Resilience and a capitals approach

Resilience is a challenge and a priority for water companies. Here we explains how, by looking beyond financial and built capitals, water companies can deliver reliable services to customers and manage the resilience they need to thrive as businesses.

Today, resilience is a huge priority for water companies, who face more challenges than ever — from increasing customer demand for better services, to demonstrating stability to investors.

But resilience in the water sector is about more than coping with and bouncing back from service disruptions. According to Ofwat, the economic regulator of the water sector in England and Wales, UK, resilience is also about anticipating trends and variability to maintain services for people and protect the natural environment now and in the future.

Ofwat has made resilience one of its four key themes in its 2019 Price Review, putting water companies’ approaches to managing resilience under the spotlight. The regulator has also made it clear that water companies will no longer generate returns to their investors through financial levers such as beating the cost of capital for example, but by delivering a great service to customers and wider society. By tapping into other capitals, such as natural, social and human capital, as well as financial and built, water companies can stay financeable and more resilient in the long run.

The capitals

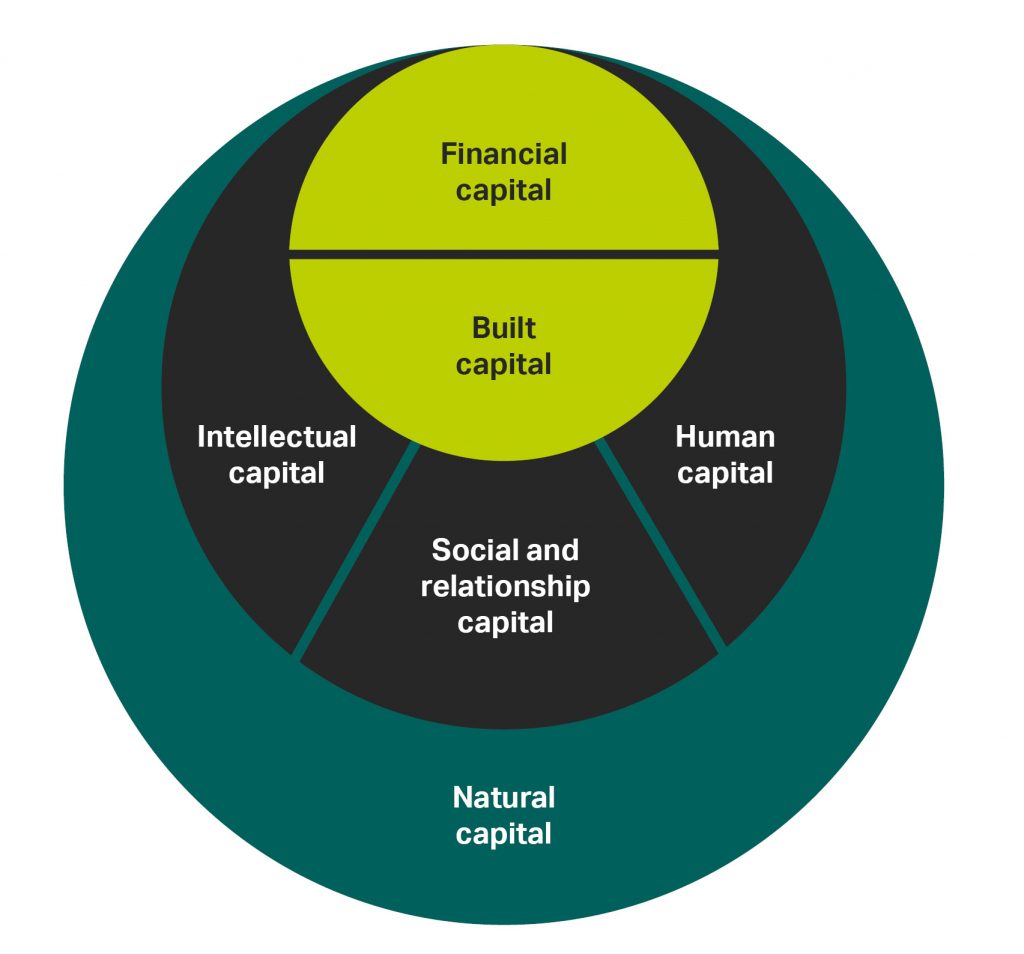

Organisations depend and impact on many types of capital, including financial, built, natural, social, intellectual and human capital.

The capitals approach

We look at two key risks for water companies— too much water, and too little water — to show how water companies can integrate a capitals approach to grow resilience.

The capitals in action

Each type of capital includes assets that provide a flow of benefits to organisations: by investing in different types of capital, water companies can make better-informed business decisions and deliver more reliable services to customers.

Too much

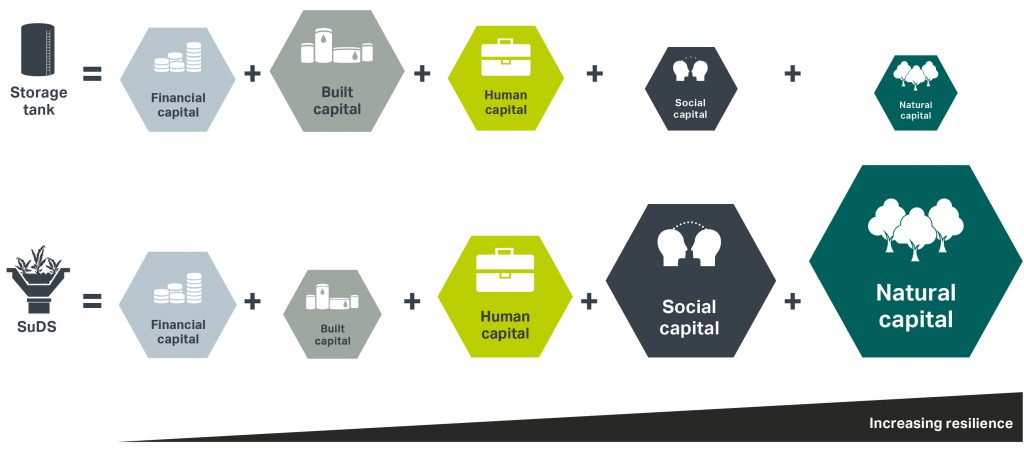

To be resilient in times of flooding, a water company might traditionally build a large storage tank or divert excess flows to watercourses to prevent flooding. But by also investing in sustainable drainage measures within urban centres, such as planting grassy verges or creating wetlands, it’s possible to store, soak up and slow down the flow of rainfall naturally, reducing pressure on existing drainage systems and the environment.

Making use of natural capital in this way has wider benefits over and above preventing sewer flooding — it can lead to further natural capital benefits such as the creation of habitats for wildlife, as well as social and human capital benefits such as improved local air and water quality and enhanced local wellbeing and amenity through the creation of green spaces.

Generating extra value and resilience through a capitals approach

By using different types of capital to inform investment decisions, water companies can generate extra value and increase resilience for the same financial capital cost.

Too little

Traditionally, a water company might impose water use restrictions during times of drought and high water demand to reduce the chance of more severe service interruptions. But by allocating land in an upper catchment to act as a natural reservoir, it is possible to soak up and store rainwater naturally so it can be released more slowly downstream, smoothing out peaks and troughs in water supply. From a drought management perspective, this creates a store of water that’s more gradually available over time, and also reduces water discolouration. This approach leads to wider natural, social and human capital benefits such as increased biodiversity and the creation of space for recreation and learning.

United Utilities and South West Water, among others, have upland management schemes in place to address quantity of flow in this way, which not only ensures more water is available when it is needed most, but slows run off, improving the quality of the water they provide to customers, meaning they don’t have to treat it as much – saving them money while reducing their carbon footprint. Water companies can also use education campaigns — a good example of social capital— to encourage customers to use water more responsibly. This reduces demand and wastewater flow into sewers, which can lower pumping costs and associated carbon impacts.

Putting theory into practice

Water companies can evaluate and estimate the financial value of the benefits generated by investing in the capitals using physical metrics and financial valuation methods, as we are doing with Yorkshire Water. By including these values in their business and investment plans, Yorkshire Water is able to compare and contrast the cost and wider benefits of different solutions to managing water in line with their business priorities – this means they are able to make better-informed decisions not just based on financial capital, but also the natural, social and human capital benefits generated.

By including all capital values in business decision making and investment plans in a more holistic way, water companies are more likely to assure investors and regulators that their performance, be that in terms of service or financial measures, is resilient and sustainable, and should encourage greater investment.

AECOM innovation: resilience scorecard

Since 1950, New Orleans has endured 11 named hurricanes and countless extreme weather events. The most devastating was Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when levees failed and the city was flooded. More than 1,800 people lost their lives and thousands of businesses and residents were impacted with capital losses estimated between US$108 billion and US$135 billion.

AECOM and IBM worked together to develop the United Nations Disaster Resilience Scorecard for its Making Cities Resilient Campaign. We used the scorecard, which provides a set of assessments that help cities understand how resilient they are to natural disasters, to develop a detailed survey to assess the disaster preparedness and resilience of 208 businesses located on six historic commercial corridors within New Orleans.

The survey results led to us making recommendations for the City of New Orleans and business owners to improve the resilience of the business corridors to flood risk, including maintaining corridor drains so that they are not clogged; considering green infrastructure such as rain gardens in abandoned lots or existing green spaces; and establishing and strengthening neighbourhood groups that regularly discuss disaster preparedness – examples of natural, social and human capital in action.