To compete, connect

Mumbai, India. ©AECOM Photo By David Lloyd.

E.M. Forster’s novel, Howards End, examines social relations in turn-of-the-century England. “Only connect! … Live in fragments no longer” is the guiding exhortation of the novel; Forster encourages us to bring our ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ lives together. While he is speaking to the lives and times of his main characters, he might just as well be referring the challenges faced by contemporary cities.

Today, we are living in a more fluid world than anyone has ever known. Through the developments of the internet, social media, and long-haul aviation, we experience an increasingly free and fast movement of ideas, people and goods. For the developed city, this creates a tension between its original inner life — the cultural norms and rhythms that defined it for centuries — and the altogether new demands of an outward-looking and globally competitive economy. If we live in a European or North American city that has failed to grow long-haul air links or globally relevant specializations, then we’ve seen much of our industrial activity moved overseas. Money drains from our communities; capital flies in and out; middle-class jobs turn into low-level service duties. Along with that, we also experience the weakening of the cultural institutions they once upheld.

Dubai, United Arab Emirates. ©AECOM Photo By David Lloyd.

However if we live in a developing urban economy, we often experience the reverse. If we are fortunate to be part of a city that has managed to specialize within the flow of global trade, and has invested in aviation capacity in particular, then we benefit from comparative advantages; we are the integrators of the vast global supply chains that bring together the miscellaneous inputs from other contributing cities. We are often able to flee grinding rural poverty, have access to better education, healthcare, and social equality. Through economic development we see gradual improvements in the very institutions — government, banks, schools, grocers — that weakening western cities are mourning.

But there is something else happening too. At a global scale, the globally relevant cities now have more in common with cities thousands of kilometers away than they do with their respective hinterlands a few hundred or just a few dozen kilometers away.

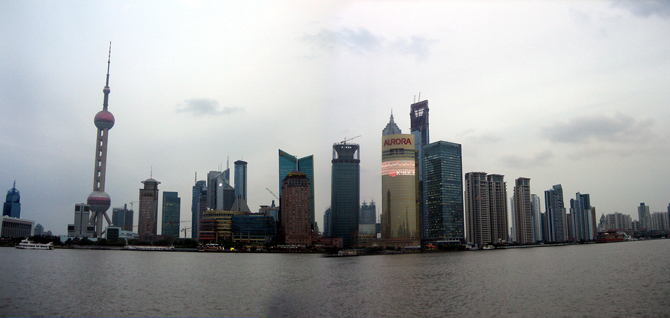

Shanghai, China. Photo by Ying Zhang.

These global cities are aggregating with one another as they progressively share financial, material, human, and intellectual capital. Just as the economies and demographics of New York and London have grown to resemble each other over the past generation, Shanghai not only increasingly resembles Singapore, but also Sydney and Dubai. At a local scale, however, these same cities are also disaggregating, pulling away from their respective hinterlands, and often from their own natural characters. The populations of some towns in Pennsylvania barely resemble their neighboring counterparts in New York City, just as Stoke-on-Trent has relatively little to do with nearby London, and the heterogeneity of London today would have been unrecognizable a century ago.

London, UK. ©AECOM Photo By David Lloyd.

What do we make of all this? In a globalizing world, cities are becoming more important and relevant than nations. Global cities will continue to integrate virtually all the world’s innovation and wealth. In this world, the largest, best-connected cities will win, but often at the expense of smaller, less dense, and less well-linked cities and their dependent regions. These lesser cities, for their part, will need to fight very hard to become more relevant or they will fail. In particular, they will need to balance their natural introspection with a genuine and profound desire to integrate with the rest of the world through better governance, more resilient levels of urban density, improvements in transport infrastructure, and betterment of civic space.

History is full of great cities that declined because they turned too far inward and failed to develop outward-facing connectivity. The Chinese city now known as Xi’an was by far the largest and most prosperous city in the world during the Tang dynasty. In the early 1800s, 40 percent of the world’s trade passed through Liverpool, and it was unthinkable that it would ever become but a footnote in global rankings. Think of the relative collapse of Alexandria in Egypt, Coimbra in Portugal, or Thessaloniki in Greece — all of them were dominant cities in their primes yet hardly register today. Even London could lose its global edge to ambitious cities like Amsterdam if it can’t manage to expand its aviation-hub capacity. Cities must aggressively invest in globally-scaled physical infrastructure to trade and exchange effectively with their worldwide peers: face outwards or die.

New York City, United States. Photo by Erika Matthias.

On the other hand, even the greatest global cities will increasingly need to reconcile their broad and homogenizing tendencies with a greater self-awareness of what makes them special in the first place — or risk losing the comparative advantage of their unique identity. Contemporary cities must reconcile their outer and inner lives to thrive. E.M. Forster’s exhortation remains true: engage the world, but also remain self-aware. Only then do we truly connect.