Learning from Hong Kong

I have recently found myself looking to what I consider my second home – Hong Kong – for a fairly straightforward formula of how our increasingly affluent planet needs to quickly learn to consume less: intensifying urbanization, and a specific type of urbanization that is very dense, compact and well-connected, which builds in strong efficiencies while significantly reducing its carbon footprint and reliance on many energy-intensive assets.

In Hong Kong, largely by accident, urban planning policy has created a low CO2e model. This is a dense place. According to the Hong Kong government, there are 6,620 persons per km2, with density reaching up to 56,200/km2 in one district. Hong Kong’s seven million plus people are packed into just 25% of its land area (1,104 km2) with 40% of land remaining protected green space. Hong Kong achieves this by being highly vertical (thanks to more than 7,400 skyscrapers), and the average Hongkonger lives small: the average size of a new home there is 484 ft2. Compare that with the US, where the average size of a new home is nearly four times larger: 2,164 ft2

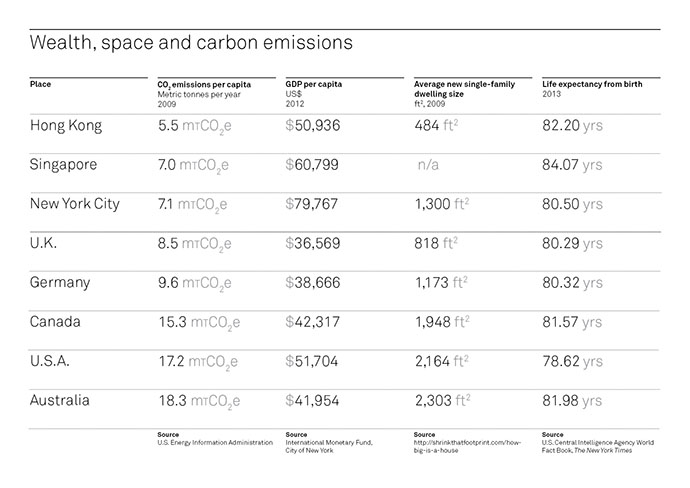

Hongkongers may live small, but they are also comparatively wealthy and live longer. GDP per capita is roughly the same between Hong Kong and the US, and a Hongkonger manages to live more than four years longer. The table below illustrates that you can be affluent and live on a lot less. There is a very strong correlation between new home size and carbon emissions.

Despite being at a similar economic level to a typical American, a typical Hongkonger’s carbon footprint is 68% less than that American’s. When one assesses home size, the percentage disparity is even more pronounced – the size of a new home in Hong Kong is 78% smaller than an American one.

New York, one of the densest places in America, is a domestic outlier in terms of CO2e per capita, average new single family home size, and proportion of the population that uses public transport. A New Yorker’s carbon footprint is 59% less than an average American’s; his home is on average 40% smaller; and the share of New Yorkers using public transport to get to work is more than 13 times the average for the wider country – all this despite the fact that a New Yorker is on average much wealthier than the typical American and lives longer.

The lesson here is that this model of urbanization—based on a smaller home size that consumes less energy and can accommodate a population much closer together and to their places of employment and leisure—significantly lowers individual carbon footprint without burdening individual economic level and quality of life (in fact quite the opposite).

The Hong Kong pattern of urbanization is further underpinned by significant investment in a connected public transport system that is based on the idea of overlapping uses spatially. The expansion of Hong Kong’s urban footprint in the last several decades has been intimately tied to transit-oriented development. As its population expanded from the original urban core of Hong Kong Island and Kowloon, new urbanization in outlying areas of the territory has followed a linear pattern that is set by the rail tracks laid down by Hong Kong’s MTR Corporation, the primary rail provider. Each of these new towns is very efficiently tied to the rest of the city through a system that results in more than 90% of the population using public transport every day. Admittedly, the character of Hong Kong’s urban form – something that looks a bit like a messier version of the Corbusian ideal – is not to everyone’s taste, but it no doubt is a pretty efficient way of ensuring that wealthy, urbanizing societies keep their carbon emissions down.

Daniel Elsea is creative director for AECOM’s Buildings + Places group, is the co-author of the forthcoming book “Jigsaw City: AECOM and the Asian New Town Now,” and is currently a post-graduate in sustainable urban development at the University of Oxford.

Daniel Elsea is creative director for AECOM’s Buildings + Places group, is the co-author of the forthcoming book “Jigsaw City: AECOM and the Asian New Town Now,” and is currently a post-graduate in sustainable urban development at the University of Oxford.