The new draft London Plan

It has been a tough year for London.

From the shocking acts of terror on our streets this summer, to the harrowing Grenfell tragedy, London’s resilience has been thoroughly tested during 2017.

As Londoners, we are becoming increasingly aware that the air we breathe is toxic and our economy is under threat from Brexit uncertainty. Meanwhile we remain in the grip of an affordable housing crisis.

Sadiq Khan has a tough agenda in terms of planning and development issues and has been criticised by some as being slow to act. Housing starts have fallen in 2017 and the mayor has appeared to keep his distance from the development industry unlike predecessors Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson. He has, however, been overseeing a number of strategies published this year, culminating in the eagerly awaited draft London Plan published on 29 November 2017—18 months after his election.

At 524 pages, the new plan goes into significantly more detail than previous versions, with a range of new policies to ensure more inclusive growth in line with Mayor Khan’s commitment to make a city for everyone.

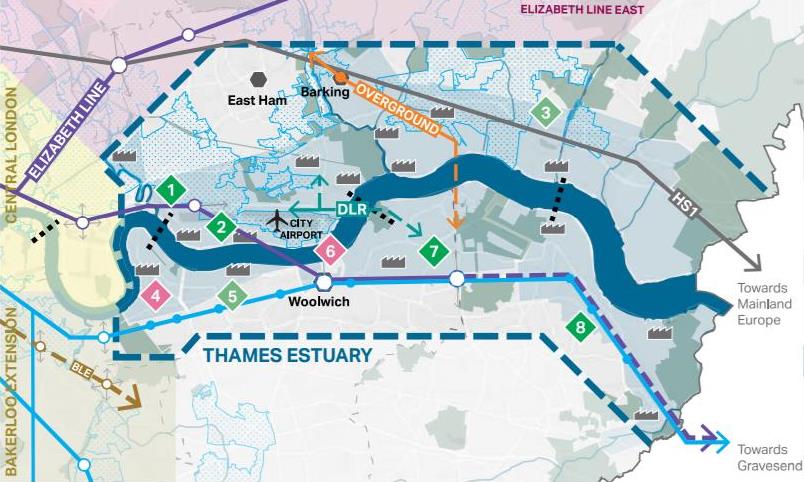

The mayor is looking to tackle congestion and air pollution through the “Healthy Streets” initiative outlined in his draft Transport Strategy, with support for the next generation of transit projects. Meanwhile, the mayor’s ambitious Environment Strategy proposes a zero carbon city by 2050—and working toward becoming the world’s first national park city—greener and less dominated by traffic. The launch of his “Good Growth” advocates is also a welcome move, placing high-quality design at the heart of the planning agenda and moving away from a purely quantitative approach to density definition.

Many of these strategies look a long way into the future, but Khan’s focus will be May 2020, when he is up for re-election and will need to have shown results. And of course, the most pressing issue for the mayor is housing and its impact on London’s long-term social and economic resilience, as more and more are priced out of the city.

Khan’s housing strategy, published in September, outlines a number of ideas to tackle the crisis, including a greater variety of providers, more social housing, more land for housing and support for modern methods of construction. The draft London Plan places renewed emphasis on maximising affordable housing at 50 percent and a significant increase in annual housing targets—66,000 new homes a year. The challenge for policy makers will be having the delivery tools and resources to more than double the current annual build rate of 29,000.

Despite this big challenge, London’s greenbelt remains sacrosanct, with the main focus on brownfield land—including often constrained public-sector sites. This means development at much greater densities than London has ever seen, which will inevitably mean taller buildings across the city and increased pressure on London’s precious green space.

But will this solve the housing crisis? Will denser, taller development be the answer—particularly in light of the Grenfell Inquiry due this winter? And how can development take place in the London Plan’s many “Opportunity Areas” to the true benefit of Londoners, delivering the required affordable housing, community facilities and high-quality environments the city deserves while meeting development viability requirements? Time will tell, and the clock is ticking to May 2020.

One thing is clear: London needs good planning to tackle the housing crisis and ensure its long-term resilience, and the London Plan is the primary strategy for setting out how this should be delivered.

For more information get in touch with AECOM’s London Town Planning team.