Unlocking the benefits of infrastructure investment

Infrastructure has a role to play in helping the economy recover from coronavirus. Given the scale of disruption, we have an obligation to see taxpayer funds used as effectively as possible. To do this, AECOM’s Ken Bagget says we need to seize the opportunity to fix issues that have long been ignored.

In times of crisis, government often turns to infrastructure to stimulate economic recovery. Throughout 2020 – a year of constant crisis – infrastructure investment was again recognised as a way of maintaining economic activity and protecting jobs. This led to governments across Australia and New Zealand, increasing spend on existing projects and finding additional funds to bring new projects to market sooner.

Importantly, throughout the pandemic, project staff were classified as essential workers enabling the design and construction of major transit projects to continue at pace. Together, these factors managed to shore up sector confidence, protect jobs and soften the financial impact of lockdowns.

But success throughout 2020 served to highlight and, in many cases, exacerbate, pre-pandemic challenges relating to shortages of talent and materials, risk imbalances and pipeline uncertainty. All these factors contribute to cost overruns, project delays and capacity concerns.

While small cost overruns on small projects can be challenging, today we are in the era of the ‘mega’ transport project (those costing AU$1billion/US$775m or more). Where overruns account for hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars.

According to the Grattan Institute report, ‘The rise of megaprojects: counting the costs’, ‘Australian governments are committing to a record number of ‘mega’ transport projects, and that exposes taxpayers to mega risks of cost blowouts. Ten years ago there was just one transport infrastructure project in Australia worth more than $5 billion. Today there are nine, and costs have already blown out by AU$24 billion on just six of them.’

Over the past two decades, Australian governments spent AU$34 billion more on transport infrastructure than they originally planned to, that equates to three times the AU$11.5 billion annual Federal Government infrastructure spend committed to in the 2020-21 budget.

As vaccines continue to roll out and economic disruption dissipates, the onus is on our industry to ensure that the investment unlocks as much potential as possible. To do this we need to fix long term structural issues impacting confidence, productivity and efficiency. Or face the prospect of infrastructure investment and delivery continuing to underperform and constrain long-term economic growth.

In the following section we address two long-running issues, exacerbated by the crisis, which threaten to curb the benefits infrastructure can bring.

Talent constraints

The road and rail industry face significant talent shortages which are expected to drive up wages in the next 12 to 18 months. Some of the most challenging roles to fill are essential to project delivery, and the inability to source talent from overseas may cause delays. Typically, global engineering professionals are very mobile, but caps on international arrivals and restricted quarantine capacity make it extremely difficult to access this talent pool.

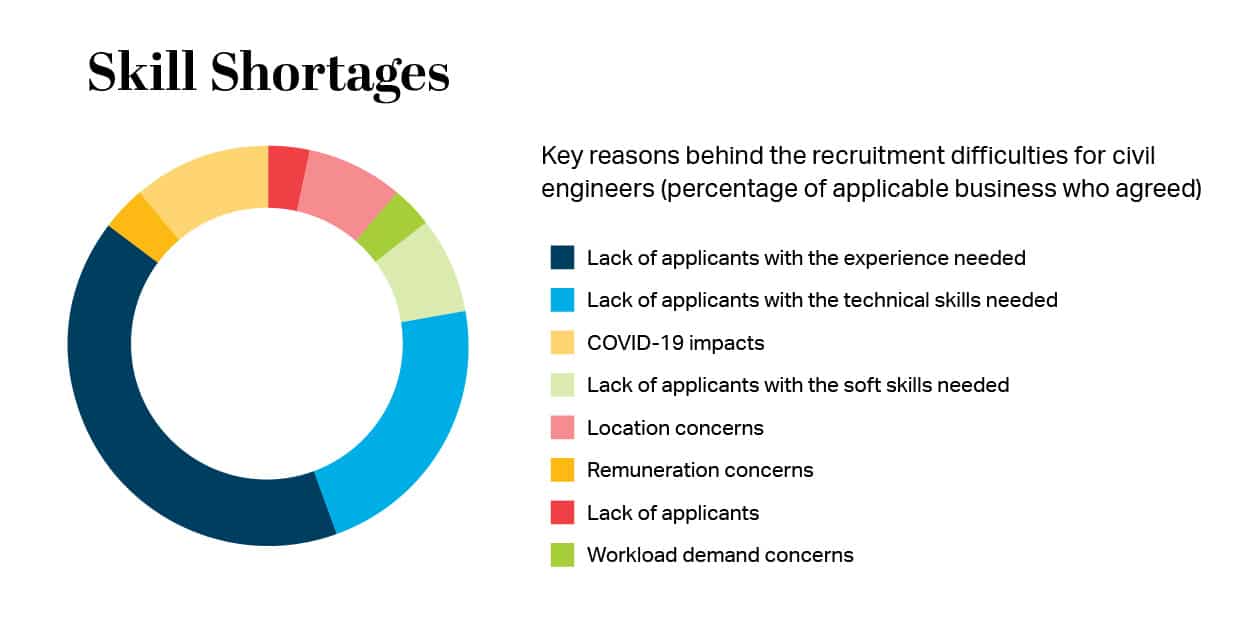

The main challenge is the lack of experienced and qualified individuals available in the local talent market, according to a December 2020 survey by Consult Australia, the industry body that represents the design, advisory and engineering businesses in Australia.

For large transit projects, it is standard practice to recruit international technical experts to support, train and develop the specialist local capability. Given the number of complex metro projects in the works across Australia and New Zealand, there are shortages of skilled people with experience in rail systems, underground station design, tunnelling, construction and project integration.

In the years prior to the pandemic, AECOM Australia and New Zealand recruited up to 15 per cent of critical technical talent on large projects from overseas. This has dropped to 1 per cent in the past 12 months. The ongoing ban on international travel contributes to a lack of talent that threatens the delivery timetable for the current pipeline of major projects.

The domestic engineering and construction workforce – and particularly those skills across road and rail – will also see their value soar as the market fights for talent, significant wage inflation will be the result.

When global talent is not available or specific technical skills may not be on hand locally, AECOM uses its network of international design centres to augment the local talent.

Unfortunately, various state and territory government restrictions on the percentage of work permitted to be completed outside of Australia (often limited to 5-10 per cent) mean there is a limit to this model’s effectiveness in addressing current onshore skills shortages.

We would welcome the easing of these restrictions in response to the current lack of international flights or economic migrants. This is the ideal time to differentiate between local content ratios for professional consulting services (i.e. design engineers) and site-based contractors or trades.

Unsustainable delivery risk

Many of the largest contractors based in Australia and New Zealand are at, or nearing, capacity. They are facing the same talent shortages and are increasingly likely to decline to bid major new projects as a result of the increasing risk burden under certain procurement models.

These issues contribute to a lack of competitive tension in the marketplace, project costs are driven up, commercial models require adjusting, and project delays are the result.

As confidence and economic activity return to pre-pandemic levels, national government in New Zealand and state and territory governments in Australia may find that the markets view on the need to share delivery risk is hardening.

Encouragingly, there has been a return to more collaborative, alliance-style contracting models in many jurisdictions, perhaps a recognition of their effectiveness in procuring most of the mega metro and transit projects. That said, the transit industry thrives on certainty, and there is at present a lack of it across three main areas:

- Certainty of delivery model: considering the length of time mega projects take to be scoped and procured providing certainty to the industry about the commercial model is likely to create more competitive interest from the market and a better outcome for the taxpayer

- Certainty of timing: enhanced pipeline visibility allows better resource planning

- Certainty of design: a detailed and rigorous reference design can help respondents better understand and manage risks that they are expected to own

With more certainty – projects can be delivered with more confidence.

Collaboration is the key

Governments across Australia and New Zealand are committed to delivering an infrastructure pipeline to meet the post-pandemic challenges. And in turn support jobs that sustain economic recovery.

But without the skilled workforce to deliver these infrastructure projects, and without the certainty of robust delivery models, or pipeline visibility the positive impacts of additional infrastructure investment may not be realised. After such a difficult 12 months, I’m sure no one wants to waste this year’s big opportunity.