Should cities be more like apps?

Ever since the advent of the smartphone, apps have been transformative. Whether allowing us to instantly communicate with millions, navigate unfamiliar cities, or request a private car, apps like Twitter, Google Maps and Uber now provide the digital infrastructure on which we increasingly rely. In the competitive market place of the App Store or Google Play, those apps which succeed typically share two interconnected traits: a compelling user interface coupled with a focus on problem solving functionality – and underpinned by a great deal of behind the scenes software engineering. Additionally, hardware and software resources are often shared with one another, from the use of cameras and microphones to GPS locations and personal contacts, synthesising digital environments that are greater than the sum of their parts. The results can be impactful, creating compelling experiences that keep us coming back for more. In many respects designing our physical environments is no different, or at least it shouldn’t be.

This designed environment, the Piazza Gae Aulenti in Milan, Italy, creates visual interest and attraction around passive ventilation measures for the sub-surface parking area below it.

Out of all the design professions that focus on our physical environment, landscape architecture holds a particularly unique position, being charged with reconfiguring areas of the Earth’s surface to form everything from regional parks and campuses, to city plazas. Given the strained condition of many of our planet’s environmental and social systems, this is an undertaking which clearly should not be taken lightly. Yet up until recent years landscape architecture has often been seen as little more than a means to beautify our surroundings – by both the profession and patrons alike. This attitude has roots in the Land Art movement of the 1970s and 80s, when areas of the Earth’s surface were seen as canvases on to which a designer-sculptor was free to do their will. These creations often showed little regard for the environmental systems into which they were inserted and had limited function other than as a piece of art. If these were apps, prospective users would be initially attracted by the interface graphics only to discover they had no function, and thus would be doomed to receive a series of 1 star ratings.

This designed environment along the waterfront at Blackpool, UK, welcomes people directly to the beach for the first time in over a century while using dune-shaped forms to protect the city from rising tides.

The virtual environments that apps create are often criticised for drawing people away from interacting with the physical world. Another way of looking at this is that the undeniable success of these digital infrastructures can be seen as an invaluable benchmark against which equally compelling, problem solving physical spaces can be designed. With the advent of climate change and rapid population growth, there are a host of issues that our built environments need to solve for, from sea level rise and storm water management, to healthy food provision, to passive heating and cooling. With the majority of people now living in cities, the interface with these elements is also key, not only creating engineered solutions but compelling places for people. Here we can learn from the most successful of apps, melding enticing user experiences with an underlying focus on solving for real world issues and desires, building physical infrastructure that forms unique urban places. These physical spaces should be thought of as apps in the truest sense, based on sound engineered principals and integrated into the urban fabric to form environments that are greater than the sum of their parts – ‘app-scapes’.

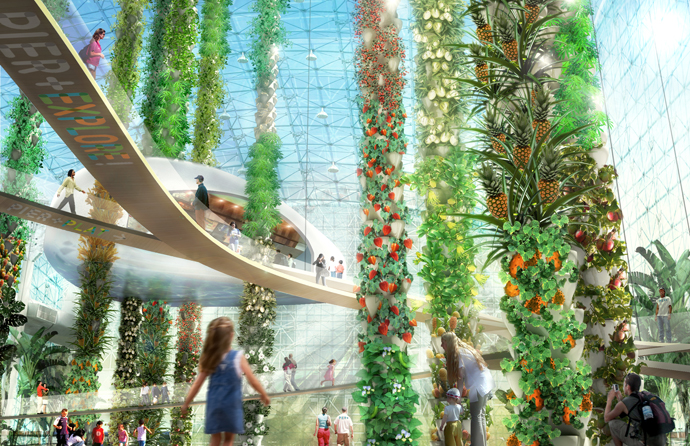

This theoretical environment makes urban food production (and consumption) the source of wonder and delight.

James Haig Streeter (james.haigstreeter@aecom.com) is a principal in AECOM’s global Landscape Architecture practice. He led the design of the Piazza Gae Aulenti, the development of the Urban Food Jungle concept, and was co-designer of the Blackpool Coastal Defenses.

James Haig Streeter (james.haigstreeter@aecom.com) is a principal in AECOM’s global Landscape Architecture practice. He led the design of the Piazza Gae Aulenti, the development of the Urban Food Jungle concept, and was co-designer of the Blackpool Coastal Defenses.