a high-speed rail network.

Ultimately, inter-regional rail does not need to preclude any major intercity connections but can catalyse these longer connections when we are ready. Globally, many successful high-speed rail projects are designed to connect urban centres that are modest distances apart, around 150 kilometres. Continually, cost is the key barrier to delivering high-speed rail and focusing on shorter distances makes these projects attainable.

1 According to: https://www.oag.com/busiest-routes-right-now

2 According to: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/energy/what-we-do/transport

3 According to: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-rail