The carbon and business case for choosing refurbishment over new build

New buildings have been portrayed as a symbol of progress and a thriving economy, but in an increasingly resource-constrained world, should we be so quick to demolish and rebuild? AECOM’s Dave Cheshire and Mike Burton look at how analysis and early scenario planning can create a business case for retaining buildings, cherishing our architectural heritage and helping the industry reduce carbon emissions.

The built environment demands around 40 per cent of the world’s extracted materials while waste from demolition and construction represents the largest single waste stream in many countries.

Together, building and construction are responsible for 39 per cent of all carbon emissions in the world, with operational emissions (from energy used to heat, cool and light buildings) accounting for 28 per cent. The remaining 11 per cent comes from embodied carbon emissions, or upfront carbon that is associated with materials and construction processes throughout the whole building lifecycle.

To meet the UK government’s commitment to reduce net carbon emissions to zero by 2050, the building industry has a big role to play, requiring radical cuts in emissions from construction and operation.

In this article we examine the environmental case for refurbishment, and how that is guiding policy change. Historically, there have been powerful incentives – cultural and financial – favouring new build, but this is changing – and the business case for refurb and rebuild is growing.

Embodied versus operational

The perception is that building new will radically reduce carbon emissions in operation compared to an existing building. However, those savings will only be achieved in the future and even when operational emissions are reduced, constructing a new building means paying a heavy upfront toll in terms of carbon emissions from the extraction of raw materials, transport and construction.

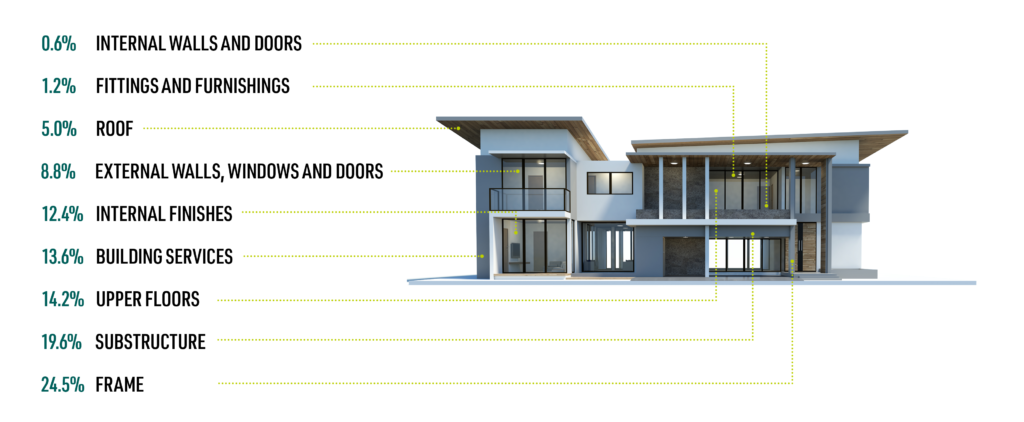

In contrast, a deep refurbishment of an existing building can also cut operational carbon emissions — without the emissions associated with building new. Embodied carbon covers the total emissions arising from constructing a new building and its end of life. Figure 1 shows that over 60 per cent of embodied carbon emissions are associated with the sub structure, frame, upper floors and roof of a building. A deep refurbishment should retain these elements, meaning on average, the carbon footprint of a refurbished building is half that of the newly-built replacement.

The environmental case for refurbishment

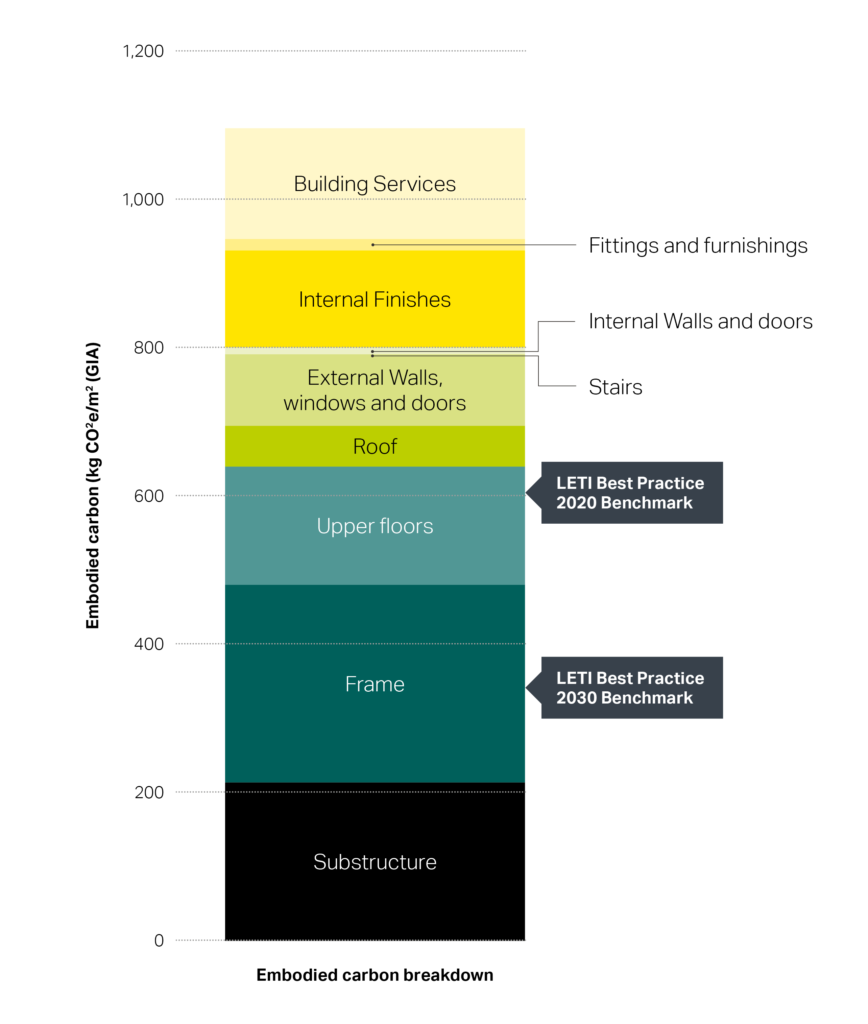

Research by the London Energy Transformation Initiative (LETI), a network of over 200 built environment professionals, shows that buildings must reduce their carbon footprint or embodied carbon emissions in the future if we are to achieve net zero. LETI has proposed an embodied carbon budget of 600 kgCO2e/m2, which is a tough call given that a typical commercial building would have 1,000 to 1,500 kgCO2e/m2. With a new building, basements and structural frames require tonnes of concrete, steel and aluminium which account for about a third of the embodied carbon as shown in Figure 2.

A deep refurbishment can retain the sub-structure and structure and still provide excellent fabric performance – as judged by retrofit-specific standards such as Enerphit. By choosing the right fabric, some buildings can reduce heat demand and provide equivalent or better lighting and ventilation standards as a new building. Of course, not all buildings will be suitable for net zero carbon retrofit, but with ingenuity a lot more can be done than you might think. Key considerations will include massing (how the building looks in terms of shape or mass), floor-to-ceiling heights, depth of floor plate, and the positioning and size of cores. Replacing the building fabric and the building services can make a huge difference.

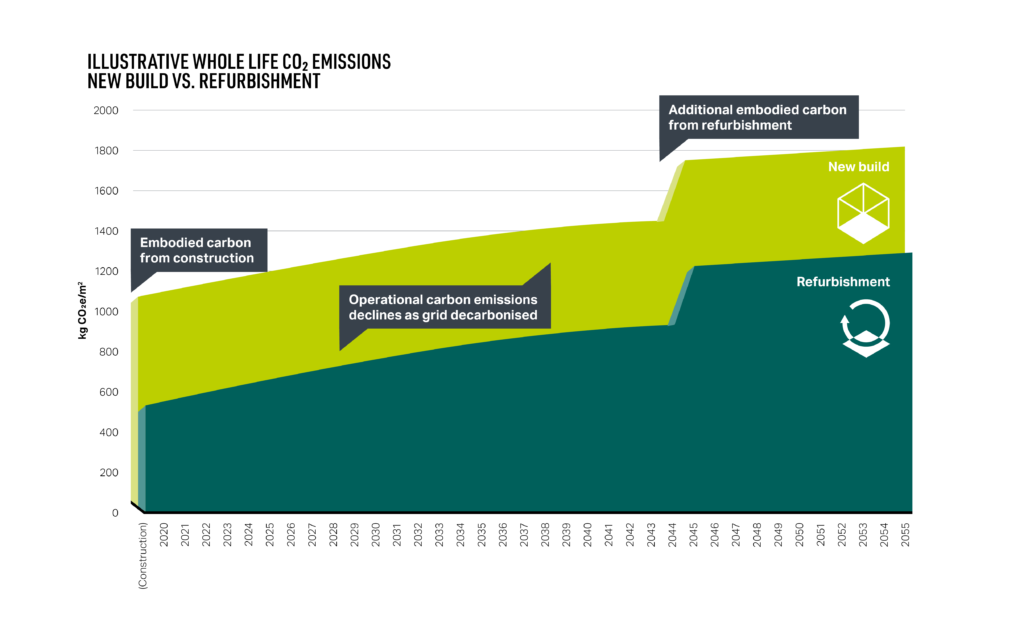

Because of the significant embodied carbon impacts of new buildings, any savings from operational energy use would not compensate for the initial emissions, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 assumes an initial embodied carbon for new build based on AECOM research alongside a refurbishment scenario that retains the sub-structure and structure of an existing building. There is a further refurbishment after 25 years that covers the building services and interior fit-out. The operational carbon emissions are adjusted using the projected carbon emission factors for electricity which can be seen by the gradual decline in the operational emissions over time.

The graph shows clearly how many emissions are front-loaded with new buildings, whose environmental credentials are based on promises of lower emissions in the future. To reduce the risks associated with climate change, emissions need to be cut now.

Staying ahead of policy change

If the best way to achieve the net zero carbon targets is to refurbish whenever possible, why is this not in legislation and planning policy? Things seem to be edging in that direction, but there are some major impediments.

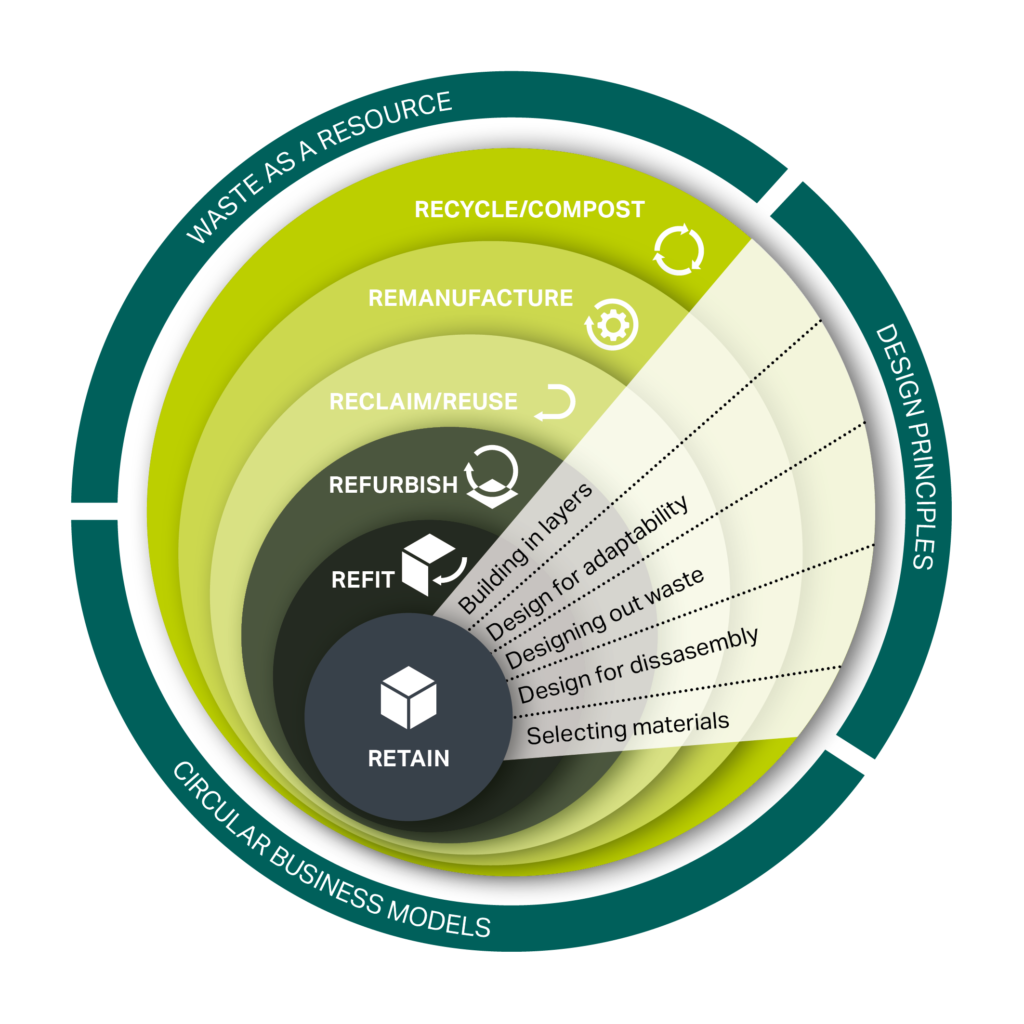

In its draft London Plan, the Greater London Authority has set out design principles for projects that prioritise retention and refurbishment (see Figure 4). When adopted, the city region’s statutory spatial development strategy will require a Circular Economy Statement demonstrating how products and materials will be recovered and re-used for all referable projects, as well as a Whole Life Carbon assessment, covering embodied and operational emissions. This is reinforced by the Circular Economy Statement guidance that questions whether there is an existing building on site and whether that building can be retained.

The London Plan requirement for Whole Life Carbon assessment is now included in the Energy Strategy Guidance to encourage applicants to consider the embodied carbon impacts as well as the operational energy performance of proposed new developments.

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) also recently launched a Retrofit First campaign, championing the reuse of buildings. This has highlighted the long-running problem of a 20 per cent VAT levy on refurbishments as opposed to 0-5 per cent on new build. This creates an incentive to build new instead of refurbishing. RIBA is campaigning to cut the tax to 5 per cent for refurbishments to help to level the playing field.

These are steps in the right direction, but when sites are being procured and when an organisation is looking for more space the incentives to favour new build are still manifold. This will change if policy pushes it in the other direction.

The business case

As well as the carbon incentives, there are other powerful arguments for retaining buildings in our towns and cities. Early option appraisal and planning, together with data analysis can help guide decisions, often before a site is acquired.

With an existing building, there is a lower level of risk involved and the refurbishment programme can be much shorter. New build can take five years from inception to hitting the market, by which time workplace practices and technology expectations will have changed. It is becoming increasingly important to get buildings to market quicker. For example, the Crown Estate’s BREEAM Outstanding refurbishment project on 7 Air Street took only one and a half years from inception to completion but would have taken over three years to build new.

Tenants and occupiers are also becoming more discerning about the buildings they occupy and procure. Awareness of the climate crisis is forcing many to assess their choices and may well drive demand for buildings with lower embodied carbon as well as operational energy. Organisations that own property portfolios are certainly under pressure from the policy agenda and from public perception to show radical reductions in emissions and constructing a new building will reverse their downward trajectory towards net zero and incur additional costs to pay into offset funds.

Refurbishments can look as modern as the freshest of new builds. Organisations such as Derwent London have built their reputation on high quality refurbishments including The Tea Building in East London and the Johnson Building in Central London and have been instrumental in driving awareness of the benefits of cherishing and pumping new life into existing buildings and streetscapes.

We know that new buildings can inspire, but so can refurbished ones. In the future, we are likely to see developers actively looking for buildings that are ripe for refurbishment rather than development. If we’re to achieve our net zero ambitions, it is the only way.