Rising foreign investment and a shift in sellers’ expectations are playing a big part in re-strengthening Italy’s struggling property market, writes construction services director, Nicola Colella

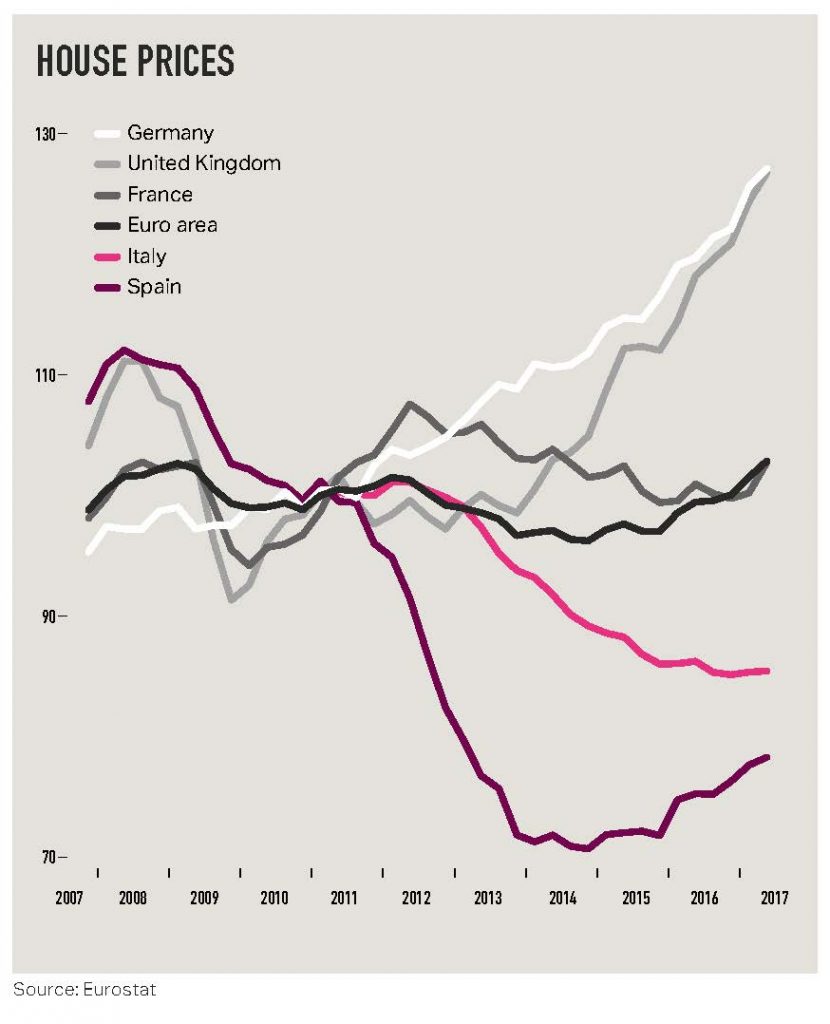

Italy’s property values have dropped significantly since the country’s real estate crisis began in 2008; average prices have fallen by almost 30 per cent after inflation, with suburban and less-appealing locations suffering even greater decline.

Italy’s property values have dropped significantly since the country’s real estate crisis began in 2008; average prices have fallen by almost 30 per cent after inflation, with suburban and less-appealing locations suffering even greater decline.

House prices in Italy fell 1.2 per cent year-on-year in the first quarter of 2016, showing a slight increase during the second half of 2016. Surprisingly, this is the only decrease among major EU countries, where overall house prices grew at an average of 4 per cent over the same period.

In Italy, the percentage of families owning their own home is fairly high, at 73 per cent, compared to 64 per cent in the UK and 52.6 per cent in Germany, with the construction sector’s contribution to employment still significant. The number of residential properties built in Italy each year has fallen by 85 per cent since 2005 however, reaching its lowest level in 2016, at just 41,000 units. Figures also show that there are around 100,000 fewer construction companies in operation and 600,000 job losses since 2008, with thousands of property-related businesses going bust, sending shockwaves through the banking sector.

Rising bad debts

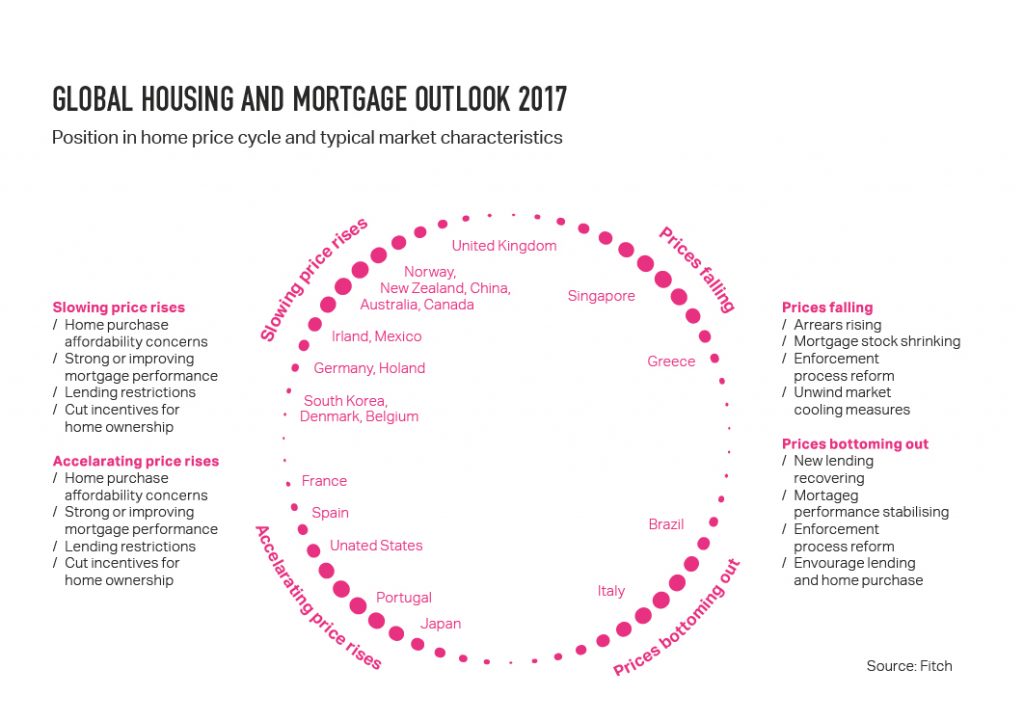

Real estate and construction companies account for more than 40 per cent of corporate bad debts, up from 24 in 2014 — a figure that is still rising. On top of this, approximately two thirds of bank loans in Italy are secured by personal guarantees or real estate collateral, so when prices nosedived, the debt coverage ratio was also negatively affected. So why do Italy’s house prices continue to fall? One explanation is that the fall seems to be delayed compared to other European countries.

A deferred drop?

Across the EU in 2017, Finland and Italy are expected to be the region’s laggards, with estimated growth of around just 1 per cent. Italy’s economy is failing to take off, remaining bogged-down by banking woes with the chances of reform suddenly stopping in 2016 due to the country’s constitutional referendum, with Premier Matteo Renzi resigning after conceding defeat.

Among the remaining major economies in the region, Spain is expected to outperform all others, with growth at around 2.5 per cent. Meanwhile Germany is expected to expand by 1.5 per cent, followed by France at 1.3 per cent.

The health of Italy’s national economy could be better. However, interest rates are at a record low. With business sentiment improving, small and medium manufacturing PMI staying strong and disposable income rising (at the end of 2015, the affordability index reached 11.3 per cent — 2.1 percentage points higher than 2014), we could reasonably expect more positive trends than those recorded by international agencies.

A reluctance to sell

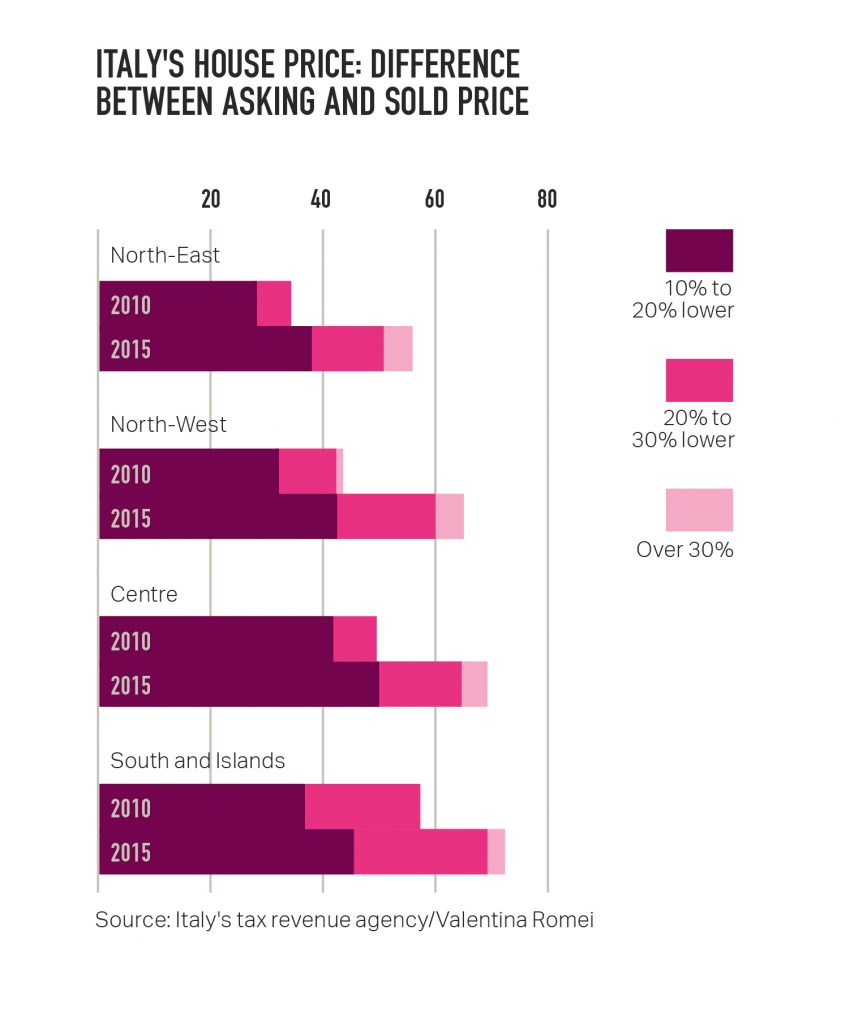

According to many across Italy’s housing industry, the main problem with the country’s real estate market is the large supply of unsold housing units: the Italian homeownerled market created a long-lasting reluctance to sell property at a discounted price when the crisis hit Italy in 2008.

Property owners were betting on a strong market recovery in the years ahead. However, the number of property transactions collapsed from 860,000 in 2006 to 403,000 in 2013 — the lowest volume in 30 years at a staggering 54 per cent. Over the same period, house prices dropped by 7 per cent — a far less significant drop than Spain’s 23 per cent.

More stable conditions

In 2014, sellers’ expectations suddenly changed as a result of more stable financial and political conditions and better economic measures. The average loan-to-value ratio increased to 60 per cent, with households needing to put down approximately €80,000 for a €230,000 apartment — down more than €15,000 compared to 2013.

Mortgage applications shot up by double digits in 2015, accompanied by a moderate upswing in credit applications from families. Applications for new and subrogated mortgages in 2016 increased by a little more than 13 per cent, consolidating the growth trend that started the year before.

A change in expectations

The number of residential properties exchanging hands increased by 10 per cent in the two years to the end of 2015 — 20 per cent higher than in Q1 and Q2 2016, but at lower than asking prices, reflecting a more relaxed attitude from sellers. At the end of 2016, almost two thirds of property sellers accepted 10 per cent less than the asking price. It is now common for sellers to slash prices by more than 20 per cent. Such drops did not happen even during the worst years of the housing market crisis, with the change in sellers’ expectations resulting in a delayed drop in Italian house prices, compared to other European countries.

Rising foreign investment

Rising foreign investment

In 2015 and 2016 the Italian real estate market grew at a steady pace, with €8.2 billion in total investment in 2015 mostly from foreign investment being led by the Middle East, Central Europe and Asia. Office and retail properties were at the top of investors’ lists, followed by hotels and industrial properties. Investment in the real estate industry in Q1 2016 reached €3.4 billion, about 9 per cent less than Q1 2015, where a single sale accounted for more than 10 per cent of the whole-year figures.

Big investments, high yields

The Italian market confirms to be extremely attractive for foreign investors who seek out core investments such as Rome’s Great Beauty portfolio and buildings located on Via Montenapoleone in Milan. Half of the money poured into the Italian market in 2015 went to Milan where, after decades of standing still, new architecture and hi-tech districts began to make sharp statements across the city skyline.

New buildings signed by Zaha Hadid, Arata Isozaki, César Pelli and Kohn Pedersen Fox have attracted high profile tenants, resulting in high yields; tenants in Milan’s city center pay up to €500 per square metre per year, with Rome’s central ‘A’ district fetching up to €400 per square metre.

The biggest investments are coming from open-end German funds, international property companies and sovereign funds, with office buildings accounting for 78 per cent of their transactions. In 2016, the Qatar Investment Authority bought 100 per cent of the Porta Nuova district development in a deal worth almost €1 billion.

Tech giants making their mark

Tech giants making their mark

In 2014 Google set up its headquarters in the 5,000 square metre building designed by William McDonough + Partners in the Isola district, while Microsoft Italy has recently set up Microsoft House within the impressive Swiss studio Herzog & De Meuron-designed building in Viale Pasubio. The company has invested €10 million in the fit out, designed by AECOM and DEGW, with the building housing not only Microsoft Italy’s HQ, but workshop, startup, conference and event spaces. Meanwhile, Amazon Italy will be relocating its business offices to via Monte Grappa. Once fully operational, the building will accommodate up to 1,100 staff.