Successful program management and the importance of building a culture of collaboration

When it comes to infrastructure-led programs of major transformational change, establishing a shared operational culture is key. While the outcomes and vision must be clearly defined right at the start, AECOM’s Derval Cummins and Colm Tully propose also taking time to build desired behaviors from the bottom up.

When people talk about program management, they often focus on the processes rather than the people involved. But if you want a disparate group of people who aren’t used to working together to operate as one, the first step is establishing a culture of collaboration.

Human-centered design is key for adopting technology that is right for the program, rather than trying to retrofit a program around new technology. A common operating culture should be the platform on which the technology is built. Digital tools and systems should then be set up to process and share data from multiple sources in a single source of trustworthy, reliable, real-time information. The objective is to make it easier for designers, contractors, and supply chain to collaborate.

At AECOM, we deliver capital programs of critical national and international importance in aviation, roads and highways, rail, water, ports, power, energy and environmental clean-up, and have been key in shaping many of the major infrastructure programs and cities of today. That experience has taught us the importance of taking time to build a structure that brings the interests and actions of different stakeholders together right from the start.

There are three reasons why building an integrated culture is increasingly important

Complexity: Infrastructure programs are growing in scale and complexity, a reflection of the increasingly complex world they inhabit. This means working with a vast range of organizations and people at local, regional, national, and even global levels, many of them with competing interests. All the while you must consider specific political, geographical, social, cultural, linguistic, and economic climates.

Sustainability: Unlike other types of programs, capital programs create infrastructure that will exist for a very long time. To be sustainable, programs should be built to serve future as well as current generations, avoiding the need to expensively retrofit or rebuild. Endeavoring to provide intergenerational equity and a legacy through sustainable planning, design and construction is vitally important. This could be as simple as leaving space for new walkways or carriageways, or envisioning cycle routes in the skies.

Technology: At the same time, it’s important to keep pace with technological change. The objective should be to establish a connected system that brings consistency and value to an entire pipeline of work. From the very beginning, all the program information should be held in a common data environment (CDE) and kept up-to-date. Each team member across all disciplines should know how to navigate, store, and collect data within the CDE, including contractors or supply chain at each phase of the project. To properly prepare the teams, we implement a structured ‘fast start’ mobilization process, increasing the certainty of delivery on time and on budget.

Program management: five lessons learnt

While each program requires a bespoke solution, we have distilled five lessons from our experience in Integrated Client Partner roles on major infrastructure programs such as improving San Francisco’s water system (see case study, below).

1/Narrative: The first task should be to define the vision and program outcomes, informed by the client ethos, values and strategic objectives. This is turn will inform the scope of the capital program and its objectives. Creating a narrative to fit this will form a platform to develop the program and give it direction.

2/ Operational structure: A connected step is identifying, categorizing and engaging with the different stakeholders involved, with a view of establishing a ‘one team’ structure, where organizational badges are left at the door. The degree of control that the client requires is of course an important consideration when deciding on the most suitable structure, which should be shaped to suit. Due to complexity and duration of major infrastructure programs, which often span over five to ten years or more, collaboration across the supply chain is paramount to successfully ensure delivery.

3/Information management: The effective use of virtual design tools such as BIM (Building Information Modelling) during the design and construction stages can help all parties efficiently manage huge amounts of information and develop knowledge. BIM also means that building or logistical issues can be resolved before getting to site — avoiding potentially expensive retrofits or rebuilds. BIM model data, stored in the non-proprietary COBie (Construction Operations Building Information Exchange) format, can then be integrated with the client’s asset management software allowing a seamless transition of information to the operations and maintenance (O&M) team.

Managed well, data should flow freely between asset lifecycle phases through to O&M. Indeed, placing an emphasis on the O&M stage often leads to the gathering of better data early on which improves stakeholder interaction and engagement.

4/Embracing ambiguity, uncertainty, dynamism and risk: By their nature, major infrastructure programs often require cultural and organizational transformational change which involves a degree of uncertainty and risk. Working in such an environment requires dynamism — which should be encouraged by the organizational set-up of a program. Certainty will grow as the program progresses, but even so, we are living in a period of flux where technology and customer needs are constantly evolving. Flexibility is key and the Integrated Delivery Partner model provides flexibility in both capacity and capability of resource.

5/Sustainable accounting: It’s increasingly clear that traditional approaches to business case planning are failing to fully quantify impacts and risks, particularly when it comes to socioeconomic and environmental considerations over the long-term. In addition to financial reporting, we should take account of other metrics such as carbon. Where possible, we recommend a ‘six capitals’ approach, putting a monetary value on manufacturing, human, social, intellectual, natural and financial capital.

Once program management was about seeking delivery of an objective through a collection of projects — with the knowledge that the end point was uncertain. With so many variables involved there was a recognition that achieving the desired objective could not be guaranteed. That was not necessarily a bad thing: the skilled program manager would look to exceed expectations, where possible. Today, however, programs are all about certainty. Objectives need to be ultimately defined before anyone says yes; business tools offer ways to measure precisely all the known ingredients. All this achieves is constraining programs to what we can predict. That means many fall short.

Ultimately, it is people who make programs work and success depends on getting the most out of them. The first step is to agree on a clear vision and define the project outcomes to create a compelling narrative that aligns strategies and actions, providing a platform for a ‘one team’ approach. Success relies on communicating the narrative to influence behaviors from the bottom up.

In addition, to be sustainable more thought has to be given to the evolution of a program, allowing for a range of possible future uses. Our integrated delivery model is designed to address the entire program lifecycle, creating legacies for generations to come.

Case study: Water System Improvement Program (WSIP), San Francisco

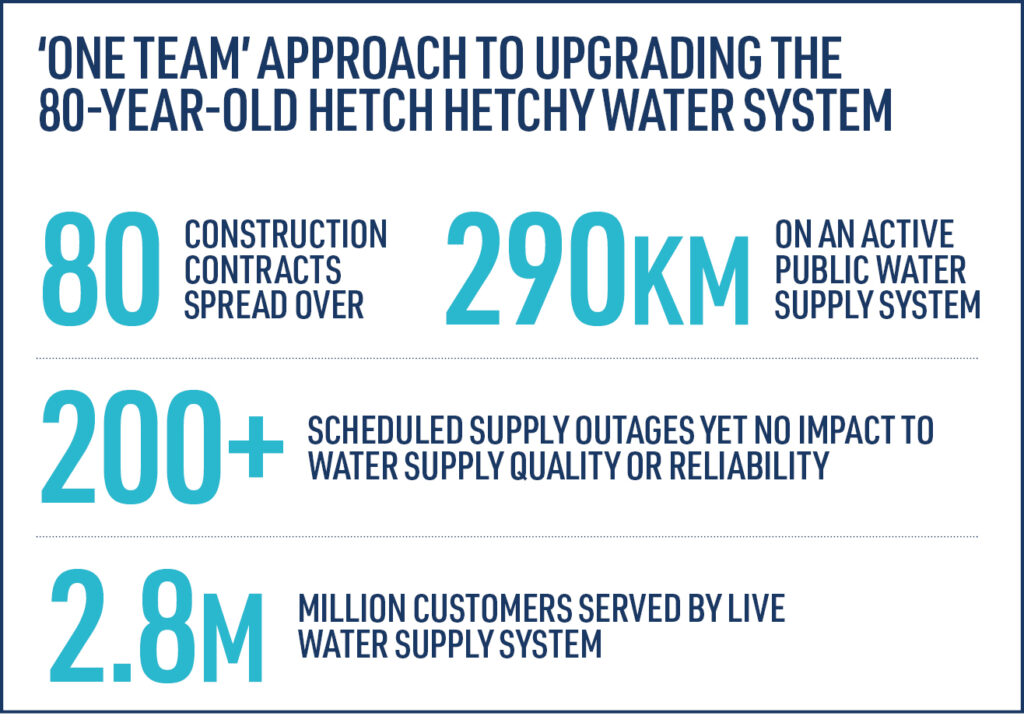

As Integrated Client Partner to the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC), we implemented a ‘one team’ approach to upgrading the 80-year-old Hetch Hetchy water system. This collaborative approach enabled WISP to be delivered safely on time, on budget and with no disruption to the service for over 2.7 million customers in San Francisco and the Bay Area.

As the program construction manager, our team was responsible for overseeing and supporting the uniform and consistent application of the construction phase management plans, processes and procedures. As part of this we were responsible for delivering over 80 construction contracts spread over 290 km on an active public water supply system. This included construction contract administration, technical and quality assurance, cost and schedule control, supplier quality surveillance, risk management, formal partnering coordination, training and construction safety management. For the during of the program, we co-located with the SFPUC.

With over 200 scheduled supply outages on a live water supply system serving 2.8 million customers, there was no room for error. Maintaining communication, coordination and collaboration consistently across all processes and procedures was essential. Using Construction Management Information System (CMIS) software, our team maintained a detailed master program schedule which was continuously updated from project inputs. We used this information to lead monthly coordination meetings between system operators and all regional and program level management.

Success was demonstrated by the following results at completion of construction:

• No stoppages of construction work

• No claims litigated

• Over 9,300,000 construction hours with zero fatalities and low reportable incidents below national average.

• No impact to water supply quality or reliability over 200 shutdowns

• No public lawsuits or protests in an area known for activism

• Numerous national awards and recognition for excellence.