Rethinking planning: 10 big changes the forthcoming English reforms should address

The Prime Minister has promised the biggest reforms to the planning system in England since World War II, with rumours of a whole new approach to zoning and simpler statutory plans to accelerate housing delivery. A Planning Policy paper setting out the reforms and proposed new legislation is expected very soon, with a fast track through Parliament in autumn 2020.

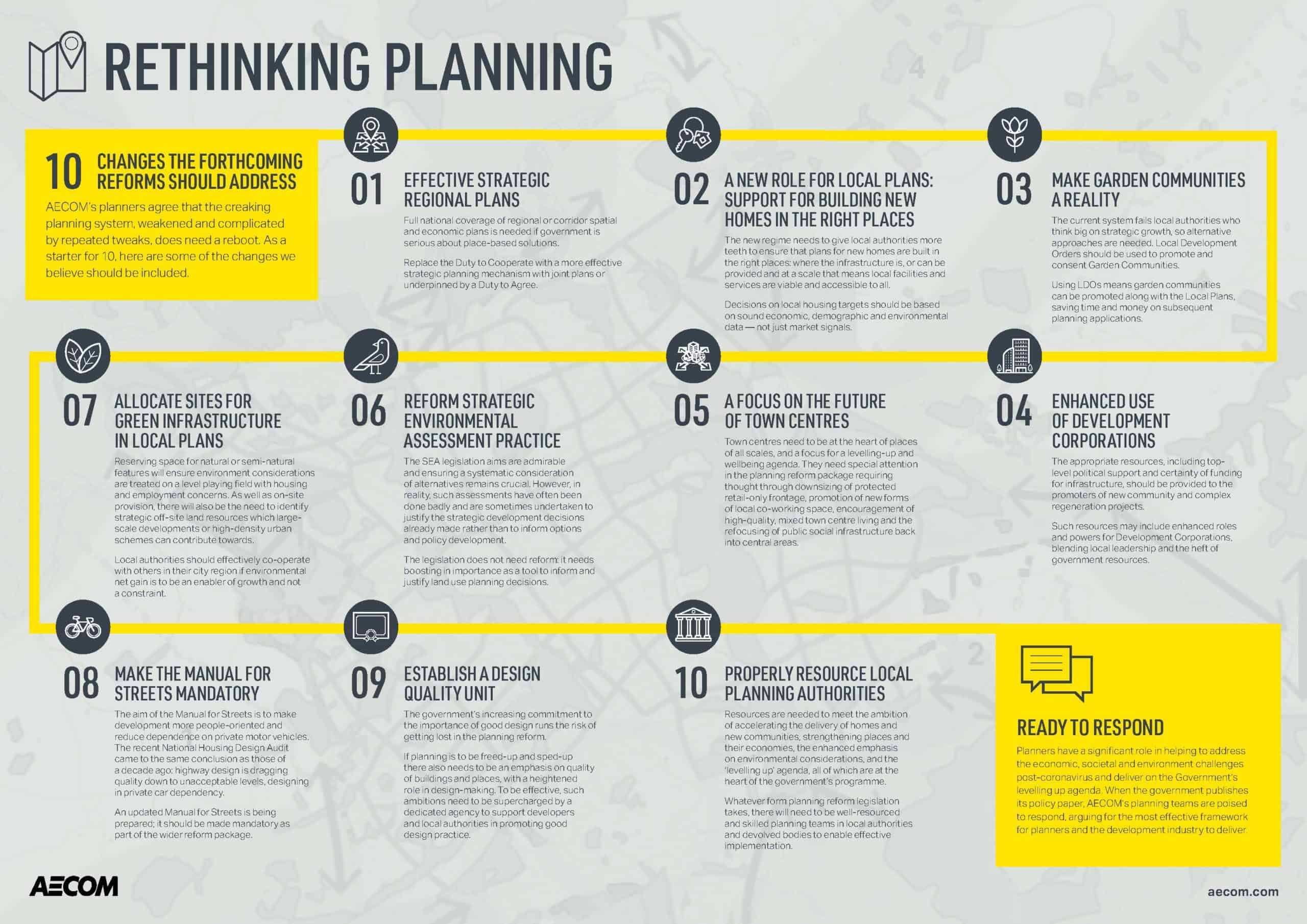

AECOM’s planners agree that the creaking planning system, weakened and complicated by repeated tweaks, does need a reboot. But we argue that the English system needs to be joined-up and visionary rather than continuing to rely on a piecemeal approach.

Much of the media commentary has been about changes to development management to underpin recovery and as stimulus to the development industry. The main thrust of which is to make it easier – or no longer necessary – to secure planning permission. On its own, such deregulation will not create the future places and communities we need, nor will it enable well-rounded decisions to be made on where to build, regenerate or protect.

As a starter for 10, here are some of the changes we believe should be included in the forthcoming reforms:

1.Effective strategic regional plans

Unlike the devolved nations of the UK, England (with the exception of London) does not have full statutory planning above the local level. Indeed, England is the only country in Europe lacking a regional or national vision. This means big decisions on growth must be made at the sub-regional scale – a big ask for local authorities with different ways of doing things, limited capacity and competing priorities.

Development corridors such as the Oxford-Milton Keynes-Cambridge arc, focussed around common economic, infrastructure or community priorities are already going some way to address this gap by bringing together stakeholders to achieve shared outcomes. Similar approaches are needed across areas where transformative infrastructure is to be targeted – the Northern Powerhouse Rail/Trans-Pennine corridor, perhaps?

If government is serious about place-based solutions to balance development pressures in over-heated areas and levelling-up the under-performing parts of the country, it must ensure that regional or corridor spatial and economic plans are considered at the national level. A new devolution white paper is promised for the autumn and regional planning must form part of the toolkit.

Under the current system, there are significant barriers to sub-regional and corridor-scale growth. If this can’t be done at an England-wide level, we recommend replacing the shambolic Duty to Cooperate – introduced in 2011 to require local authorities to work together on strategic planning issues – with a more effective strategic planning mechanism. A requirement to produce joint plans is needed, underpinned by a “Duty to Agree”. A developed regional spatial planning structure will provide the context for this shift of emphasis.

2. A new role for Local Plans: Support for building new homes in the right places

With regional spatial plans in place, Local Plans will be able to focus better on local issues. The new regime needs to give local authorities more teeth to ensure that plans for new homes are built in the right places – i.e. where the infrastructure is or can be provided and at a scale that means local facilities and services are viable and accessible to all. This could mean that housing demand is met by development in adjacent authority areas if this is the more sustainable location, aligning to transport infrastructure and avoiding environmental or flood risk areas.

This approach would support genuinely sustainable development rather than the current developer-led process which can result in piecemeal growth in areas which aren’t necessarily well served by public transport. In such areas, developers or government investment should provide the infrastructure upfront – which includes education, medical and social provision to build cohesive communities.

To meet the government’s target of building 300,000 new homes a year and to deliver on the levelling up agenda, a national system is required to ensure development happens around the country in places which make sense. Decisions should be based on sound economic, demographic and environmental data – a departure from planning based on market signals, which has focussed development in the places where land values are highest rather than lower demand places where investment is needed. This will need to be underpinned by public sector infrastructure investment and direct delivery to de-risk and incentivise the market.

3. Make garden communities a reality

Garden communities are large-scale strategic new developments of at least 1,500 dwellings – usually urban extensions or stand-alone new communities. These new community developments need bespoke planning approaches which can accelerate growth but maintain quality and flexibility over 10-20 years of delivery. The current system fails local authorities who think big on strategic growth, so alternative approaches are needed. Local Development Orders, already on the statute books, which provide permitted development rights for specific types of development in defined locations, should be used to promote and consent Garden Communities rather than Development Consent Orders, which are required for large developments deemed nationally significant infrastructure projects but are not flexible to the changing needs of a community development as it grows and matures.

Using LDOs means garden communities can be promoted along with the Local Plans, resulting in a more evidence-based examination. If granted alongside the Local Plan, there will be no need for a subsequent outline planning application, saving time and money.

4. Enhanced use of Development Corporations

Promoting the larger Garden Community programmes (potentially for 20,000 or more homes) is beyond the capacity of many local authority planning departments and, indeed, the planning system itself. Similarly, major regeneration projects which bring urban land back to economic or environmental purpose require the mediation of so many stakeholders that their development is often fraught with delay. In addition, if local authorities are resource constrained then there are only a handful of master developers and developer/investors able to work at the scale of the complex and transformative brownfield and greenfield projects we expect in the coming years.

The appropriate resources, including top-level political support and certainty of funding for infrastructure, should be provided to the promoters of new community and complex regeneration projects. Such resources may include enhanced roles and powers for Development Corporations, dedicated bodies set up to deliver large-scale and complex development, blending local leadership and the heft of government. Such delivery bodies have an excellent track record in delivering sustainable growth at this scale – particularly from the 20th century new town programme. Government is considering1 a potential wider role for them to facilitate growth. The corporation model may also create the context and certainty of commitment that developers and investors need to engage in some of the most complex urban projects. Accelerating the use and powers of development corporations should form part of the planning system review.

5. A focus on the future of town centres

Much of the drive from government for planning reform has centred on the need to accelerate housing delivery. Recently, the decline of retail has pushed the challenge of supporting struggling town centres to the fore and significant resources are now being channelled into the Towns Fund schemes. However, the economic impacts of coronavirus have highlighted the structural fragility of town centres. At the same time, new value has been placed on local services and retailers who’ve been serving local communities during lockdown.

To flourish, town centres need to be at the heart of places of all scales, and a focus for a levelling-up and wellbeing agenda. This will not be achieved by flexible permitted development or changing the Use Classes Order to make it easier to change the function of a building or land. Town centres need special attention in the planning reform package requiring the thought through downsizing of protected retail-only frontage, promotion of new forms of local co-working space, encouragement of high-quality, mixed town centre living, and encouraging the move of public social infrastructure back into central areas.

6. Reform Strategic Environmental Assessment practice

Planning reform needs to add a new land use dimension – the enhancement of environmental and wildlife assets. The new Environment Act2 formalises the concepts of Environmental and Biodiversity Net Gain from building and infrastructure developments. Consequently, it is essential that this requirement is reflected in new planning legislation.

The Strategic Environmental Assessment Regulations3 already require the potential environmental effects of development to be considered alongside social and economic issues4, embedding environmental assets in land use plans. However, to value environmental capital equally alongside economic and housing priorities, the SEA needs to be at the heart of policy creation. In particular, it should inform how the unbuilt environment can make a positive contribution to growth opportunities and to tackle climate change impacts. This work should include the comprehensive review of Green Belts so that they are no longer a passive constraint, but can contribute fully to housing needs, where appropriate, and to environmental and biodiversity capacity close to our metropolitan areas.

The SEA legislation aims are admirable and ensuring a systematic consideration of alternatives remains crucial. However, in reality such assessments have often been done badly and are sometimes undertaken to justify the strategic development decisions already made rather than to inform options and policy development. The legislation does not need reform. It needs boosting in importance as a tool to inform and justify, not just post-rationalise, land use planning decisions.

7. Ensure sites allocated for green infrastructure in Local Plans

Reserving space for natural or semi-natural features will ensure environment considerations are treated on a level playing field with housing and employment concerns. For many developments, this will involve a requirement for on-site provision. When large-scale developments or high-density urban schemes cannot provide suitable provision locally, they will also need to identify strategic off-site land resources. Funds from developers should be channelled into the restoration and long-term protection and management of these natural sites.

To realise the greatest benefits of the pooling land and financial resources, landowners and local authorities need to work together to identify and protect the identified areas. If environmental net gain is to be an enabler of growth and not a constraint, this is another area where local authorities may need to effectively co-operate with others in their city region. Planning reform should look to embed the identification of net gain locations, informed by the SEA process, in strategic and local plans.

8. Make the Manual for Streets mandatory

The anticipated planning reform legislation will focus on planning delivery in England, but the primary legislation should not overlook issues of quality. To bring to life the government’s ‘Building Better, Building Beautiful’5 agenda and to improve the attractiveness of active travel (walking and cycling), the reform package should address the long overdue need to improve the quality of streets and urban realm. The recent National Housing Design Audit came to the same conclusion as those of a decade ago: highway design is dragging quality down to unacceptable levels, designing in private car dependency.

Originally published in 2007, the Manual for Streets provides guidance for practitioners in England and Wales involved in the design and planning of new streets. The laudable aim of this national guidance is to make development more people-oriented and reduce dependence on private motor vehicles. An updated Manual for Streets is being prepared: it should be made mandatory as part of the wider reform package.

9. Establish a Design Quality Unit

We welcome the government’s increasing commitment to the importance of good design6 but this runs the risk of getting lost in the planning reform proposals. If the planning system is to be freed-up and sped-up there should at the same time be an emphasis on the quality of buildings and places. Indeed, quality should have a heightened role in informing design-making. To be effective, such ambitions need to be supercharged by a dedicated agency to support developers and local authorities in promoting good design practice.

10. Properly resource local planning authorities

Our final point concerns local authorities’ ability to respond. Whatever form planning reform legislation takes there will need to be well-resourced and skilled planning teams in local authorities and devolved bodies to enable effective implementation.

Cuts to local authority budgets over the past decade7 have resulted in very limited capacity to develop and implement policies and projects needed to advance levelling up. Developers have long called for the proper resourcing of planning authorities to enable efficient and high-quality processing of proposals. Even before the full impact of the coronavirus pandemic was felt, some were saying that it was “ambitious”8 for local authorities to meet the 2023 target for getting a Local Plan adopted, with two-thirds of councils lacking an up-to-date plan9.

Today, lost income related to the coronavirus lockdown has hurt the finances of many local authorities10, with planning departments particularly affected. Implementing and delivering a new planning system requires adequate resourcing, which should be part of the reform package.

Ready to respond

Planners have a significant role in helping to address the economic, societal and environment challenges post-coronavirus and deliver on the government’s levelling up agenda. When the government publishes its policy paper, AECOM’s planning teams are poised to respond, arguing for the most effective framework for planners and the development industry to deliver.

[3] Environmental Assessment of Plans and Programmes Regulations 2004

[4] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/strategic-environmental-assessment-and-sustainability-appraisal

[6] https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/building-better-building-beautiful-commission#reports

[7] https://www.centreforcities.org/reader/cities-outlook-2019/a-decade-of-austerity/

[8] https://www.planningresource.co.uk/article/1678416/why-councils-may-struggle-meet-governments-new-local-plan-deadline

[9] https://www.theplanner.co.uk/news/two-thirds-of-councils-have-no-up-to-date-plan-suggests-research

[10] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/jul/13/english-councils-poised-cuts-services-job-losses-loss-commercial-income