Cities underground

When we talk about subterranean development, people most often think of underground railways or deep caverns in rock for storage of oil (pictured below) or generation of hydropower. But we build places for people underground as well—basements just below grade, deeper mined spaces, and the pedestrian linkages between these spaces and underground rail. As cities run out of room and seek low-energy solutions, down is a direction that more of them are looking. Above image courtesy of JTC.

The classic examples of interconnecting basements are Montreal, Canada and Helsinki, Finland, where there are multiple connections between buildings and subways at three levels below the street. Deeper mined space is typified in Norway and Sweden, where underground caverns have been mined and are used for a variety of purposes such as swimming pools, hockey pitches, and at Gjovik a massive multipurpose sports and concert hall for thousands of people (pictured below).

There are two prime reasons for going below ground—the high cost of land above ground in congested city centres, and the benefit of ambient temperature. The earth’s temperature remains constant below ground. Cold-winter cites like Montreal, Toronto, and Helsinki take advantage of this to heat buildings. More recently, cities in the Middle East are using the same effect to keep them cool.

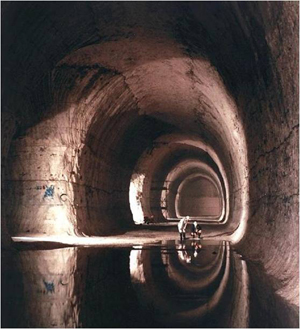

In big cities the space below roads is already congested with utilities and subways, and basements have been developed independently for different purposes and at different levels. Retrofitting—making new connections of old basements—requires planning and coordination between properties and property owners and often involves expensive construction or demolition and reconstruction. In new areas such as Marina South in Singapore, newly formed land has been subject to master planning and the new area includes requirements for systematic connections below ground and across streets. Mining big caverns out of competent rock is a straightforward process in itself, but getting access to the rock can be difficult depending on the choice of location. Excavation pictured below.

Interconnection of basements is catching on fast. In Helsinki and Montreal there are extensive networks below ground. In my territory, Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Singapore have joined in. Generally in big developing cities, multi-level basements are becoming popular for supermarkets as well as for car parking and connections to underground railways. Pictured below: basement connected to transit in Singapore.

Geotechnical engineers get involved in studies for site selection, site investigation, design of the underground structures, and supervision of construction. I am involved currently with railway developments in Kolkata Chennai, Mumbai, Delhi, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok and proposals in Australia and New Zealand. We have completed the preliminary design and are commencing detailed design for caverns to house sewage treatment plant for a population of 800,000 close to our offices at Sha Tin, Hong Kong. We have completed preliminary design for underground warehousing and an IT Centre in Singapore. This year I was invited to advise the Singapore Urban Renewal Authority on integrating underground development in their strategic planning for the next 50 years.

Urban space is running out as city streets become super-congested and buildings rise higher and higher. There is plenty of room below ground if one creates and makes use of it. There are problems with ownership and land rights in some countries and these need to be resolved, but the time has come for most city governments to seriously consider underground development.

John Endicott is executive director, geotechnical engineering for AECOM in Hong Kong.

John Endicott is executive director, geotechnical engineering for AECOM in Hong Kong.