#CoolJobs: I get paid to climb trees and save bats

From dormouse monitoring, sediment sampling and pitfall trapping for great crested newts to taking National Vegetation Classification surveys of Royal Naval Air Service runways and camera surveys of urban badgers, the sheer variety of work within my cool job as an ecologist keeps me on my toes and makes every day rewarding.

Bat surveys are a large and fascinating part of my work at AECOM. Bats are notoriously harder to survey than other protected species as they are small, airborne and nocturnal. In addition, around three quarters of bat species frequently roost in trees.

My interest in how bats use trees was piqued after a training course on the subject. The course increased my curiosity to understand these features more thoroughly, especially since a key part of the course was aimed at making people aware that bats may only use an individual tree roost for two percent of the year. Therefore, the chances of actually finding a bat in a tree roost are extremely slim. Consequently, other features to consider are the habitat and wider environment, as well as the roost feature itself, including characteristics such as internal structure, texture and colouring. Gaining a better understanding of the types of roosts that bats use can influence impact assessments, the mitigation methods employed and improve the suitability of replacement roosts.

In addition, bats play a significant role in the environment, which is why all native species of bats are strictly protected under law in the U.K. and Europe. There are 17 species of bats breeding in the U.K., and they are key indicators of biodiversity and ecosystem health as they provide a number of ecosystem services. More than 500 plant species rely solely on bats for pollination (a process known as chiropterophily). Furthermore, bats act as an excellent pest control. The common pipistrelle bats can consume more than 3,000 gnats (flies such as mosquitoes) in one night.

Charlie works to obtain the highest anchor point in a pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) before checking potential bat roost features.

Charlie works to obtain the highest anchor point in a pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) before checking potential bat roost features.

My love affair with tree climbing started in February of this year when my line manager, Paul Gregory, asked if I wanted to train for my tree climbing licence to assist AECOM with its work on the High Speed 2 (HS2) project, a major high-speed rail line development between London and Birmingham. I jumped at the chance as I’ve always loved climbing, heights, and anything active and outdoorsy.

The training was a week-long course on the grounds of Saltram House, a Georgian National Trust property — an idyllic place to learn due to its stunning historic parkland views across the River Plym into the city. The course involved lots of knot tying, “thrusting” up trees, spiking, untangling ropes, climbing to 20 metres, branch walking to increase comfort levels in the canopy and getting frustrated at missing my first anchor point due to my pitiful throwing skills. With each climb, I felt less nervous and the different knots became easier to tie. It was exhausting as well as exhilarating.

Once I passed my tree climbing assessment, it was time to put these new skills to use to investigate potential bat roost features. I was provided with an abundance of opportunity to do this on the HS2 project. I am lucky enough to have had the chance to be involved in this survey work, to reduce the environmental impacts of this high-profile scheme, and to play a part in transforming rail travel in Britain.

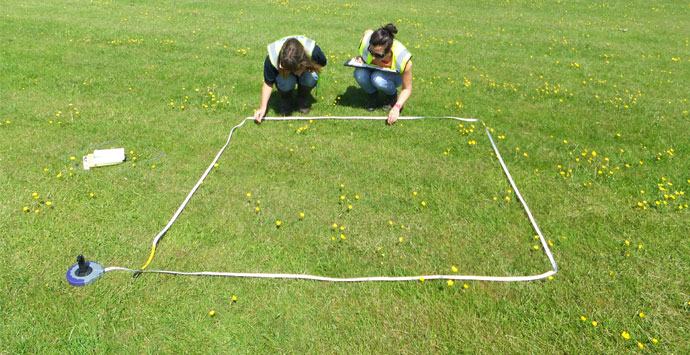

National Vegetation Classification survey quadrat of an airfield grassland.

National Vegetation Classification survey quadrat of an airfield grassland.

The ecological surveys on this project have involved assessing woodlands, which will be impacted by the scheme. Trees are first checked from the ground, and any potential bat roost features are noted for the attention of the tree-climbing team, and that’s where I come in.

Checking a potential bat roost feature involves climbing a tree until you have an anchor point above the feature of interest. You can then hang down on a rope and investigate the feature, using torches and endoscopes. From the ground, the bat roost potential of a tree can be very tricky to determine — especially when the leaves are out on the trees. Climbing helps us get better answers about bats and their habitats, which helps the project as well as the bats.

The most exciting moment of my tree-climbing career so far has been the discovery of a female Brown Long-Eared bat roosting in a trunk cavity of an ash tree — definitely worth all of the blisters!

A brown long-eared (Plecotus auritus) bat.

A brown long-eared (Plecotus auritus) bat.

Since I became a qualified tree climber, I have had the chance to work alongside some of the more senior and experienced AECOM tree climbers. This has been a really valuable experience as I have picked up lots of handy hints and tips — from new ways to tie knots to new, less strenuous, foot-locking techniques. I still rely heavily on my throw bag, but it’s getting easier.

Charlie Bellamy is an ecological consultant working out of AECOM’s Plymouth office in southwest England. She has a degree in zoology and has written a Master’s degree thesis on the use of birds as biodiversity indictors of climatic change at Durham University. She is also licensed to work with hazel dormouse and bats. Charlie is a full member of the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management and outside of work is an active committee member on various local wildlife groups and a volunteer hedgehog and bat carer.

Charlie Bellamy is an ecological consultant working out of AECOM’s Plymouth office in southwest England. She has a degree in zoology and has written a Master’s degree thesis on the use of birds as biodiversity indictors of climatic change at Durham University. She is also licensed to work with hazel dormouse and bats. Charlie is a full member of the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management and outside of work is an active committee member on various local wildlife groups and a volunteer hedgehog and bat carer.

LinkedIn: Charlie Bellamy