Debunking the myth that Passivhaus is costly to achieve

There is an assumption that building to Passivhaus standards leads to an uplift in capital costs. Our research shows otherwise, say sustainability experts Evangelia Mitsiakou and David Cheshire.

It is hard to talk about net-zero carbon buildings without considering Passivhaus, and it is difficult to discuss Passivhaus without there being a sharp intake of breath and fears of cost increases. But does Passivhaus really cost more money?

Passivhaus versus capital cost

Passivhaus is a building standard and certification system that sets operational energy and occupant comfort performance criteria. Despite the name, Passivhaus can be applied to all building types – haus means building in German, not house – indeed there are plenty of large, non-domestic buildings that are applying the standard.

In the case of net-zero buildings, the emphasis is on reducing energy demand as far as possible so that a higher proportion can be met through onsite renewable energy generation on site (e.g. photovoltaics) and on the fact that the nation’s energy demands will increasingly be met by renewables, such as wind farms. The UK Green Building Council (UKGBC) has already set energy demand targets for offices and will be setting targets for other building types. The London Energy Transformation Initiative (LETI) guidance has set a 55kWh/m2/year figure for buildings – a seriously challenging target.

Passivhaus, however, sets maximum performance criteria for space heating and cooling demand, air permeability, overheating and primary energy demand. The Passivhaus heat demand target of <15kWh/m2/year is less than a fifth of a typical non-domestic building’s demand, which radically reduces the overall energy use and associated carbon emissions compared to the conventional design approach. There is a rigorous procedure for certification and stringent requirements to prove that the building is built as designed. This has helped to close the much reported ‘performance gap’ as research shows that Passivhaus buildings are delivering on their design promises.

Crucially, proponents of Passivhaus argue that there is no capital cost uplift associated with applying the standard, as long as the principles drive the design from the very start.

To achieve Passivhaus standards within budget, cost savings must be sought elsewhere, such as creating compact built forms and simplifying the architectural detailing. Furthermore, creating an integrated design that avoid thermal bridges reduces heat loss. This means it is easier to meet the stringent insulation standards and that most of the heat demand is met by internal heat gains from people and equipment. As a result, the heating plant is far smaller, and the cost savings can then be spent on triple glazing, openable windows and highly efficient ventilation systems.

Our research

That’s what the Passivhaus experts say, but how do we verify just how much Passivhaus costs? It is difficult to nail down the capital cost uplift for Passivhaus as each building is different and it is difficult to isolate the changes that relate to Passivhaus from the other differences between each building. So how do we get a real handle on capital cost uplifts of Passivhaus?

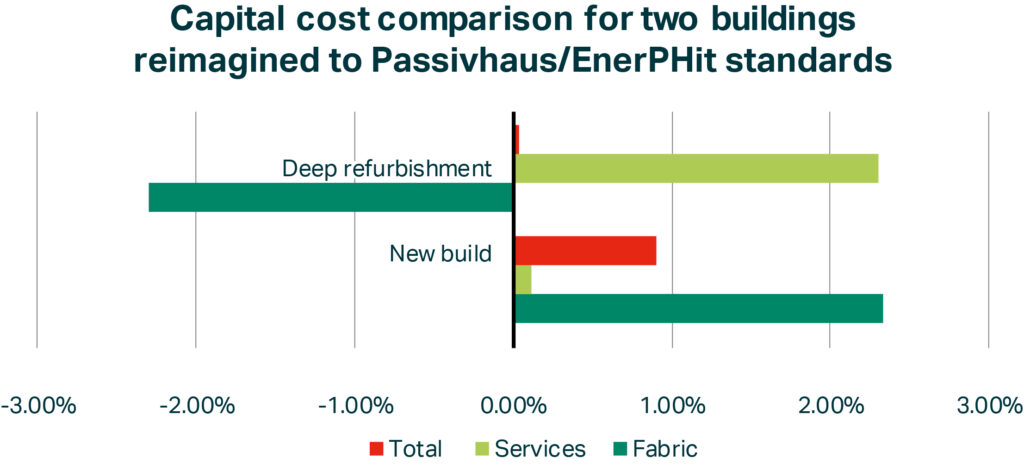

We explored this question in some recent AECOM-led research for University College London (UCL) Estates. We assembled a multi-disciplinary team consisting of an experienced Passivhaus architect, a Passivhaus-trained building services engineer and cost consultants from AECOM with experience of costing Passivhaus schemes. To get a clearer picture of the changes in capital cost, we took two recently completed buildings that were designed to current regulation and policy standards and ‘reimagined’ them as if they had been designed using Passivhaus principles by altering the building fabric and the MEP design. We applied the basic principles that make up a Passivhaus building – i.e. triple glazing, Mechanical Ventilation Heat Recovery (MVHR) etc. – and then estimated the capital cost implications of each of the changes for each building. The third and final step was to estimate the operational costs and prepare comparison matrices showing the relative life cycle benefits for each measure.

The results showed that the capital costs uplifts were far lower than commonly assumed. The overall capital cost uplift was only 0.9 per cent and 0.04 per cent for a new build and a deep refurbishment respectively (see breakdown in Figure 1). This contrasts strongly with the 10-15 per cent uplift commonly quoted and shows that a relatively small cost can yield huge energy demand and carbon savings. It also puts the idea of offsetting the energy demand through on-site generation within touching distance.

Following the research, UCL Estates has updated its standards to place a much greater emphasis on reducing energy demand as part of its approach to net-zero carbon buildings. Ben Stubbs, Head of Sustainability at UCL Estates commented: “Our work with AECOM provided reassurance that implementing Passivhaus principles doesn’t necessarily cost more for new buildings and can even result in significant savings when viewed in life cycle terms.”

Passivhaus provides a rigorous approach to radically cutting energy demand, enabling net zero buildings. Furthermore, because Passivhaus is actually closing the performance gap, it is a standard that truly delivers net zero carbon buildings.

This research was undertaken by the following AECOM experts in collaboration with UCL:

- Dave Cheshire, Sustainability, Project Director

- Evangelia Mitsiakou, Architect and Passivhaus Designer, Project Manager

- Rebecca Lindridge, Associate, Cost Consultant

- Florentino Bercasio, Director, Cost Management

- Chris Bicknell, Asset Advisory, Director, Life Cycle Cost Consultant