Smarter, greener, better for you

This article explains how to design workplaces that use less energy, create fresh air from within and are good for those who work inside of them.

When designing a high-performance building, we ask ourselves: how much can we reduce overall energy consumption? How much can we improve the indoor air quality? How much more daylight can we get into people’s living and work spaces on a daily basis? It’s about connecting everything together to increase overall performance of the building — and of the people inside.

What makes a building high performance?

While it’s important that organisations become more environmentally friendly, the major cost inside workplace buildings is people. So, it makes sense to help people who work inside of them to be healthy and feel well.

When we talk about a building’s energy footprint, we mean anything that we do to create comfort for occupants, from balanced lighting to thermal management. In a high-performance building we look to reduce artificial lighting, for example, by using window arrangements at the building façade that let enough natural light in, while keeping the heat out: daylight is vital in aligning our natural body clocks, making us healthier people and more likely to make better decisions, increasing productivity.

In fact, results from Harvard University’s 2015 The Impact of Green Buildings on cognitive function study, where 24 people were exposed to both green and typical building conditions over six days in an environmentally-controlled office space, show cognitive scores were, on average, 61 per cent higher in the green building conditions, with CO₂, VOCs and ventilation all having significant, independent impacts on cognitive function.

While individual parts of high-performance buildings increase initial capital costs, the greater the number of parts, the more they’re able to work together to drive down operational costs. Typically, we’re seeing evidence showing that multiple high-performance building parts working together can shrink a building’s central mechanical systems, including heating, air-conditioning, and ventilation, by 10–20 per cent.

Another reason why businesses should go high performance is because it’s just the right thing to do. If you know you can do something better, why do it any other way?

Two key aspects of high-performance buildings are window treatments and indoor air quality. Let’s look at these in more detail.

Letting in the light

Fifty per cent of energy in a building is said to be gained or lost through the exterior façade, and yet building façades are typically made of poor materials because we not only need natural light to come in through them, but we also need to see out of them. There’s a paradox here that needs to be addressed.

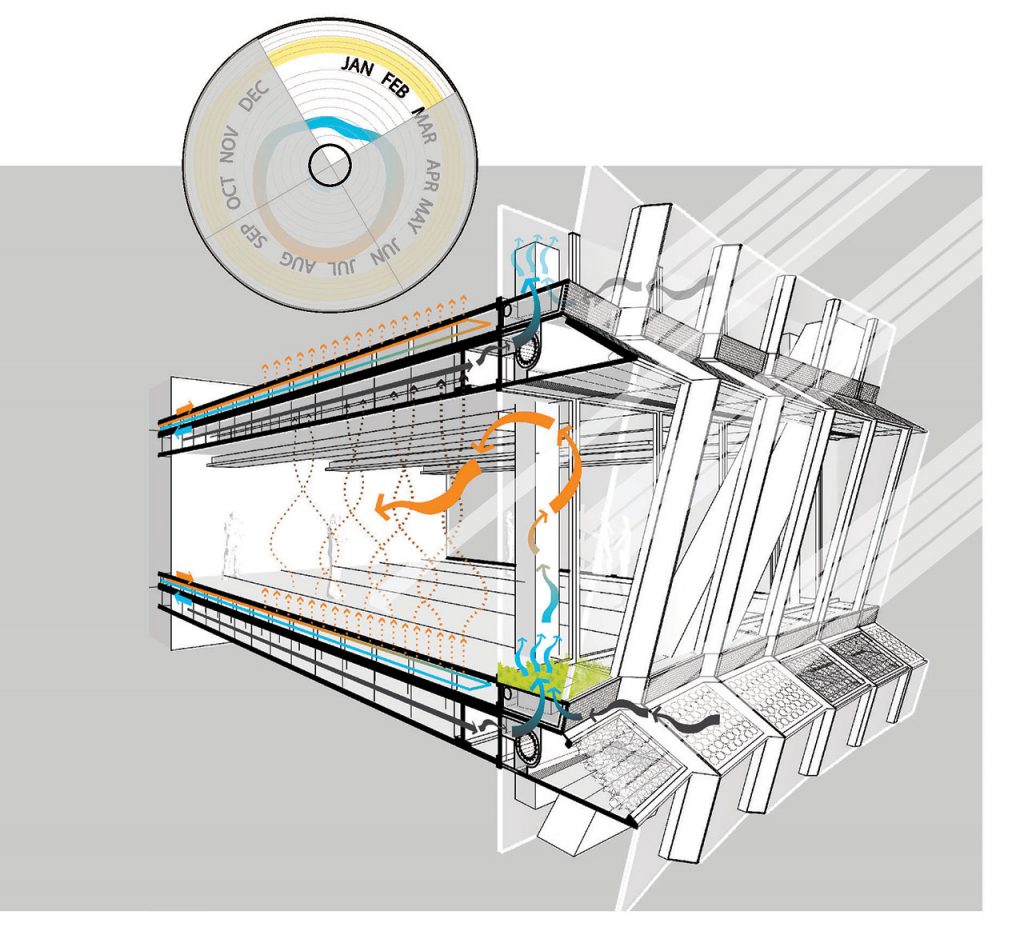

Glass is not a terrific thermal insulator, so you need to use as many tricks as possible to ensure occupants receive the right amount of light and heat; typically, we want light to come in and heat to stay out. We use computational analysis to check the direction of a building’s façade and global location to assess if, depending on the local climate and other environmental factors, we can use vertical, horizontal or other-shaped components on the outside of the building to regulate the light that comes in.

These can be static or automated and movable, via sensors, to reflect or allow in light according to the time of day. For example, in certain colder climates, and even some desert climates, light energy is needed mostly in the morning to preheat buildings.

Frit patterns, which are essentially etchings or printings on glass, can provide an interlayer between the sun and façade, by diffusing some of the light and reflecting it, helping to manage the energy that flows through the building.

Internal sensors that detect when the temperature inside is getting too hot, for example, can provide data to the building management system (BMS), which then automatically controls the internal temperature through air conditioning and/or window treatments — something we’re seeing more of and expect to become the norm in future high-performance building design. From the inside out, high-performance design

From the inside out, high-performance design considers the link between light and comfort — from how natural light affects the visual cortex through the rods and cones in our eyes, to how too much or too little light can impact on our natural body clocks, to ensure window treatments increase the amount of natural light that comes in but reduce glare and ensure an even light level.

Creating fresh air from within

Only in the past 100 years have we started spending more time indoors than outdoors. This is quite a big change in a comparatively short amount of time for evolution to contend with: high-performance buildings work to reduce our dependence on mechanical airconditioning systems and increase the exchange of outside air within.

In the 50s we typically designed buildings with massive floorplates, lots of artificial lighting and windows that we could open. Then, in the 70s, and largely due to the energy crisis, we realised that from an energy perspective, we needed to seal buildings to save money, trapping in and recycling the same air through mechanical air conditioning and heating systems. This led to buildings with deep floorplates and little or no natural light or ventilation, creating what is known as sick building syndrome, putting occupants at risk of respiratory infections, headaches, fatigue and decreased concentration.

Fresh air intake through mechanical systems, such as air conditioning, increase energy use, because you have to change the temperature and humidity level of the air before bringing it inside. In New York, for example, outside air is the right temperature and humidity for only for a few months of the year so it either has to be heated or cooled the rest of the time.

Air in our cities, certainly since the mid-60s, has become polluted because of increased traffic and other industrial pollutants, so the air outdoors can be worse than the air indoors. Policy developed to combat sick building syndrome requires us to take air from the outside and spend energy doing it, but in many cases the air is no longer considered healthy.

One solution is to create fresh air from within through large-scale phytoremediation; in other words, a large‑scale interior green wall. This is an incredibly innovative solution that uses plants to clean inside air of carbon dioxide and remove or lower toxins released from carpets and plastics (VOCs), releasing clean, oxygenated air back into the building.

Emerging science shows us that living and working in healthier buildings with better air quality leads to better executive functioning. But the difficult thing with advanced systems such as large-scale phytoremediation, is that they’re expensive to put in place. For this reason, it should be a showpiece, because that’s also where the value in this approach lies. The materials used in impressive lobbies are generally very expensive, and while expensive stone looks great, it doesn’t do anything: green walls look good, reduce energy use and improve health.

To be effective, you need to use many plants, so this approach may not seem cost effective in the traditional way that we calculate return-on-investment, and it can be difficult to quantify the benefits of having a closer connection to nature. But this shouldn’t be the focus of the story.

The story is that in our cities, there’s limited room to add biodiverse spaces outdoors. Whereas indoors, where we spend most of our time, there are plenty of opportunities. It comes back to doing the right thing, and working hard to see that innovative approaches like this become commonplace.